Susan Weiss Liebman spent years searching for the tiny genetic mutation that lurked in her family’s DNA and caused unexplained abrupt deaths for generations.

Her research, detailed in her new book The seamstress mirror, began with the sudden – and inexplicable – death of her niece Karen.

Dr. Susan Weiss Leibman’s book is at once a memoir, an exploration of genomics, and a mystery, as she tries to uncover the cause of untimely deaths that plague her family.

Karen was 36, otherwise healthy and pregnant when she collapsed in a Brooklyn restaurant in 2008 as a result of dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM), a condition that causes the heart to become weak and enlarged cannot pump blood effective.

This was the same condition that Karen’s mother Diane had been dealing with for years. It was genetic, but no one would learn that for almost a decade.

Dr. Liebman writes, “This meant that Diane’s disease was genetic and not a complication of a viral infection, as doctors previously believed. Instead, Diane passed on a deadly gene to Karen.”

“We had to find the mutation before God’s cruel game of Russian roulette provoked even more members of the family.”

The tragedy, nearly a year after her father’s sudden fatal heart attack at age 66, prompted the 78-year-old to use her expertise as a geneticist to find an answer. She immersed herself in research and corresponded with experts in the field about the latest discoveries in the variations of human DNA that make a person who he or she is.

Dr. Liebman soon discovered that many members of her family had inherited a potentially fatal gene mutation responsible for making a protein crucial for maintaining the function and structure of muscle cells, including those that make up the heart.

Dr. Susan Weiss Liebman’s new book, The Dressmaker’s Mirror, is both a memoir and a genetic exploration, following generations of her family marked by sudden deaths

When Dr. Liebman was a child, she heard the story of the untimely death of her father’s brother, Eugene.

Eugene was only four years old when he was crushed by a falling mirror in 1916.

Relatives tried to take the mirror away from him, but it was too late and the story haunted Dr. Liebman for decades — until she learned it was a lie.

The four-year-old’s death certificate said nothing about an accident, a mirror or being crushed. In reality, the child had died of congestive heart failure after a five-day hospital stay.

The death was not a freak accident. He had inherited a killer gene that later affected Dr.’s grandmother, father and niece, among others. Liebman in her family tree.

Her father never knew the family’s grim secret, and she did not learn the truth until she had been an experienced geneticist for thirty years.

She said: ‘I have always considered genetics in terms of my career. I studied it as an undergraduate at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) and as a graduate student and postdoctoral researcher at Harvard and the University of Rochester.

“I understood that genetics determined my eye and hair color, my dexterity, and other traits, but I never thought it would have a significant impact on my real life. Now that’s all changed.’

Dr. Liebman’s niece Karen is pictured with her husband Andrew. The couple show off Karen’s baby bump just one day before her bizarre fatal heart attack

The hunt for the perpetrator took years and several rounds of DNA testing of Dr. Liebman and her sister Diane.

On every test they came out with no answers. There were no red flags or clues.

It was only when Diane died of heart failure in 2016 at the age of 73 that the pieces of the puzzle began to fall into place.

Genomics is constantly evolving. With advances in technology come more effective ways to examine genes in more detail and identify previously unknown genes or gene variants.

The sisters had provided blood samples before Diane’s death to geneticists now working at Northwestern University.

When Dr. Liebman contacted them and asked about the possible genetic link to her condition, Northwestern cardiologist Dr. Beth McNally broke the news that scientists had found a gene variation in Diane’s DNA that had previously never been linked to cardiomyopathy — but this could be the answer. now.

Dr. McNally said at the time of the discovery, Diane’s gene was the only gene linked to cardiomyopathy. But as the years passed and more and more reports linked the gene and the disease, “it becomes more likely that this could be a real connection.”

Dr. Liebman and her family are Jewish, a population at higher risk of developing the mutation that makes them more susceptible to fatal heart disease.

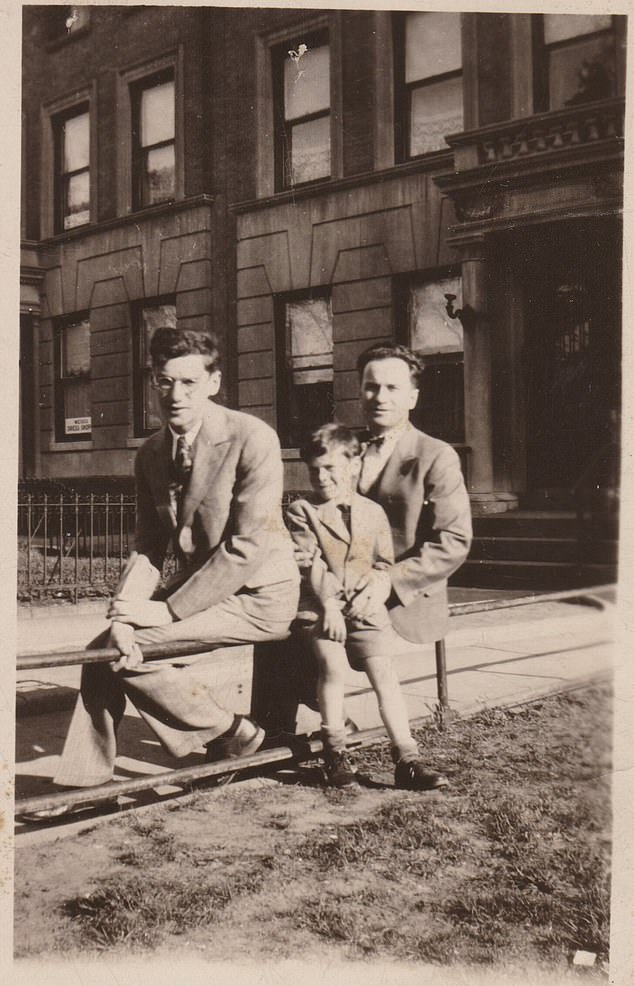

The photo shows Dr. Liebman’s father (left), who died of a heart attack at the age of 66, next to his brother Cyrus. Their father David sits on the far right. He died at the age of 41

‘I recently completed a little research which asked if the mutation in my family is a major cause of DCM among Ashkenazi Jews. Our results suggest so,” Dr. Liebman said.

The mutation changed a crucial part of the DNA. In some cases, Dr. Liebman explains, this can lead to a premature cessation of the production of a certain protein, which can contribute to potentially fatal heart diseases such as DCM.

When she heard about the defective gene, which she believes was passed down from her father’s side, she alerted everyone in her family.

She said: ‘I contacted all the cousins who had a 12 per cent and 6 per cent chance respectively of having the mutation.

‘Those who knew about my cousin Karen’s death were immediately interested. Those who did not know me and did not know Karen were sometimes skeptical about the relevance of my information and initially thought I might be part of a scam.”

Dr. Liebman also discovered that neither she nor her children were carriers of this deadly gene mutation, meaning they could no longer pass the gene on to future generations.

Finally, Dr. Liebman thought, they had an answer to the untimely deaths that had plagued her family for generations. Finally, they could know for sure whether future generations of their family would face a similar fate.

DCM does not have to be fatal. It can be managed with the right heart-healthy lifestyle factors, regular checkups, echocardiograms, and medications such as beta blockers.

Dr. Liebman is pictured with her husband Alan at their wedding reception in 1969

During her genetic exploration, Dr. Liebman had to reconcile her ancestral beliefs with the tragedies that had befallen them.

Dr. Michael Arad of Tel Aviv University, whose team had identified 23 mutations in the new defective gene, told her that the families he had seen with the mutation were of Ashkenazi Jewish descent, just like Dr. Liebman and her family, making it a Founder gene – a gene in the DNA of a small ancestral population that is passed on to a large number of descendants.

His research found that some people who died suddenly showed no signs of impending death on echocardiograms, the standard method for measuring the heart’s electrical activity.

All Ashkenazi Jews descend from a small population of fewer than 500 people in Eastern Europe, whose genetic origins were equally divided between Europe and the Levant, which today includes parts of Syria, Lebanon, Jordan, Israel, Palestine and parts of includes Turkey and Iraq.

“Remarkably,” she said, “the mutation in my family occurred in one in eight hundred Ashkenazi Jews, but was not present in the other ethnic populations.”

As the small population bred with each other, the faulty gene mutation spread among their offspring.

While he was once confused about why the family would lie about Eugene’s death more than a century ago, Dr. Liebman now understands that his mother hid the truth because she did not want her sons to be left out and without marriage prospects because the known risk of death. along their condition.

Dr. Liebman wrote, “Marion’s imaginary shattered mirror and the resulting broken shards of glass embody her observable fears for her family’s future.

Marion’s fear for her family proved prophetic, as untimely deaths plagued her descendants, including hers at age 59, her mother at age 47, her son at age 66, and later generations who suffered from heart-related conditions .

“Despite Marion’s premonition, she could do nothing.”

The lack of autopsies for Marion and her son obscured the genetic connection to DCM, which could have saved future lives with earlier awareness and treatment.

Dr. Liebman continued, “Grandma Marion modeled for us how to deal with loss by choosing life in response to heartbreak.

“What she couldn’t have known was that we would find out the cause of all the deaths, and that genetic testing and early treatment could end the family curse.”