A boy confessed to shooting a 32-year-old stranger while he slept in a Texas trailer park two years ago, when he was just seven years old.

The unnamed boy, now 10, was caught this month after his school principal reported him to police for allegedly threatening to “assault and kill another student on a bus.”

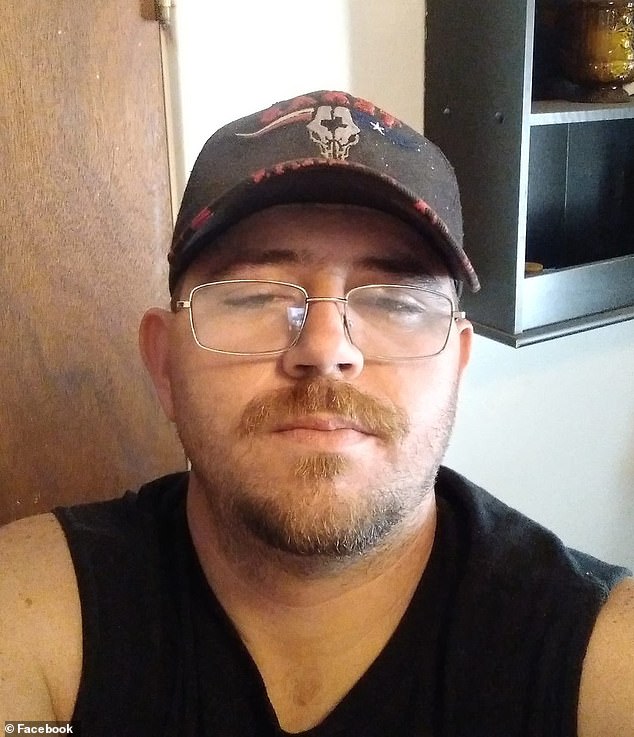

He was later interviewed and admitted to shooting and killing Brandon O’Quinn Rasberry, 32, who was found dead at Lazy J RV Park on Jan. 18, 2022, in Nixon.

The boy will not face murder charges due to his age, but was taken to a psychiatric facility for evaluation and treatment.

Rasberry’s father, Kenneth, told KSAT: ‘He is forgiven. And he can still be saved. He is so young. He’s definitely tormented by something.’

Brandon O’Quinn Rasberry, 32, was found dead at Lazy J RV Park on January 18, 2022, in Nixon.

He was found dead in his mobile home with a single gunshot wound to the head and the cause of death was listed as homicide.

Rasberry was found dead in his mobile home with a single gunshot wound to the head and the cause of death was listed as homicide.

For more than two years, police struggled to find a suspect and his family was forced to launch their own investigation, writing: “We will leave no stone unturned in our search for the truth about what happened to you, Brandon Rasberry.”

He had moved to the park just days before his death and was working at Holmes Food in Nixon; His body was found after he did not show up for work for two days.

As police struggled to find a suspect, his family were left “incredibly heartbroken” by his death, labeling him a “special, kind, generous and loving soul.”

Then this month, a Nixon Smiley Independent School District principal called the Gonzales County Sheriff’s Office to report a boy for allegedly threatening to “assault and kill another student on a bus.”

When police interviewed the principal, they were told that “the boy stated that he shot and killed a man two years ago.”

The boy was then taken to a child advocacy center where officers interviewed him and revealed firsthand knowledge of Rasberry’s murder.

He told officers he was staying at the trailer park with his grandfather when he took a 9mm handgun from the glove compartment of his grandfather’s truck, entered Rasberry’s trailer home and shot him in the head while he was sleeping. .

He then shot the couch in his motor home and returned the gun to the glove compartment.

He said he didn’t know Rasberry, but he had seen him walking in the park earlier that day and said he had no reason not to like him.

For more than two years, police struggled to find a suspect and his family was forced to launch their own investigation.

The boy was captured this month after his school principal reported him to police for threatening to “assault and kill another student on a bus.”

He has not been charged with murder as he was only seven years old at the time and Texas law does not allow criminal culpability before age 10.

The Sheriff’s Office said: “When questioned, the boy stated that he had never met Brandon and did not know who he was, although he had observed him walking around the mobile home earlier that day.

“They also asked the boy if he was angry at Brandon for any reason or if Brandon had ever done anything to him to make him angry, the boy said no.”

Investigators then found the gun at a pawn shop in Seguin, Texas, and bullet casings from the scene matched the gun.

The boy was taken to a psychiatric hospital in San Antonio for evaluation and treatment and then to the Gonzales County Sheriff’s Office and charged with terroristic threatening for the school bus incident.

He has not been charged with murder as he was only seven years old at the time and Texas law does not allow criminal culpability before age 10.

Rasberry’s family was shocked to learn that their son’s killer was a boy.

The victim’s father, Kenneth, told KSAT, “This is not the suspect we thought he was.” This is a little kid, for reasons that I’m sure these counselors and case managers and all that, are going to wreck that poor kid’s brain.

‘He needs to be prayed for. He needs to be comforted…he is forgiven. And he can still be saved. He is so young. He’s definitely tormented by something.