At 64, Judy King was sitting on a psychologist’s couch, her life on the verge of a revelation.

Memories she had long buried erupted like a landslide, leaving her breathless and crying.

For decades, the Sydney-born woman had kept the pain inflicted by those who loved her most under lock and key. But when the walls of repression collapsed, a harrowing panorama emerged, one that could no longer be ignored.

Piece by piece, Judy began to piece together her fractured past, tracing her journey back to when she left Australia many years earlier. What emerged was a lifetime of traumas that would break her for the most part: a childhood marred by her father’s abuse, an adolescence violated by her uncle’s rape, and the anguish of giving her baby up for adoption at just 19 years old. .

“Not only did I feel worthless: I believed I was at the bottom of the scale of humanity,” Judy shares. “I was a prisoner of my own inner chaos, completely disconnected from the world and how others saw me.”

“When I was a child I was afraid of everything,” she continues. “Self-confidence was not only low, it was non-existent.”

Judy, now 82 years old and living in Mallorca, Spain, radiates a strength forged through decades of healing. Although she misses her homeland, she is finally ready to share her story: a testimony of resilience, survival and recovery of self.

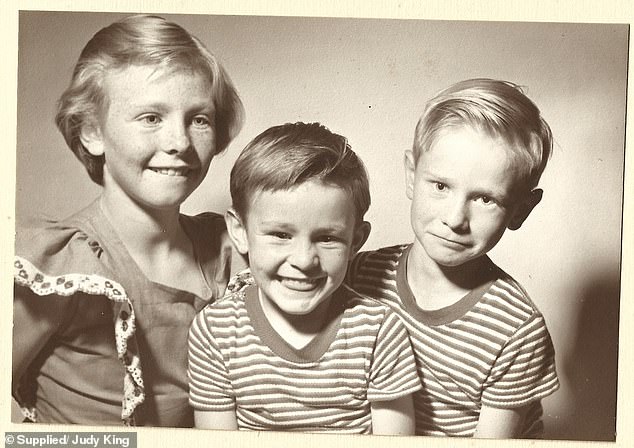

Abused by her father as a child, raped by her uncle as a teenager, and then having to say goodbye to her baby at age 19 would be enough to crush anyone. That’s what happened to Judy King (pictured left with her two brothers in an undated childhood photo)

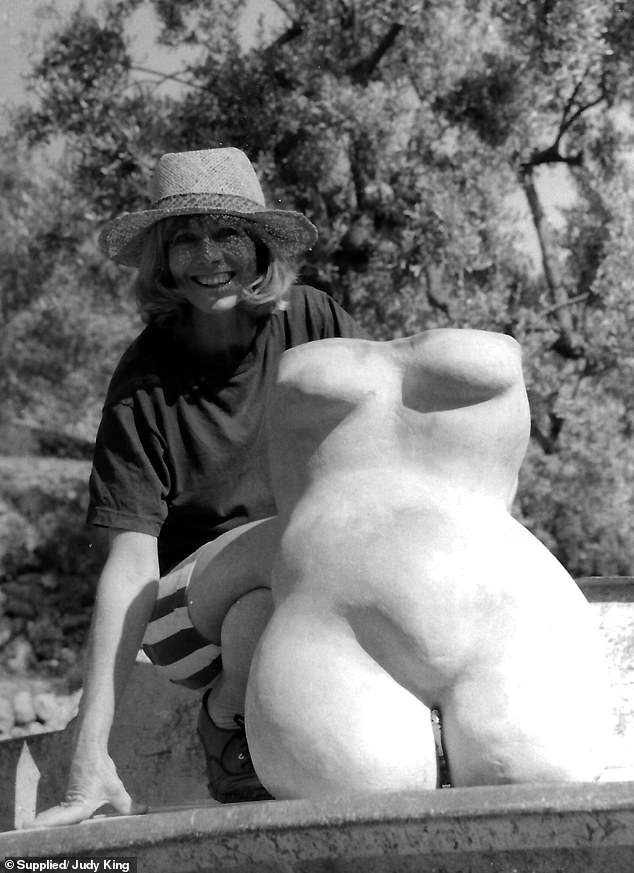

“I thought I was on the lowest rung of the human ladder,” says Judy (pictured in her mid-20s, after giving up her daughter for adoption).

As a child, Judy’s life was marked by isolation and sacrifice. While her two younger brothers were sent to boarding school, Judy was left behind, “sacrificed” to stay home with her parents.

Her father, a salesman, was often absent, leaving Judy at the mercy of her mother, a woman she describes as volatile and incapable.

“When Dad was away, my mother relied on me; she was pretty desperate, but when he came home, she didn’t want anything to do with me,” Judy explains.

‘She was a strange woman, very hot and cold. Looking back, she was probably a psychopath. She was never a good mother and was incredibly lazy.

Judy remembers her mother spending days resting in her bed, adorned with expensive pearls, but completely indifferent to the world around her. “She would call me from another room to go get a pack of cigarettes from her bedside table, something she could have easily done herself.” That’s how lazy she was,” says Judy.

Both of Judy’s parents were abusive and neglectful. They never picked her up from school or attended assemblies, treating her as if she were invisible.

His mother, whom he describes as a “living embarrassment,” always seemed to need help with the simplest tasks. However, despite her mother’s erratic behavior, Judy still felt a deep feeling of love and the need to protect her.

Growing up on Sydney’s north shore, Judy endured horrific abuse at the hands of her father, while her mother turned a blind eye. To add to the emotional damage, her parents gave her cruel labels.

You were always a terrible flirt. Everyone said it. You were a classifiable criminal. Everyone thought the same thing: your school, your grandmother, the whole family!’ they would mock.

Judy had no idea what words like “provocative” or “flirty” even meant as a child, but her accusations persisted, leaving her to grapple with misplaced guilt and shame.

Judy grew up on Sydney’s north shore, where her father abused her and her mother turned a blind eye. Judy was told she was ‘provocative’ and ‘flirtatious’ as a child

Judy’s life took a distressing turn when she was sent to live with her uncles in Maroubra. It was there that something absolutely baffling happened that would take years (decades) to properly explain.

She became convinced that she had accidentally set fire to the kitchen, a belief which her relatives denied, insisting that no such event had occurred and dismissing her as “crazy”.

Years later, a therapy-induced flashback revealed the truth behind his confusion. Her uncle had taken her to the basement of his Newtown pub, where he assaulted her on an old iron bed, surrounded by beer barrels. The imagined fire was his mind’s way of processing trauma: his way of interpreting blood and pain that he couldn’t understand at the time. Although the fire never happened, its emotional weight burned within her for decades.

At 17, Judy left Maroubra and sought refuge in a nursing home on Coogee Beach. That period of time was so tense that he still doesn’t quite know how he ended up there. Pieces are still missing to this day.

But the new life situation did not bring respite. As her terrible teenage years came to an end, she became involved with an abusive and controlling boyfriend. He got her pregnant, another catastrophe.

“I was so naive that I didn’t understand how I could get pregnant by such a terrible person,” she says. “I went to the priest to confess and trusted him, even though I had committed every sin in the book.”

The priest put her in touch with a kind-hearted nun who became a lifeline in her darkest moment. “She was the first person who admired me and defended me,” Judy remembers.

The nun helped Judy deal with her pregnancy in secret. Together, they decided that Judy would give her baby up for adoption and, to protect her identity, she adopted a false name: Catherine Johnson.

This new identity, although temporary, gave Judy a sense of escape and empowerment.

“It was exciting and exciting,” he says. “I worked in daycare, I got up at 6 in the morning to take care of the children and change diapers before going to the office.”

Judy, now 82, began unraveling her past after consulting a psychologist at age 64. He has been seeing a therapist for the past 20 years.

In the midst of the chaos of her life, Judy finally found a fleeting sense of stability and purpose.

After giving birth to her baby, Judy only had a brief moment to bond with her. If I had the chance, I would have called her Rebecca Lea.

At the age of 20, Judy was working in real estate and property development in Paddington, finding solace in restoring old houses. Work became a powerful outlet for her.

“The desire to repair and restore old houses that had fallen into ruin was an external metaphor for what I longed to happen inside of me,” he reflects.

Despite the emotional weight she carried, Judy dedicated herself fully to her work. ‘I worked hard seven days a week but I had a wonderful time. The houses in Paddington are beautiful and I still love them to this day. I still know the area like the back of my hand.

In 1968, Judy’s father died from an infection that caused his throat to close. He was rushed to Liverpool Hospital but died shortly after arrival.

A year later, at age 27, Judy left Australia with her future husband to explore the world. Over the years he lived in London, Kuala Lumpur, Sri Lanka and finally Mallorca.

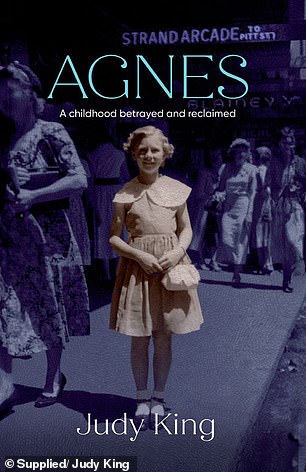

Judy put her story into words and published a book titled ‘Agnes, a Childhood Betrayed and Recovered’.

Their marriage, like much of their life, was marked by pain. It lasted seven years and was abusive. Moving to Spain wasn’t Judy’s dream, it was her ex-husband’s, but she has since come to accept it.

‘Relationships were never my strong point. “When you have an abusive childhood, you gravitate toward toxic people,” Judy says.

‘You can’t control it; It’s like I’m going back to my parents in a way. You gravitate towards what you know and what is familiar.’

Judy never had the chance to meet her daughter.

After her mother died, Judy’s brother discovered a box of letters addressed to her, letters she didn’t know existed. By then, it was too late to respond.

“My brother called me saying he had found these old letters addressed to me, but I had no idea who they were and I still didn’t know I had a daughter,” Judy says.

‘I didn’t know what he was talking about until I saw the cards myself. I tried my best to find her in 2006 but I couldn’t, it was impossible. To this day I have no information about her.

Although she has made peace with the situation, Judy admits that it still weighs on her. ‘It’s always in the back of my mind. I had no choice but to give it up when I was younger because I had no money.

Today, Judy focuses on herself, a form of self-care she never knew growing up. He no longer resents his parents. In fact, she has no feelings for them.

Despite the painful memories associated with Sydney, Judy has managed to reclaim the city in her own way. Seventeen years ago, she returned to present her book Agnes: A Childhood Betrayed and Claimed.

‘I dream of Potts Point. I would live in Australia again if I could. “Sydney is one of the most beautiful places to live and I miss it,” he says.