It’s almost too good to be true. A doctor you’ve seen on TV for decades promoting a revolutionary new product on social media that big pharmaceutical companies pray you don’t hear about and that could cure what ails you.

But not everything is as it seems. Scammers are increasingly using artificial intelligence technology to fake videos of famous TV doctors, such as Hilary Jones, Michael Mosley and Rangan Chatterjee, in order to promote their products to unsuspecting audiences on social media.

A new report, published in the prestigious journal British Medical Journal (BMJ), has warned about the growing rise of so-called ‘deepfakes’.

Deepfaking uses artificial intelligence to map the digital image of a real human onto a video of a body that is not their own.

They have been used to create videos of politicians to make them look inept and even for corporate theft and now they are being used to sell you dubious “cures”.

Scammers are increasingly using artificial intelligence technology to fake videos of famous TV doctors such as Hilary Jones, Michael Moseley and Rangan Chatterjee to promote their products to unsuspecting members of the public on social media.

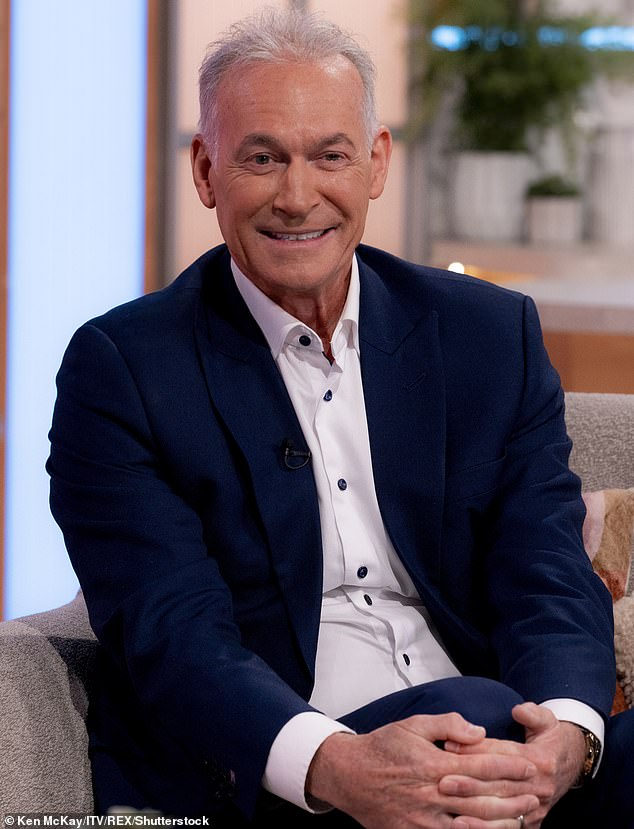

Dr. Jones is just one TV doctor who has jumped on the bandwagon: A deepfake video of him promoting a cure for high blood pressure was circulated on Facebook earlier this year.

And as Dr. Jones himself knows, he is far from the only example.

“Some of the products currently being promoted using my name include those claiming to address blood pressure and diabetes, along with hemp gummies with names like Via Hemp Gummies, Bouncy Nutrition and Eco Health,” he said.

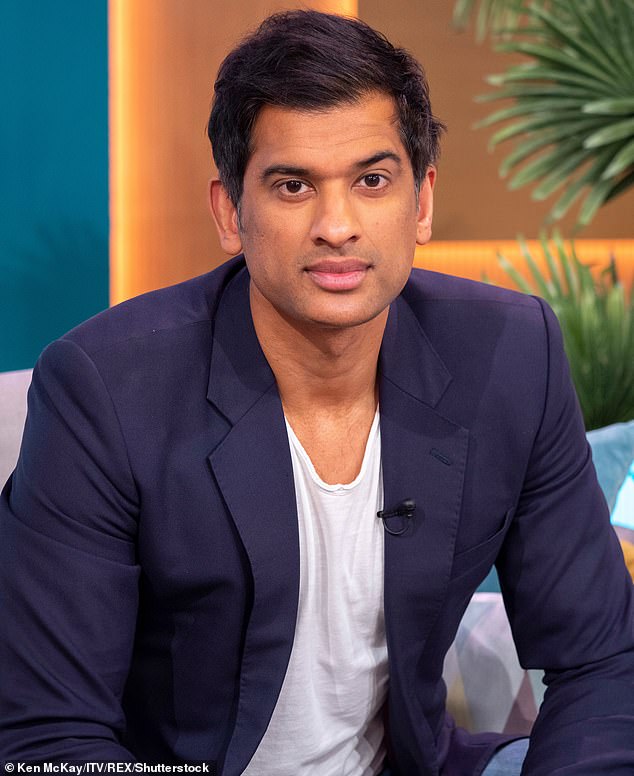

Mail order health guru Dr Mosley, who died last month in Greece, and Dr Chatterjee, famous for his Doctor In The House show, have also been used to generate such clips.

While the technology used to create deepfakes has been around for years, early versions were glitchy, often making mistakes with ears, fingers or failing to match audio to the subject’s lip movements and alerting people to their fraudulent nature.

But huge strides have been made since then, and although research is limited, data suggests that up to half of people have difficulty distinguishing them from the real thing.

Retired doctor John Cormack, who worked with the BMJ on the report, described fraudsters who exploit the reputations of respected doctors to promote their products as “printing money”.

“The bottom line is that it’s much cheaper to spend money on making videos than on researching, creating new products and bringing them to market in the conventional way,” he said.

Regulators also appear powerless to stop the trend.

Practising doctors in the UK must be registered with the General Medical Council, which, if a doctor is found to have failed to meet the standards expected of medical professionals, can suspend them from their job or even strike them off altogether.

Scammers are also using the voice and image of Mail health guru Dr Michael Mosley, who died last month in Greece, to promote their products.

But they have no power to act on fake videos of doctors and while impersonating a doctor is a crime in the UK, the murky world of the internet makes tracking down who to hold accountable almost impossible, especially if they are based abroad.

Instead, doctors like Dr Jones say it is the social media giants who host this content and ultimately make money from it that need to take action.

“It’s up to companies like Meta, which owns Facebook and Instagram, to prevent this from happening,” he said.

“But they are not interested in doing so as long as they are making money.”

Responding to the BMJ report, a Meta spokesperson said: We will investigate the examples highlighted by the BMJ.

‘We do not allow content that intentionally misleads or seeks to defraud others, and we are constantly working to improve detection and enforcement.

‘We encourage anyone who sees content that may violate our policies to report it so we can investigate and take action.’

At this point, doctors like Dr. Jones have to take matters into their own hands.

Dr. Jones, a frequent guest on shows like Lorraine, employs a company to track down deepfakes involving him and try to purge them from the internet.

But he added that the scale of the problem only appears to be getting worse.

Dr Rangan Chatterjee, from the BBC documentary Doctor In The House, has also been drawn into the trend.

“There has been a huge increase in this type of activity,” he said.

“Even if they are deleted, they appear the next day under a different name.”

The report concludes by saying that what makes deepfakes so insidious is that they play on people’s trust, leveraging a familiar face that has offered good, sometimes life-changing, health advice in the past to scam worried patients.

People who see a video they suspect is a deepfake are advised to first examine it carefully to avoid a “boy who cried wolf” situation.

If you are still suspicious, try to independently contact the person who supposedly appears in the video through a verified account, for example.

If you still have suspicions, consider leaving a comment questioning its veracity so that hopefully others will take that extra step of analysis as well.

People can also use social media’s built-in reporting tools to flag both the video and the person who posted it in an attempt to get it removed.