Experts have issued a new warning about the dangers of the terrifying “sloth fever” after the virus jumped from a pregnant woman to her unborn baby, causing a stillbirth.

The Oropouche virus, nicknamed “sloth fever”, caused alarm earlier this year after it spread outside its usual range in South America, to Spain, Italy, Germany and the United States.

The virus, named after the animal in which it was initially detected, has no vaccine or specific treatment.

It is known what causes headache, muscle aches, joint stiffness, nausea, chills, sensitivity to light and vomiting.

However, it can quickly cross the blood-brain barrier and enter the central nervous system, where it can cause meningitis and, in extreme cases, kill.

It is primarily transmitted through insect bites, but there is limited evidence that it can pass through. sex.

Until now, experts thought that only two cases of transmission of the virus between mother and child had been confirmed.

Now, in more alarming evidence of the virus’s potential to cause catastrophic consequences, doctors have reported another case that resulted in stillbirth.

The Oropouche virus, nicknamed “laziness fever”, caused alarm earlier this year after spreading from its usual range in South America and cases have been reported as far away as Spain, Italy, Germany and the United States .

Doctors documented the case in the northeastern Brazilian state of Ceará, where a 40-year-old woman who was 30 weeks pregnant was infected with the oropouche virus.

The unnamed woman developed fever, chills, muscle aches and a severe headache in July of this year.

Only three days later she began to experience light vaginal bleeding and a dark discharge from the area.

Her symptoms would continue for the next nine days and, although signs initially suggested the fetus was fine, subsequent scans confirmed that her baby had died during this period.

Molecular testing of samples taken from her confirmed that she had been infected with the oropouche virus.

Tests on the stillborn child found no developmental disorders, but analyzes revealed the presence of the virus in the brain, cerebrospinal fluid, lungs, liver, umbilical cord and placenta.

writing in the New England Journal of MedicineThe authors said: “These findings emphasize the risks of Oropouche virus infection during pregnancy and the need to consider this infection in pregnant women with fever or other suggestive symptoms who live in or visit regions where the virus is endemic or emerging.” .

It comes just months after more than a dozen cases of the oropouche virus were detected across Europe.

New warning issued about possible deadly consequences of ‘sloth fever’ after unborn baby dies

Although it is known as “sloth fever,” oropouche is not transmitted directly by the animals themselves, but by small biting insects, such as mosquitoes, which can transmit sloth disease to other animals, including people.

Oropouche symptoms usually begin four to eight days after the bite.

Although life-threatening, fatal outcomes are extremely rare and recovery from the disease is common. In most cases, symptoms disappear within four days of onset.

Experts are still studying the exact impact of Oropouche on pregnancy. However, cases of miscarriage and an increased risk of a birth defect called microcephaly, which causes babies to have a very small head, have already been documented.

The virus belongs to the same family of pathogens as Zika, which is known to increase the risk of miscarriages and birth defects.

Oropouche cases remain low in Europe and all cases are believed to be linked to people traveling to affected areas and becoming ill upon their return.

However, between January and mid-July of this year, more than 8,000 cases have been registered in Brazil, Bolivia, Peru, Colombia and Cuba.

Due to the high number of cases, European health officials warned citizens traveling or residing in epidemic areas about a moderate risk of infection.

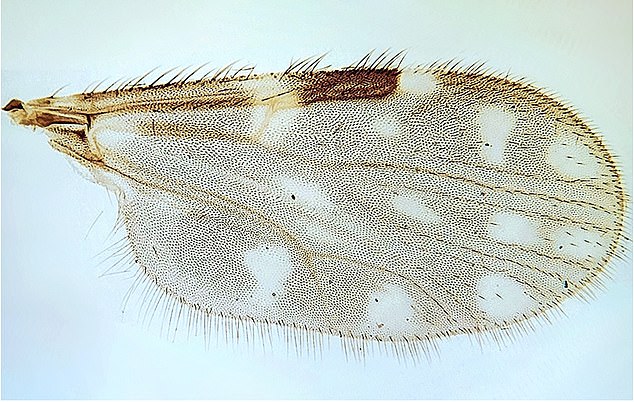

The pattern of spots on the insect’s wings is a characteristic of mosquitoes and mosquitoes that carry the “sloth virus”

They advised those in affected areas to wear insect repellent, long-sleeved shirts and long pants to reduce the risk of being bitten.

Experts say oropouche is unlikely to “take hold” in countries with colder climates like Britain, but could become a problem for those traveling abroad.

Analysis of the current strain of oropouche suggests it has grown to become more efficient at infecting people and this could be behind the rise in cases and in areas where it has not been seen before.

Climate change is thought to contribute to the increase, as habitat destruction has increased interaction between humans and animals that potentially transmit the disease.

Oropouche was first seen in an area of the same name in Trinidad and Tobago, back in 1955.

Five years later, during road construction, a sloth was tested and found to be carrying the bag of gold that gave rise to its nickname.

However, several animals, not just sloths, are believed to be potential carriers of the virus.

Most previous outbreaks of the virus, of which there have been more than 30, have been centered in the Amazon basin.