Words often fail my opponents, as they tend not to have many arguments. So in recent years, as I fight for facts and logic on anti-social media, my critics have started calling me “old man” in hopes of hurting me.

A variation on this is to call myself a ‘Boomer’, the American expression for those like me who were born in the great Baby Bulge after World War II (I was born in October 1951).

They make it like it’s a bright spot. They seem to think that because I’m old I’m stupid. This does not embarrass them at all, since it would be equally open prejudices based on race or sex.

My first response to this strange and rather stupid rudeness was to say to myself: ‘Old man? Me?’ As recent research from the Humboldt University of Berlin shows, the age limits have moved a little further in recent years.

Those born in 1911 believed, when they reached 65, that old age began at 71. Those born in 1956 said, at the same stage of their lives, that old age began at 74. But, of course, I’m old , a fact that we at First resisted, then accepted, and now actively welcome. Nowadays I tend to respond to this intended abuse by saying that I hope my critics will one day be lucky enough to be old.

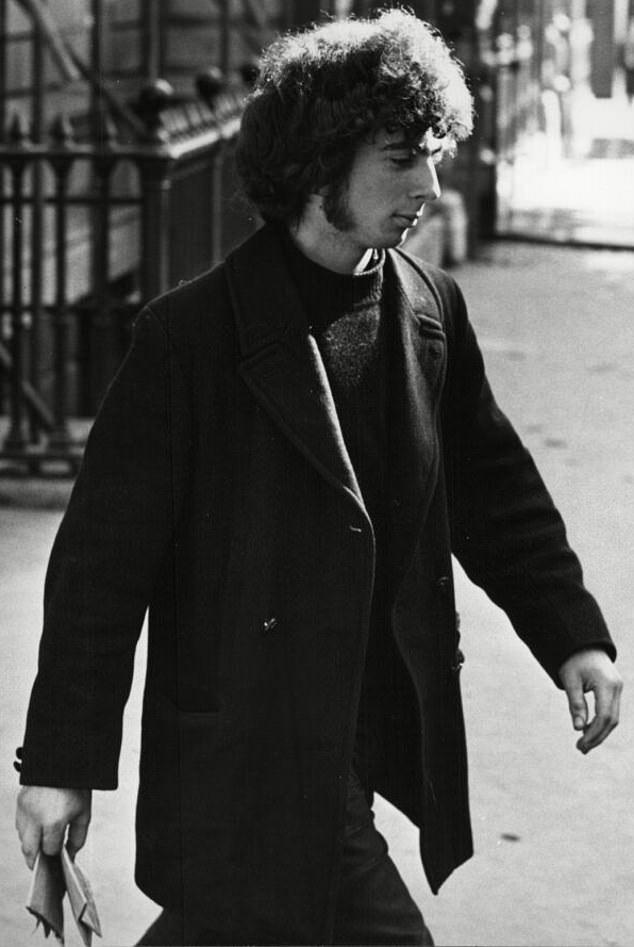

Peter Hitchens in 1969 after being evicted from a hippie squat in Piccadilly, London.

Hitchens, here in 1984, right next to Russia’s Red Square, witnessed the collapse of communism while living in the country.

If you are, you will find one thing: we who are old generally do not feel that we are old. We accept it as a fact, but I am essentially the same person who protested quite vigorously against the Vietnam War in 1968, in London’s Grosvenor Square, where the American embassy was then located.

As it happens, I’m as sure as ever that I was right to do it. Historians have definitely sided with the anti-war movement. An image of this version of me still exists, in case you wanted to forget or suppress this fact.

In fact, as a small celebrity I can, with a few clicks of the computer mouse, see my progress towards retirement age illustrated with numerous photographs and videos. Television clips emerge from the late 1990s onwards, recording the strange behavior of my hair, on my head and face, the curious unwillingness of any clothing to fit my plump peasant body, whether be thin (occasionally) or (more often) fat.

The beards come and go, starting out dark brown and turning gray. During the Great Covid Panic, my hair grows to prodigious lengths, as a deranged government has decreed that it is too dangerous for anyone to get close enough to me to cut it off. Ah, very good then.

If this had gone on much longer, I would have planned to take a full-scale look at Karl Marx in protest of the idiocy of our rulers. One can also trace the exciting success and predictable consequences of a strict diet (kippers and cabbage, plus Listerine mouthwash). The same goes for many other changes, in mentality and direction.

At what point in all this did I think I was getting old? Never, until the teasing started, after which I thought I’d better enjoy it. As that excellent novelist Kingsley Amis said about another inevitable part of life (death), there is no need to request it, no need to stand in line, no need to pick it up. ‘They bring it to you, for free!’

Hitchens returns to Russia after ten years in 2002 to see if life has improved now that the country is no longer under Soviet rule.

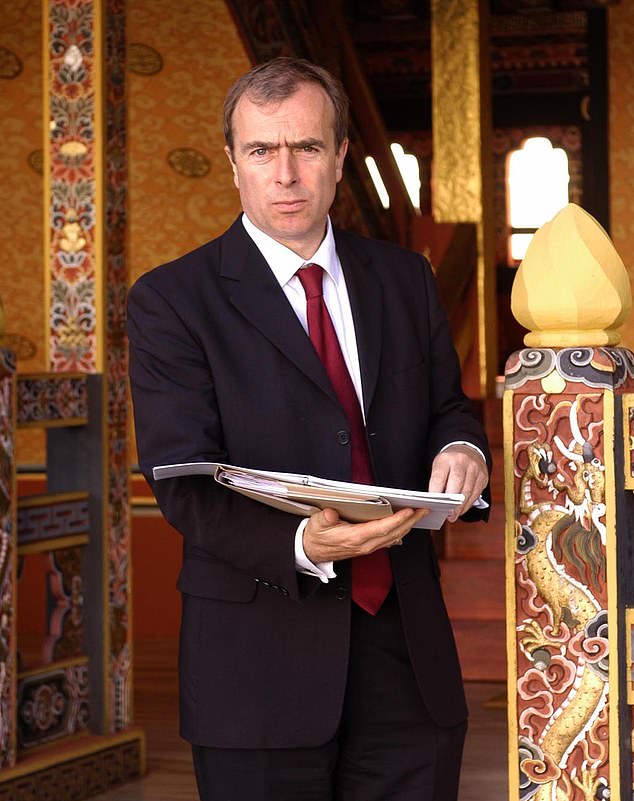

Meeting with then Bhutanese Home Secretary Jigme Thinley in his office at Dzong in the capital Thimphu in 2004.

Now 72, Hitchens tells his critics that one day they will be lucky enough to be old.

So here I am, after three score and ten years, more than two years of extension and remaining firmly of the opinion that I really can’t complain about what happens next. By and large, my generation hasn’t treated their bodies like temples, and every few weeks another 1960s rock star, ravaged by Bourbon and cocaine, bites the dust, often significantly younger than me.

The great institutions of my time are becoming weaker and weaker. I used to wonder if The Times, that mighty organ, would give me an obituary when I died. Now I wonder which of us will be the first to go.

And then there are the advantages. I am old enough to have been educated before the revolution. I knew England before the roads were so full of cars that children couldn’t be let out alone.

I know what ‘Button A’ and ‘Button B’ were back in the days when we had phone booths. I’ve had Fry’s ‘Five Boys’ chocolate bars. I know things about history and poetry that most people don’t even know they don’t know.

What I used to (rightly) consider a rather spotty education now makes me sound like an intellectual (a description I absolutely reject, since I can remember what really well-educated people were like and I can also remember the right teachers). I have failed an exam. I saw express steam locomotives whistling and chugging at stations on winter nights, glowing bright red and orange, and it was normal.

I saw the last major battleship of the Royal Navy, HMS Vanguard, towed into the waves on a muggy summer afternoon in 1960. I saw and smelled Paris almost 60 years ago, before it was modernised. I booed Liberal leader Jeremy Thorpe in 1974 on the steps of 10 Downing Street (then open to all) as he entered to discuss a coalition with Ted Heath. I saw the deep blue stratosphere and the curve of the Earth’s surface from the flight deck of the Concorde.

I watched one of America’s last great luxury trains, the Southern Crescent, leave Washington’s Union Station on its way to New Orleans, with white-clad waiters serving mint juleps to the lucky passengers.

I queued at the Downing Street receptions to be greeted by Margaret Thatcher, who first took me by the hand and then shoved me roughly forward and past her, to let me know that I, a person of no importance, was not expected to remain in his presence. . The future Sir Anthony Blair told me to sit down and stop being mean after I asked him an awkward question at a press conference.

Many times I passed the Berlin Wall and watched the gigantic Red Army roar through the streets and roads of East Germany and shake the Soviet-controlled sky with sonic booms. I stood in the icy snow, warmed by a pair of communist-made long johns, as Marxism-Leninism collapsed in Prague in 1989.

Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev asked me for my vote (which I did not have). I saw a Soviet naval admiral put a plate of pastries in his briefcase at a reception in the Kremlin, because at that time even he couldn’t get decent food in Moscow stores.

The Islamist gangsters in Mogadishu scared me half to death. I attended a divine service on a nuclear missile submarine and walked through the radioactive dust of a nuclear test site. I was chased down a street in Berlin by the East German People’s Police (I ran faster than them) and denied entry to a rather interesting looking bar in North Korea.

I have seen groups of prisoners at work, two American executions, a Soviet massacre, and several Nazi concentration camps. I crossed the International Date Line from Monday morning to Sunday afternoon before, on a trip between Siberia and Alaska that I doubt anyone can make now. Wouldn’t you like to be old too?