ITV’s new thriller Red Eye has been criticized by viewers for being full of “plot holes” and being “implausible”.

The new six-part drama starring Richard Armitage began on Sunday night, but while some admitted it was “gripping”, many thought the plot left a lot to be desired.

The plot follows Dr. Matthew Nolan (Richard), a British surgeon who is arrested at Heathrow Airport after returning from a medical conference in China, where he nearly died in a car accident in Beijing before boarding his flight.

Chinese authorities are insisting on his immediate arrest and extradition because they say a female passenger died in his car, but he insists he was alone.

London detective Hana Li (Jing) is assigned to escort Dr. Nolan back to Beijing on a red-eye flight, but when passengers start dying on board, she realizes that Nolan’s life is in danger and that There is an international conspiracy afoot.

Viewers have criticized the “ridiculous plot holes” in ITV’s new six-part thriller Red Eye. Here, Dr. Matthew Nolan (Richard Armitage) enjoys a G&T on a flight, despite being suspected of murder.

It soon becomes clear that the people on board are not what they seem and the duo begin to work together to solve the mystery.

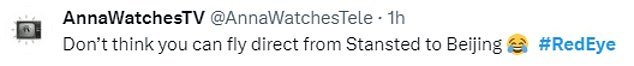

Eagle-eyed viewers were quick to point out inconsistencies in the show, even calling it “ridiculous.”

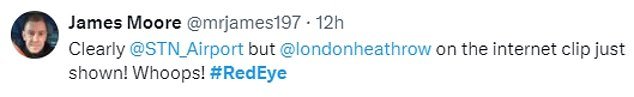

Some noted that while the airport chase scene in the first episode should take place at London Heathrow, it was actually filmed at Stansted.

Onlookers said: “I don’t think you can fly directly from Stansted to Beijing.”

‘Clearly @STN_Airport but @londonheathrow in the internet clip just shown! Oh!’

Others took issue with the show’s legal stories, pointing out ‘loopholes’: ‘Enjoying #RedEye, but completely unrealistic. Extradition – in all cases – requires that a judge (at least) approve it, there is an appeal process – and it can take a long, long time’;

“The lack of legal credibility in the #RedEye plot makes it difficult to enjoy.”

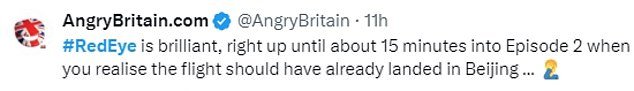

A third inconsistency seemed to be how much time the characters actually spent on the plane, because most of the six-episode show takes place in the air.

A night flight should be a short-haul flight that takes off in the afternoon and arrives in the morning, but the plane takes off during the day.

While the airport chase scene in the first episode is meant to take place at London Heathrow, the show is actually filmed at Stansted.

Another inconsistency seemed to be how much time the characters actually spent on the plane.

Viewers said: ‘How exactly is the plane 8 hours away when we had just seen on screen that it was 7 hours away from Beijing?’

‘Last time I checked Beijing is about 10 hours from London (flight time). That means they are about 3 or 4 hours away! Every minute that passes is sillier!’;

“#RedEye is brilliant, until 15 minutes into episode 2 when you realize the flight should have already landed in Beijing.”

Others noted that a “red-eye” flight is supposed to be a short-haul flight that takes off in the afternoon and arrives in the morning, leaving passengers drowsy and red-eyed from lack of sleep.

However, the flight on the schedule clearly takes off while it is still light, and would give passengers plenty of time to sleep during the more than 10-hour trip.

And even though Nolan is a suspected murderer, they give him a seat in business class and allow him to order a double gin and tonic.

‘Another double?’ So the “killer” is allowed to fuck on the flight? joked one viewer.

‘A deportee on a flight drinking double gin and tonics in handcuffs. It wouldn’t happen’;

Eagle-eyed viewers were quick to point out inconsistencies in the show and even called it “ridiculous.”

At least you will travel in business class. It could be worse, huh.’

However, others praised the show: ‘I didn’t sleep until two in the morning, but I saw even the most magnificent ending. Intense, exciting and captivating’;

“The best I’ve seen in a long time”.

During an appearance on BBC Breakfast about his role on the show, Armitage admitted that he had only seen the first episode because he found it “difficult” to watch the show again.

While he is an experienced long-haul traveler and usually writes while on the plane, Armitage, 52, admitted that filming the show had made him think twice before.

He said: ‘The first flight I did after filming, I started looking around the plane. There is a part of this plane that I didn’t know existed, like the crew quarters below. And our program becomes a kind of morgue.’

London detective Hana Li (Jing) is assigned the task of escorting Dr. Nolan back to Beijing immediately on a red-eye flight.

The Daily Mail review gave the show four stars and said that while it may be “silly”, it “moves along quickly”.

Nolan is put in danger on the show when he is served a vegan meal laced with poison; However, a poor passenger accidentally eats the food intended for him.

Elsewhere in the thriller, Lesley Sharp stars alongside MI5 CEO Madeline Delaney, while Jenna Moore is a reporter.

Viewers compared it to a detective novel and even to the famous aviation comedy Airplane (1980).

Armitage seems like the right man for the lead role in a thriller, as he also starred in Netflix’s Harlan Coben mysteries Fool Me Once and The Stranger.

FEMAIL has contacted ITV for comment.