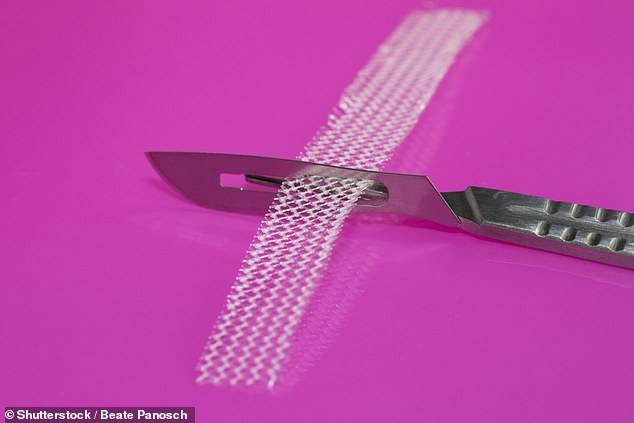

The material commonly used in vaginal mesh implants begins to degrade within 60 days after being implanted in the pelvis, according to a new study.

The researchers also found particles of polypropylene, a type of thermoplastic, in the tissue surrounding the implant sites.

Activists called for “immediate action” by the medical community and regulatory bodies based on the findings “to ensure this dangerous product does not destroy more lives.”

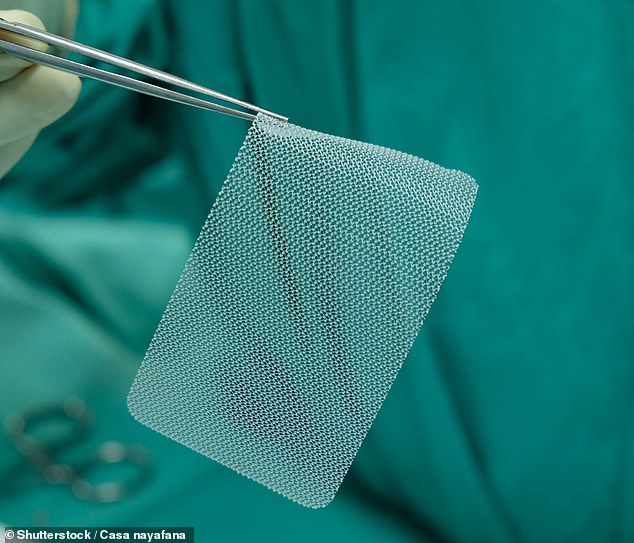

Transvaginal mesh (TVM) implants, made from synthetic materials such as polypropylene, have been used to treat pelvic organ prolapse and stress urinary incontinence, but can cause debilitating damage to some women.

Side effects have included infection, pelvic pain, difficulty urinating, pain during sexual intercourse, and incontinence.

Activists called for “immediate action” from the medical community and regulatory bodies (file photo)

Transvaginal mesh (TVM) implants, made from synthetic materials such as polypropylene, have been used to treat pelvic organ prolapse and stress urinary incontinence (file photo)

The NHS restricted the use of TVM implants in 2018 and they are now used only as a last resort through a high surveillance restricted practice programme.

The study by scientists at the University of Sheffield looked at polypropylene mesh implanted in sheep, which share a similar pelvic anatomy to women.

They found that the fibers began to degrade within 60 days, becoming stiffer and showing signs of oxidation, a process that increased over time.

The researchers also discovered polypropylene particles in the tissue around the implantation site.

According to the study, the concentration of these particles was 10 times higher after 180 days than after 60 days.

Sheila MacNeil, emeritus professor of biomaterials and tissue engineering at the University of Sheffield, said: “This research provides objective physical evidence that this material does not resist implantation in the pelvis well.

‘This is crucial because it is imperative that we develop new and better materials for the thousands of patients suffering from stress urinary incontinence and pelvic organ prolapse.

“We now know how to critically evaluate any problems related to new materials before implanting them in women.

“It is essential to have tests to detect possible failures in materials, rather than testing untested materials on patients.”

The research, published in the Journal of the Mechanical Behavior of Biomedical Materials, suggests that the polypropylene surgical mesh “was not tested for suitability at the implantation site,” but rather “an assumption was made based on the success of the polypropylene mesh used to treat abdominal hernias. that the same mesh would work just as well on the pelvic floor.’

The researchers also discovered polypropylene particles in the tissue around the implantation site (file photo)

Side effects include infection, pelvic pain, difficulty urinating, pain during sexual intercourse and incontinence (file photo).

It comes after more than 100 women in England with complications from vaginal mesh implants received payments as part of a group settlement.

Study leader Dr Nicholas Farr, a researcher at the University of Sheffield, added: “Our results provide strong evidence for the instability of polypropylene and offer new insights into the mechanisms that contribute to its degradation in the body.”

‘While the recent monetary compensation for affected patients is certainly a welcome development, there remains an urgent clinical need for safer materials to address pelvic organ prolapse.

“I hope that current and future mesh manufacturers recognize the insights from this study and contribute to the continued development of safer alternatives.”

Kath Sansom, founder of the Sling The Mesh support group, which has almost 11,000 members worldwide, said the findings “provide even more damning evidence about the dangers of polypropylene mesh.”

“The community affected by the mesh has suffered debilitating complications, unaware that the plastic material implanted in their bodies is not fit for purpose and could degrade so quickly,” he said.

‘This study confirms what many of us suspected: that the mesh becomes unstable and causes irreversible damage.

“It is critical that this new research be used to drive immediate changes in medical practice, including the need for surgeons to relearn traditional skills using reliable native tissue methods to correct prolapse and stress incontinence, without plastic mesh.” .

‘Patients deserve better. We must avoid further suffering.”

Ms Samson, a former journalist and mother-of-two from Cambridgeshire, added: “The mesh community were confident their treatment was safe but had to deal with chronic pain, infections, loss of mobility, autoimmune diseases and even damage to organs and “Removal of organs where the plastic material has become brittle, acting as an internal knife that cuts tissues and nerves,” he added.

‘It is completely unacceptable that so many people have not been informed of these risks.

“The medical community and regulatory bodies must take immediate action based on this research to ensure that this dangerous product does not destroy more lives.”

Dr Alison Cave, chief safety officer at the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA), said: “Patient safety is our top priority and the use of surgical mesh to treat stress urinary incontinence and urinary prolapse pelvic organs has been subject to restrictions since July. 10, 2018.

‘Exceptions are made in cases where this type of mesh may be the only suitable treatment option for a woman.

“However, it should only be used in carefully selected patients who have been informed and understand the benefits and risks, and in whom all other treatment options have been explored.”