- New report says Kennedy family members stepping up efforts to help Biden’s re-election could take different forms

- This comes after several Kennedys joined Biden for St. Patrick’s Day at the White House

- RFK Jr.’s Independent White House Bid Could Be a Spoiler for Biden in November

<!–

<!–

<!– <!–

<!–

<!–

<!–

As Robert F. Kennedy Jr. prepares his independent bid for the White House, some members of the extended Kennedy family are expected to begin a more active effort to help President Joe Biden win re-election in November, according to a new report.

On Sunday, dozens of members of the generations-old political dynasty gathered at the White House for St. Patrick’s Day where they were photographed posing on the steps of the Rose Garden with President Biden.

“From one proud Irish family to another, it was good to see you all back at the White House,” Biden posted on social media in response to a post with the photograph of Kerry Kennedy, the youngest daughter of the late Senator Bobby Kennedy and his sister. to RFK Jr.

Other Kennedys in the photo included Kerry’s daughter Mariah Kennedy-Cuomo, sister Rory Kennedy, former Rep. Joe Kennedy III, who is Biden’s special envoy to Northern Ireland, and former Rep. Patrick Kennedy .

A senior member of the Kennedy family said NBC News it was important that everyone was there for the gathering.

The senior member added: “I think timing is everything. »

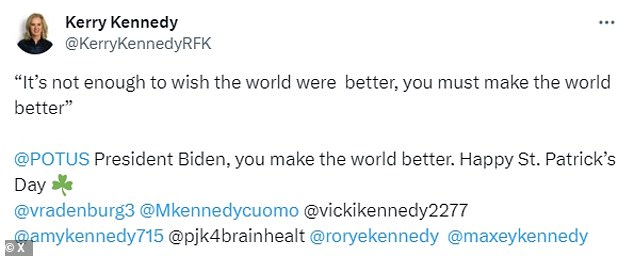

Robert Kennedy Jr.’s sister, Kerry Kennedy, and other family members posted this group photo of Kennedy family members alongside President Joe Biden at the White House on Sunday to celebrate St. Patrick’s Day.

Kerry Kennedy said while sharing family photo with President Joe Biden: ‘you make the world a better place’

An NBC News report indicates that members of the Kennedy family are ready to step up their efforts to help Biden’s campaign as Robert Kennedy Jr. runs as an independent in the 2024 election.

According to the NBC News report, people close to the family say that strengthening the Kennedys’ commitment could take different forms.

Some family members expect to spend time on the campaign trail this fall, which could mean more media appearances or lending their names to initiatives to counter Kennedy’s campaign for others.

It comes as Kennedy’s independent bid for the White House is seen as a potential spoiler that helps former President Donald Trump while hurting Biden’s re-election bid in November.

Recent polls in several battleground states show that, with Kennedy in the race, Trump’s lead is expanding in crucial swing states that Biden must win to win re-election.

NBC reported that several sources familiar say the Biden camp is letting the Kennedys take the lead in helping the president’s campaign.

Since Kennedy launched his candidacy nearly a year ago, first as a Democrat last April before becoming an independent in October, a number of his family members have spoken out against his run for the House White.

“Our brother Bobby’s decision to run as a third-party candidate against Joe Biden is dangerous for our country,” his siblings Rory, Kerry, Joseph P. Kennedy II and Kathleen Kennedy Townsend said in a statement last fall.

They said that although Bobby shares the same name as their father, “he does not share the same values, the same vision or the same judgment.”

Polls show Kennedy’s inclusion hurts Biden as Trump’s lead grows in swing states

Robert F. Kennedy Jr. (right) appeared on Chris Cuomo’s (left) NewsNation show Monday night and insisted that many members of his family support his independent presidential campaign against President Joe Biden.

On Monday, Kennedy was asked in an interview on NewsNation about messages from his family members gathered at the White House with Biden. Kennedy insisted he had family supporting his campaign.

“Well, first of all, I would like to point out, as you know, Chris, even though it seems like a big crowd of people. It’s a very small percentage of my family,” Kennedy told host Chris Cuomo . “Last July 4, I think there were 105 people in Cape Town.”

“And many other members of my family work for my campaign, many other members of my family support my campaign,” he added.

Asked about reports that members of the Kennedy family are stepping up, DNC spokesman Matt Corridoni said a picture is worth a thousand words.

‘It’s telling that the people who know RFK Jr. best are standing with Joe Biden in this election.