Ironically, the first time I received clear sex education, it was strange.

I was 19 years old and little by little I fell in love with Dassa, a young woman who lived in a home as protected as mine.

We had never seen television. We didn’t listen to American popular music. We read Jewish novels from the Judaica store.

And we didn’t know what to think about the way we craved each other, about the way I’d ask him to sneak into my room at night, where we’d throw our clothes on the side of my bed and merge, skin to skin. fur.

After several months of feeling completely out of control, we both thought we needed a little more information.

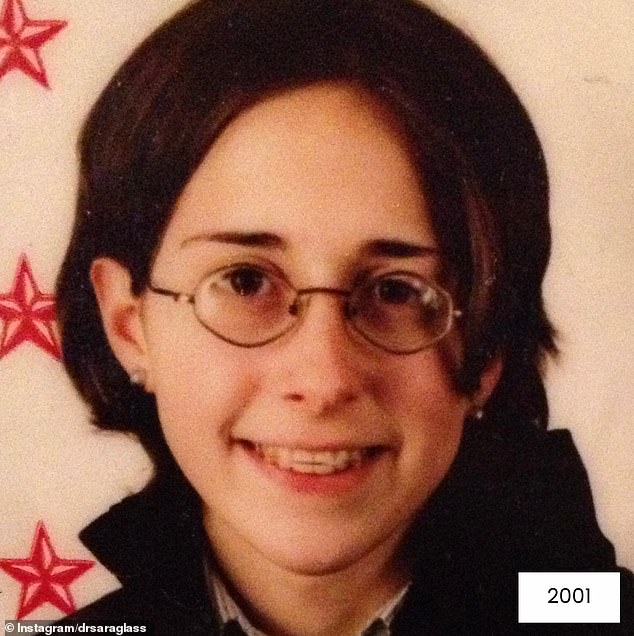

Sara 16 years old. Three years later she was falling in love with another woman.

At 19, Sara received her first sexual education, which consisted of a tube of toothpaste and a pencil-shaped toy. She is pictured wearing her first full wig.

Sara on her wedding day: ‘My husband was forbidden to look at my private parts or put his mouth near them’

Dassa made an anonymous call to a rabbi and asked him a question: Were two women allowed intimate physical contact?

The rabbi said that for men it would have been a very bad sin, but for women it was simply disgusting. Still, he noted, if we penetrated each other with an object, ‘like a cucumber or something,’ we would cross the line into actual sin.

We had received a nisayon, said the rabbi, a test from God. He offered Dassa a blessing for strength to resist him.

As I write these words, sitting in Manhattan’s West Village, I am aware of how naïve I was back then.

At 39 years old, I’m still confused about the rabbi’s choice of words, but at least I can laugh about it.

At the time, however, I didn’t understand the humor of the situation. I was determined to pass God’s test, so I agreed to meet Yossi, the young man my family had examined for me.

He showed up to our first date wearing a dark suit, a black fedora, and soft blue eyes. We sat across from each other in a hotel lobby and talked about how we would raise godly children.

Three weeks later, we were engaged to be married and my second round of sex education began.

I began attending ‘bridal classes’ with a woman who taught me about Jewish laws regarding marital intimacy. I had to avoid touching my husband for two weeks of every month, during my period and the seven days after.

I had to wipe a white cloth inside my vagina for each of those seven days and then hold it up to the light to make sure it was clean and blood-free.

Then, I had to immerse myself in a ritual pool called mikvahwhile a religious woman kept watch to make sure my entire naked body was submerged in the water, after which she could declare me “pure” and send me home to my husband.

All of that seemed fine to me. She was willing to do whatever God wanted, to perform the holy act of intimacy.

I found out that the event would take place in complete darkness. It was going to happen in something called the “missionary position.”

My husband was forbidden to look at my private parts or bring his mouth close to them.

As soon as the act was completed that first night, my husband was to retire to his own bed, across the room from mine. He was to put a scarf over my hair again and immediately put on a long-sleeved nightgown, so that he wouldn’t see any of my skin.

He would not be allowed to touch me, kiss me, hold my hand, or even pass me something as innocuous as table salt, because the briefest touch of our skin could cause him to sin.

Those restrictions would be implemented during each of my “impure” periods of time, whenever I experienced vaginal bleeding, whether from losing my virginity or from my regular period.

However, what “intimacy” meant was less clear. I didn’t know exactly what that act would entail until days before my wedding.

‘Forward! Ready for the wedding? Mrs. Levenstein led me past a living room filled with toys and into a study filled with leather-bound volumes.

On the metal folding table between us, I saw what appeared to be an empty toothpaste tube and a flexible pencil-shaped toy.

Sara, 25, recently divorced, rebelliously pulled some natural hair over the hairline of her wig.

Sara, 31, married to a man (again), models what she describes as a “Modern Orthodox Jewish spark plug wig.”

It was ten years and many painful experiences later when she decided that being a saint no longer worked, and if that meant she was also a pagan, so be it.

“When a man and a woman come together, it is the most sacred act in the world.”

I nodded, listening attentively. She knew it.

He picked up the tube of toothpaste and I noticed little stickers stuck to the white cap. They formed the shape of a face.

“This is the woman’s body.” She folded it and left it on the table.

He picked up the flexible toy. “This,” she said with a solemn intonation, “is the man.” ‘His body enters the woman.’

I felt my stomach flip. I saw her take a small balloon out of a box.

“This is a jerk, but today it will be yours.” always.’ He used the Hebrew word for organ, as if to sanctify the euphemism.

She demonstrated how the long pole at the end of the shower was the part of a man’s body, between his legs. She pointed it toward the floor and then toward the ceiling.

“When he gets closer to you, he’ll get bigger and appear, and that’s how he’ll get to your private part.”

She pursed her lips to demonstrate what a vagina was like down there.

That was what he would have to do with Yossi, the man he barely knew.

I questioned this. Could no one have told me before? I didn’t want it close to my body, much less inside.

I returned to the streets of Brooklyn, Mrs. Levenstein’s voice echoing behind me: ‘Call me the next morning if you have any questions!’

Mrs. Levenstein guided me through my seemingly endless list of questions during the early days of my marriage.

She helped me figure out how to maneuver my body and his so we could consummate our marriage. She gave me the phone number of a birth coach when I became pregnant with my first child.

Sara eventually moved with her children from the community to Manhattan, where they have lived for the past seven years (pictured with her daughter Jordan).

She listened when I called her with questions about my relationship after the distressing birth of my second child and referred me to the best marriage counselor she could find.

Then my questions became too big for her, too big for me, too big altogether. She asked me where the love was, the feeling they said she would have for my husband. I was afraid to ask about my incessant thoughts about women, my constant desires for a soft face brushing mine.

I obtained special rabbinic permission to leave the community one day a week and attend classes at the Rutgers University School of Social Work.

There, on the secular university campus, I learned things that I was sure must be lies. My teachers seemed to believe that the sacred act of intimacy was something much more profane, something that could happen in nightclubs and between single people, and, most surprising of all, they believed it could be pleasurable.

They reflected on the mistreatment of homosexual men in our society and advocated for free and equal love. I thought they were pagans.

It was ten years and many painful experiences later when I decided that being holy no longer worked, and if that meant I was also a pagan, so be it. I had finished sacrificing my body for God, I had finished serving as a vessel for his will.

I ventured outside my community and found the gayest place my rudimentary Google skills could take me: the Stonewall Inn.

I sat on a bar stool, turned on my leather and lace covered shoulders, and ordered a drink. I sipped and met the eyes of women with short barber haircuts, women in baggy cargo pants and bare midriffs, women who smiled at me, welcomed me, and challenged me.

‘You want to dance?’ A woman with caramel skin leaned close to my ear.

I let him get up as if it were a normal Saturday night for me, as if his hand around my waist was the most natural thing in the world. I felt her hips against mine, and her gentle movements made my legs seem almost elegant as I walked with hers.

Surrounded by rainbow flags and the sound of Lady Gaga, we danced.

It felt like heaven.

Once I knew, truly knew, that I was gay, I was free. I moved with my children from my Jewish community enclave in Brooklyn’s Borough Park and we moved to Manhattan, where we have lived for the past seven years.

Now I can kiss women on city streets and hang rainbow flags on my refrigerator. I get to fly across the country and speak to audiences looking for ways to access their own inner truths.

I hope that by sharing my story I can offer a little hard-won wisdom: the answers are already within us.

The most important sex education we will ever receive is about our own bodies. Deep down, we already know how we feel in our relationships, how we react to various smells, sounds, and requests. It’s up to us to tune in, listen to what our body is saying, and believe in ourselves.

Sara Glass, PhD, LCSW, is a New York-based therapist, writer, and speaker who helps members of the queer community and people who have survived trauma live bold, honest, and proud lives. The first memories of her, Kissing girls on Shabbat, is available wherever books are sold. Find out more on Instagram @drsaraglass