As an 18-year-old trainee nurse, I was working on a pediatric ward during a whooping cough epidemic. Parents were only allowed to visit two hours a day: from 2 to 3 p.m. in the afternoon and from 6 to 7 p.m. at night.

One morning, at 4am (I was at night), I was in the ward’s office, where a junior doctor was talking on the phone to the sister from the ward opposite, a children’s surgery ward.

“There was a girl on the landing, about four years old, looking for her mother,” he was telling her. ‘She came back through your door, do you have her?’

I left the office momentarily and when I returned I found him looking at the receiver. He looked at me: “They don’t have a girl in that room,” she said. “Only babies.”

He looked like he had just seen a ghost. She really she had done it.

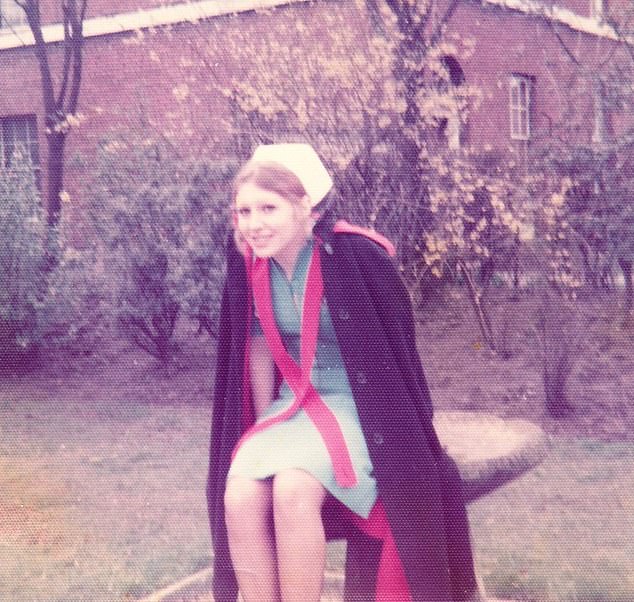

Nadine Dorries was a trainee nurse when one of her ward mates thought he had seen the ghost of a girl.

I was reminded of this disconcerting event while reading about Julie McFadden’s experiences in the Mail on Saturday and The Mail on Sunday. As a palliative care nurse, she has been at the bedside of numerous dying patients and has seen and heard many things she cannot explain, from the presence of a comforting “angel” to the calming visions people experience in their final hours. .

In my nursing days I frequently witnessed the unexpected, the spiritual or simply the ghostly. I have held the hand of more people than I can remember when they took their last breath and it was a great privilege to do so.

I have sat in dark rooms, late at night, knowing that the end was imminent. I turned off the night lights and closed the doors to keep out the noise in the living room and then pulled a chair up to the bed. I kissed a forehead and whispered to someone that they weren’t alone and that I wouldn’t leave them. In those moments I stopped being a nurse and that was when things could happen… things that cannot be seen and are difficult to explain. It would start as a sensation, as if someone had entered the room, but no one had.

A sudden smile on the face of the dying person or a whispered word, often a name, and then the awareness of a presence that fades and takes with it my patient’s life force.

I have also faced similar situations in my personal life. In her last hours, my mother-in-law, who was being treated for a brain tumor, sat on the bed while I fed her meatloaf. We laughed and talked and I believed the surgery had worked. I didn’t recognize the pity in the nurse’s eyes. I stupidly did not recognize the phenomenon for what it was: terminal lucidity, the sudden rise or recovery that occurs in a small number of patients and lasts long enough to say the unsaid.

My mother-in-law and I told each other how much we loved each other and how important she was to all of us, especially her grandchildren. It lasted an hour and was one of the most important hours of my life.

And I will always remember my patient Grace. Her four daughters sat vigil around her bed as she lay dying at home. One day, she touched my wrist and I bowed my head to listen to her. “Get rid of them,” she said.

I was in my twenties and my daughters were twice my age. They had been arguing the entire time they were in the room and it occurred to me that the poor woman just wanted to die in peace. I felt sorry for her, so I gathered my courage and suggested that everyone get off her. They accepted meekly. I later heard from the night nurse that Grace had left peacefully in the early hours while her four daughters were asleep.

Julie McFadden says her experiences have convinced her that there is nothing to fear about death. That’s certainly what my 97-year-old uncle believed. He was a wonderful man, a devout Catholic who, long before he died, told me that dying was the thing he feared the least in life.

Two months ago I attended his funeral on the west coast of Ireland. The weather was fierce as always. Cold and gray, the rain lashed down with the force of the stair bars.

As we hurried into the church (both to escape the pouring rain and any desire to be punctual), I already dreaded the walk back to the cemetery on a hill overlooking Croagh Patrick, a pilgrimage mountain where It is said that Saint Patrick spent 40 days fasting at the summit.

Unlike many members of my family living in Ireland, I haven’t yet grown a pair of gills and find that special Irish combination of wind and rain daunting, to say the least.

Nadine with her late husband Paul. Just after her death, a doe ran into the family’s garden, all of them named Doe.

The service was due to begin at noon sharp, and my uncle was the first to arrive, the candles around his coffin piercing the gloom. His wish had been granted. He would spend his last night on Earth, alone with God, in the church where he had worshiped almost every day of his life.

The choir sang to us. The two officiating priests took their places at the head of the coffin. At 11:59 the choir fell silent, the bell rang the first stroke of twelve and… suddenly, the gloom dissipated when a ray of sunlight passed through the stained glass window and fell in a column of color to land on the coffin. of oak that glowed orange with flames.

The congregation gasped and one of the priests smiled. “There you go,” he said as he pointed to the beam of light. “That’s his first-class ticket to heaven sent straight from God Himself, right there.”

For me there are so many things about death that we cannot explain or understand, but seeing is believing, then I believe that death is not the end.

We need not rush or embrace it, but, as my uncle advised me, let us not fear it and take comfort in the assurance, imagined or not, that those we have lost seem to want to move on.

I have written about my husband Paul’s death before in this column, but never about the moment of his death.

He was a strong-willed man who didn’t want to leave us any more than we wanted him to leave. Our bedroom faced south, with a balcony overlooking the garden, and we had brought the hospice bed up to the doors. It was a warm June day when he left us. At his last moment, he sat up very straight. In a few moments, the room went dark and the heavens opened.

We’ve had a family nickname for a long time: we’re all called Doe. Hello Doe. Fly safely, Doe. See you later, Doe.

A few seconds after taking her last breath, a doe ran into the garden and looked up at the balcony. A sight we have never seen before or since.