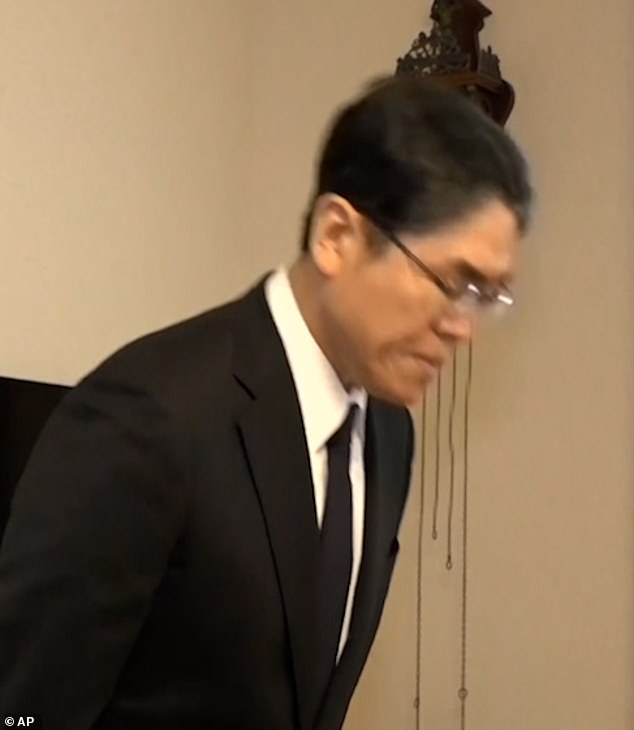

This is the moment a Japanese police chief solemnly bowed and apologized to a former boxer acquitted of murder after 50 years on death row.

Shizuoka Prefectural Police Chief Takayoshi Tsuda visited 88-year-old Iwao Hakamada at his home today to apologize after being acquitted of a mass murder charge.

Mr. Tsuda said, as he stood in front of Mr. Hakamada and bowed deeply: “We regret having caused him unspeakable anguish and mental burden for 58 years from the time of arrest until the acquittal was finalized.”

“We are very sorry,” he added, assuring that a “meticulous and appropriate investigation” will be carried out.

The Shizuoka District Court acquitted Mr. Hakamada after admitting that police and prosecutors had collaborated to fabricate and plant evidence against him.

Hakamada had initially pleaded not guilty to stabbing four people to death in 1966, but confessed after 264 hours of intense and often violent interrogation. He has since maintained that he was coerced and had no role in the murders.

Takayoshi Tsuda, left, offers an apology to former Japanese death row inmate Iwao Hakamada

Takayoshi Tsuda visited 88-year-old Iwao Hakamada at his home today

Iwao Hakamada, center, sits with his sister, right, as Tsuda arrives home to apologize.

Hakamada received the police chief with his sister (pictured right)

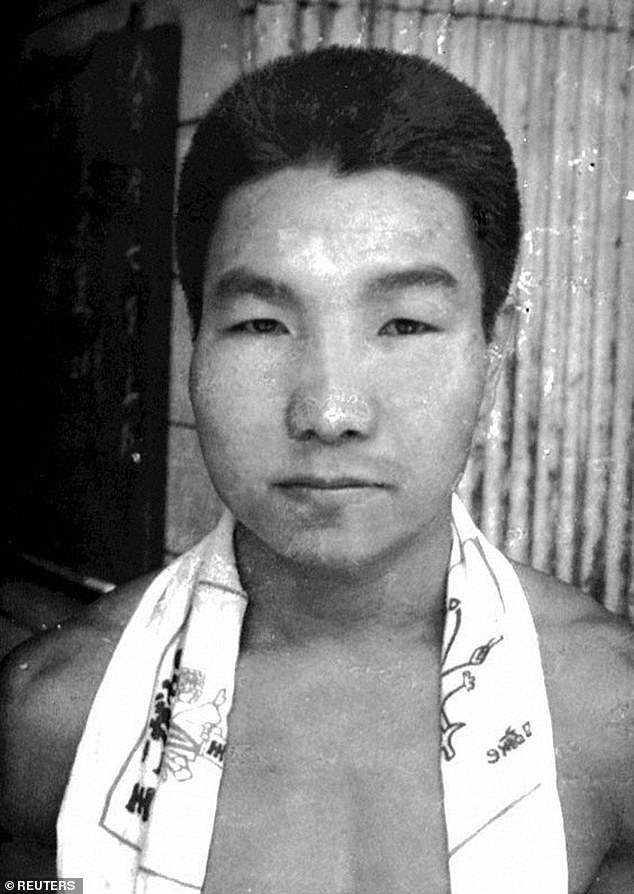

Iwao Hakamada when he was young. He spent most of his life in prison after being convicted of murdering four people in 1966. Hakamada maintained his innocence.

When the police chief entered the room, Hakamada silently stood up from his couch to greet him.

Mr. Hakamada, who has difficulty holding a conversation due to his mental condition after decades of confinement on death row, responded: “What it means to have authority… Once you have the power, you’re not supposed to. You should complain.”

Hakamada’s 91-year-old sister, who had supported her brother during the long process to clear his name and now lives with him, thanked the police chief for visiting them.

‘There’s no use complaining to him after all these years. “He was not involved in the case and came here only out of duty,” he later told reporters.

“But I still accepted his visit only because I wanted (my brother) to make a clear break with his past as a death row inmate.”

The sentence came more than half a century late for Hakamada, who has spent most of his life behind bars since his arrest in 1966.

The former boxer had been charged with mass murder in a highly publicized case called the “Hakamada Incident,” after four bodies were found in the rubble of a house fire in Shizuoka, west of Tokyo.

Mr. Hakamada’s employer, his wife and two children were found to have been stabbed to death in the house.

Authorities accused him of murdering the family, setting fire to the house and stealing 200,000 yen in cash.

Hakamada, an employee at the victim’s miso processing plant at the time, denied robbing and murdering the victims.

But he later confessed under what he said was duress and violent interrogation.

Hakamada said he “couldn’t do anything but crouch on the ground trying to avoid defecating” while in custody.

‘One of the interrogators put my thumb on an ink pad, drew it on a written confession record and ordered me: “Write your name here!” (while) he yelled at me, kicked me and twisted my arm.’

Two years after the incident, he was convicted of murder and arson and sentenced to death.

In the end, Hakamata was not executed due to Japan’s lengthy appeal and retrial process, and he languished in prison for more than 50 years until last month, when he was acquitted in a retrial.

Japan often notifies death row inmates of their execution just minutes beforehand, leaving Hakamata unsure of their fate for decades.

He holds the record of being the death row prisoner with the longest serving of a death sentence in the world.

His lawyers continued to fight on his behalf, arguing that DNA recovered from the allegedly blood-stained clothing used to frame him did not match.

Judge Hiroaki Murayama recognized in 2014 that ‘the clothes were not those of the accused’.

Kumamoto Norimichi, one of the three judges in his case, said during the trial that he did not believe there was enough evidence to convict him.

“As for the evidence, there was almost nothing more than the confession, and this had been obtained under intense interrogation,” he said.

Norimichi resigned after failing to convince the other two judges.

Former Japanese death row prisoner Iwao Hakamada, left, and his sister Hideko Hakamada attend a meeting of supporters in Shizuoka, central Japan, on Oct. 14, 2024.

Hideko Hakamada, left, sister of former boxer Iwao Hakamada helps her brother, in 2021

Iwao Hakamada is greeted by his fans upon his arrival in Hamamatsu, Shizuoka prefecture, central Japan, on May 27, 2014.

It took nearly three decades for the Supreme Court to deny Hakamada’s first appeal for a new trial. His second appeal for a new trial, filed by his sister in 2008, was granted in 2014.

The court ordered his release from solitary confinement on death row, but without overturning his sentence, pending a new trial.

Hakamada was the longest-serving death row inmate in the world and only the fifth death row inmate to be acquitted in a retrial in postwar Japan, where criminal trials last years and retrials are extremely expensive. rare

His case and acquittal have sparked calls for greater transparency in the investigation, legal changes to reduce obstacles to a new trial, as well as a debate over the death penalty in Japan.