Roman Kemp thanked his listeners for “saving his life” during his battle with depression as he presented his final show on Capital Breakfast on Thursday.

The radio host, 31, who is leaving the station after 10 years, credited the show and his listeners for helping him get through some of his darkest days.

During his last show, Roman gave a moving speech in which he said how grateful he was to them for bringing “light and laughter into his life” during his radio appearance.

Roman became emotional as he said: ‘I know there are a lot of people listening right now and I wanted to take the time to thank them. I was more nervous about saying I was leaving than I was about leaving this show.

“This show is run by a lot of people behind the scenes who try really hard to give you some energy in the morning and try to get you up and feeling good, but I think what I want to convey is how much fun I’ve had on this station in the last ten years.

Roman Kemp thanked his listeners for “saving his life” during his battle with depression as he presented his final show on Capital Breakfast on Thursday.

The radio host, 31, who is leaving the station after 10 years, credited the show and his listeners for helping him get through some of his darkest days.

‘It has changed my life in many ways and I have grown in this place, and that is because you all listened to me. You have been able to be there for me in things I never imagined would happen.

‘I’ve had moments on this show where my whole life outside of work is completely ruined. There were times when I didn’t want to be here anymore. There have been times when my life outside of this room has been the worst.

‘I know a great life, but in my head this is how it feels. I knew that all I had in my life were those four hours of my day where I could come to work and in those four hours I knew I was going to laugh and have fun and be surrounded by people who understood me and those four hours. And those people I’m talking about include you, the listeners. You have no idea how much you’ve helped me.’

Roman continued: ‘I want to thank you for listening to every text, every call, everything. I appreciate it more than you will ever know. I have had a lot of fun and I owe a huge debt to this company for being able to bet on me.

“I was terrified to take over this program and I’m terrified to leave it. But sometimes with these things, you just know when the right time is to move on and that time is now for me.

‘You’ve helped me a lot and you’ve always had my back and it’s been amazing. Honestly, from the bottom of my heart, you have truly saved my life at certain times.’

Roman got ready to perform his latest Capital Breakfast show and made sure to dress for the occasion.

He revealed he was leaving the show in a statement last month, after 10 years of presenting for the station.

During their latest show, their co-stars Sian Welby and Chris Stark fought back tears as they dressed in black blazers and bow ties.

Sharing a series of behind-the-scenes photos on Instagram, Roman shared a selfie from behind the desk.

“The last one,” she captioned the snap, while another showed Sian crying.

After the show, Roman will be replaced by 34-year-old Jordan North.

On Wednesday, Roman fought back tears as his Capital Breakfast colleagues surprised him by presenting the radio show from the Emirates Stadium dressing room.

To mark his penultimate show, his co-hosts Sian and Chris decided to surprise him by blindfolding the star and then taking him to the home of his beloved football club Arsenal.

Speaking to listeners, Chris explained: “So the story is that we’ve been secretly planning this for weeks, and the best thing is that Roman Kemp still has no idea where it’s going.”

The duo then called out to Roman, as their car pulled up outside, and Chris said, “So, to set the scene a little, am I right in thinking that you’re currently wearing a blindfold?”

Roman replied: ‘Well, I’ve been blindfolded for the last hour and a bit, since I’ve been in this taxi.

‘I was a little worried about getting into a car blindfolded and letting it go anywhere. But honestly, I’m starting to get nervous now.

He was then guided out of the car and driven through the stadium, while he tried to guess its location.

Sharing a series of behind-the-scenes photos on Instagram, Roman shared a selfie from behind the desk.

“The last one,” he captioned the photo, while another showed Sian crying.

Roman took off the blindfold and gasped, ‘Oh. My. God! This is crazy!’

He was handed a microphone as Chris said, “Roman, for everyone listening, where are we doing the show this morning, your second to last show?”

An astonished Roman responded: ‘We are in the home of football, we are inside the Arsenal stadium! We’re in the locker room!’

He became visibly emotional when he said: ‘This is crazy, how did you do this? This is crazy. Can I just say that I’m almost crying? I almost cried when I took it off.

‘Is incredible. This is ridiculous. By the way, we are live from inside the dressing room of my favorite in the world. The Emirates Stadium with eBay. This is amazing, isn’t it?

The surprises for Roman didn’t end there, as Chris proceeded to serenade him on guitar with his own personalized rendition of Arsenal terrace favourite, The Angel (North London Forever).

He then challenged Roman to test his knowledge of Arsenal with a quiz about the football club, promising that if he won he could make his childhood dream come true or take a penalty on the Emirates pitch.

Romano added: ‘Tomorrow is the big one. It’s my last show after being in Capital for 10 years. It is the last!’ causing Sian to burst into tears.

Chris asked: ‘Sian, are you crying? Oh no! Why are you crying?’

She replied: ‘Because I suddenly realized that tomorrow is your last show. In fact I’m crying. It’s been crazy… Today has been a really fun day.

‘It’s been so nice to hear from everyone and know how much you’ve meant to them over all these years you’ve done Capital Breakfast.

“Knowing that tomorrow is the last one, and we’ve all been preparing for this for so long, it affected me in that moment just like you said.”

Roman explained that he wanted his last show to be “as normal as possible” with listeners coming on air to talk to them, saying it would be “a chance for me to be able to say a proper goodbye to you.”

Roman joined Capital in 2014 before hosting the prestigious The Capital Evening Show in 2016.

On Wednesday, Roman fought back tears as his Capital Breakfast colleagues surprised him by presenting the radio show from the Emirates Stadium dressing room.

To mark his penultimate show, his co-hosts Sian and Chris decided to surprise him by blindfolding the star and then taking him to the home of his beloved football club Arsenal.

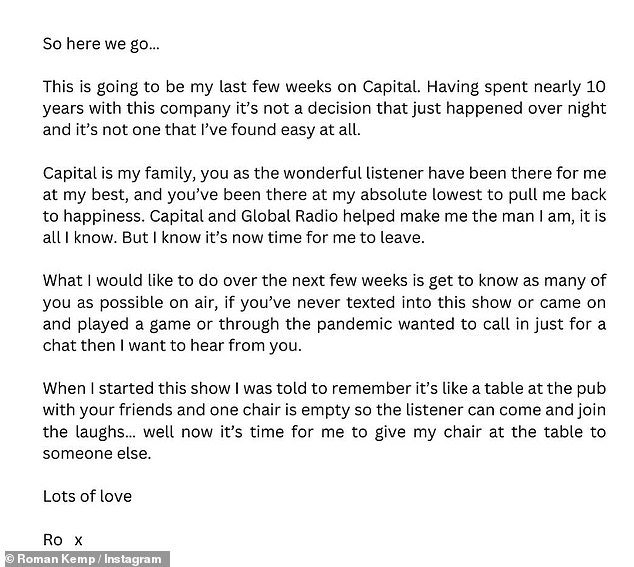

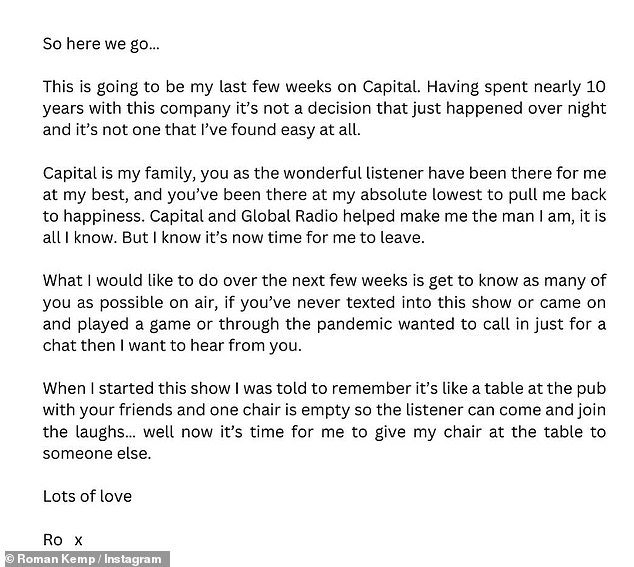

He announced his departure on air last month, before issuing a statement on his social media, where he said Capital was his “family” that brought him out of his “absolute lowest” and helped “make me the man I am.”

In 2017 he moved to Capital Breakfast before taking the show national in 2019.

He announced his departure on air last month, before issuing a statement on his social media, where he said Capital was his “family” that brought him out of his “absolute lowest” and helped “make me the man I am.”

He concluded: “When I started this show I was told to remember that it’s like a table in the pub with your friends and one chair is empty so the listener can come and join in the laughter…

“Well, now it’s time to give up my chair at the table to someone else.”

Listen to Capital Breakfast with Roman, Chris and Sian Monday to Friday from 6:00am to 10:00am across the UK on air and on Global Player.