Mary Poppins (Rapcourse, Bristol and tour)

Verdict: Next Generation Poppins

Plays of West End hits don’t always do well on tour. Reviews are available; and creatives, actors and technicians may be tempted to relax. Shows can start to creak, shortcuts are taken and ambition is reduced.

But James Powell’s reboot of Richard Eyre’s 2019 production, which premiered at London’s Prince Edward Theatre, has somehow improved along the way. In addition to its shiny, cheerful and familiar features, it has acquired what I can only describe as… edge!

The cozy, middle-class Edwardian asylum of Cherry Tree Lane in the PL Travers stories, made famous by Julie Andrews and Dick Van Dyke in the 1964 film, has changed. The two kids are still freaking out. Mr. Banks, the punctilious Edwardian father who works in finance, remains a lovable stiff. His wife Winifred still has an edgy charm, while the virtually perfect Mary Poppins comes to the rescue, after her wild offspring dispatches a long line of nannies.

However, in a show where surprises didn’t seem possible, Australian actress Stefanie Jones is a revelation as Mary. She also (unlike her character) didn’t come out of nowhere. He settled into the role Down Under opposite Jack Chambers as his suspiciously quiet “friend”, Bert the chimney sweep (a role he reprises here). Naturally, Jones covers all the bases. Feet in first position. Gloved hands resting on an avian stick. A fruity warble in his voice. High precision dance steps. And an incomparably superior attitude.

Yet there’s something extra, something intriguingly android about her bearing, as if she were a next-generation AI nanny. She is a very convincing human, but she also creates a strange uncertainty. Is she real… or an incredibly realistic robot? Fear not, however; These inferences could simply be the product of my feverish imagination.

The show is built on excellence and moment-to-moment delight. Father Basil Fawlty-ish by Michael D. Xavier. Lucie-Mae Sumner’s kind northern mother. Wendy Ferguson’s former nanny from hell, Miss Andrew. Rosemary Ashe’s nutty cook and Ruairidh McDonald’s silly bottle washer.

James Powell’s reboot of Richard Eyre’s 2019 production, which premiered at London’s Prince Edward Theatre, has somewhat improved along the way.

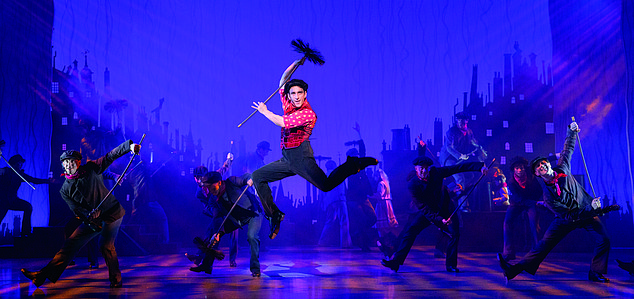

Jack Chambers as Bert the Chimney Sweep

In a show where no surprises seemed possible, Australian actress Stefanie Jones is a revelation as Mary

The children (alternating roles) are also fantastic, precocious but not painful, as Patti Boulaye haunts the show as Bird Woman, singing Feed The Birds.

The show’s illusions still defy the eye, with Mary’s magic carpet delivering its unlikely cargo of floor lamps, potted plants and a tea set.

The gray park transforms like a pop-up book into a jungle of flowers atop dancing statues. And the chaos in the kitchen that marks the song A Spoonful Of Sugar works like a Swiss clock.

But then again, there’s something about the way the video projections glow on the seemingly painted floors of the dollhouse layout that suggests something supernatural.

As for the music of the Sherman Brothers, Chim Chim Cher-ee, Practically Perfect and other Poppins standards played to six. And Richard Jones’ revival of Matthew Bourne and Stephen Mear’s choreography works like another Swiss clock… a cuckoo clock.

Twice the company raises the roof: first with Supercalifragilisticexpialidocious in the confectionery, and then with the chimney sweeps’ tap dance in which Bert, suspended from cables, dances upside down over the proscenium arch.

I saw the original in London with my two daughters. We loved it then, but now I think I’m going to need another star.

Mary Poppins is at Bristol Racecourse until November 30. For more tour dates, visit marypoppins.co.uk.

The children (alternating roles) are also fantastic, precocious but not painful, as Patti Boulaye appears in the show as Bird Woman, singing Feed The Birds.

I saw the original in London with my two daughters. We loved it then, but now I think I’m going to need another star.

Digging for Gold (Park Theatre, London)

Verdict: Needs a dramatic punch

THERE is nothing more annoying in the theater than the person next to you munching on a packet of crisps, unless, of course, that person is former WBC light heavyweight boxing champion John Conteh.

Such was my good fortune this week, in a sweet but rambling tribute to Conteh’s late friend and former flatmate, Frankie Lucas.

Born in 1953, Lucas arrived in London from the Caribbean island of St. Vincent at the age of nine, eager to box.

Training with Yorkshire copper Ken Rimmington in Croydon, he beat British golden boy Alan Minter at the Albert Hall in 1972, only to see Minter chosen to represent England at the Olympics. Lucas, again overlooked at the 1974 Commonwealth Games, decided to fight for St. Vincent and won gold, eliminating England’s Carl Speare in the semi-final.

Hoping for better salaries, Lucas changed his coaches to those of the legendary George Francis, who mentored Conteh and, later, Frank Bruno.

But his career declined and Francis began to worry about Frankie smoking marijuana. Lucas began to imagine that the devil was in his left hand, and not in a good way. (To prevent it from escaping, I would keep it closed. Permanently.)

Chatting in the interval, Conteh told me that Frankie was driven by anger; and although Lisa Lintott’s work speaks to that rage, it is primarily a rosy portrait of a sweet and gentle soul.

Like Frankie, Lisa’s son, Jazz Lintott, is docile and patient. I never felt the fire of a fighter so fearsome that he was nicknamed the “wild man of the ring.”

Cyril Blake is warm and cheerful as Ken, Lucas’s first mentor; while Nigel Boyle is a patrician and tough George, reminiscent of Henry Cooper. Daniel Francis-Swaby is charming as Michael, Frankie’s beloved son.

And although directors Philip J. Morris and . .

I was amused, for example, to hear Frankie associated with the 70s reggae hit Johnny Reggae (“he’s a very tasty old man”). And I’m glad to know that his character dispels rumors that he once made out with Princess Anne. After all, as his father commented, “If he doesn’t fart and eat hay, he’s not interested.”

How to Survive Your Mother (King’s Head Theatre, London)

Verdict: Monster Mom

This unflinching portrait of his mother by former BBC journalist turned playwright Jonathan Maitland is a work of high-level masochism.

It’s one thing to have had a seriously dysfunctional relationship with your mother. It’s quite another to write it, adapt it to the stage, and appear on it (as Maitland does here), night after night, for a marginal salary in the theater.

Ma Maitland is presented as a Jewish lioness with an Eastern European accent wearing a leopard skin dress, in other words, a very confused cat.

While her son was growing up in the 1960s and 1970s, she… pretended to be dead, didn’t go to boarding school (which she couldn’t afford), tried to bribe inspectors at her dodgy nursing home, and converted her residence from Surrey in a gay guest house called ‘Homolulu’.

Maitland’s work is filled with fantastic dialogue and a great deal of profanity. “The F-word,” he explains, was not a bad word to his mother. It was “score.”

Furthermore, his tendency to wrap his story in protective humor leads a psychiatrist (also in the play) to suggest that he uses comedy as a defense. His answer is that if you get rid of your defense you lose (“like Newcastle did with Kevin Keegan”).

Emma Davies acquits herself admirably as Maitland’s toxic, devious, manipulative, lying and delusional mother, who at one point claims to have “eyebrow cancer”. But in a psychologically fascinating move, she also plays his wife and psychiatrist.

Oliver Dawe’s production struggles to create dramatic unity, not helped by the fact that Louie Whitemore’s all-white set lacks much sense of time or place. Instead, this is provided by a soundtrack featuring Showaddywaddy, Randy Edelman, and Herb Alpert.

Perhaps out of modesty, Maitland doesn’t tell us too much about himself, so the main question of how he survived his mother remains a mystery.

What we do know is that he is now an accomplished writer of excellent works on Princess Diana, Jimmy Savile and the Johnsons (Wilko and Boris).

Here, however, it is more of a cipher, reduced to regretful glances.

And although he shares his role with a child actor and another actor (who plays him as a thirtysomething), finding someone else to play him in middle age might have given him more creative freedom and spared him the nighttime agonies.