Former drug trafficker Joaquín ‘El Chapo’ Guzmán is now pleading with a federal court in New York to restore his phone call and visitation rights while he languishes in the ADX Florence super-maximum security prison in Colorado.

The 67-year-old co-founder of the Sinaloa Cartel, who once boasted that he was behind the murder of between 2,000 and 3,000 people, complained that he feels alone since his rights as a prisoner were taken away in a letter he wrote. March 20th.

In the letter, which was filed in court Tuesday, Guzmán pleaded with Judge Brian Cogan to allow his wife Emma Coronel to visit him and asked to be allowed to speak to the couple’s twin daughters by phone.

‘I’m sorry for bothering you again with the request I made to you before regarding my wife, Emma Coronel,’ Guzmán wrote in the letter.

‘I ask you to please authorize her to visit me and bring my daughters to visit me, since my daughters can only visit me when they are on school vacation, since they are studying in Mexico.’

The former cartel boss showed his softer side despite proudly running a drug empire that saw thousands of people murdered and millions more affected by his illegal products.

Joaquín ‘El Chapo’ Guzmán wrote a letter to federal judge Brian Cogan in New York asking that his wife be allowed to visit him in prison and that the two 15-minute phone calls with the couple’s 12-year-old twin daughters be reinstated.

Joaquín ‘El Chapo’ Guzmán’s wife, Emma Coronel, was released from US federal custody in September 2023 after serving 31 months of a 36-month sentence that was handed down by a federal court in Washington, DC in November. 2021 after he pleaded guilty to drug trafficking and money laundering

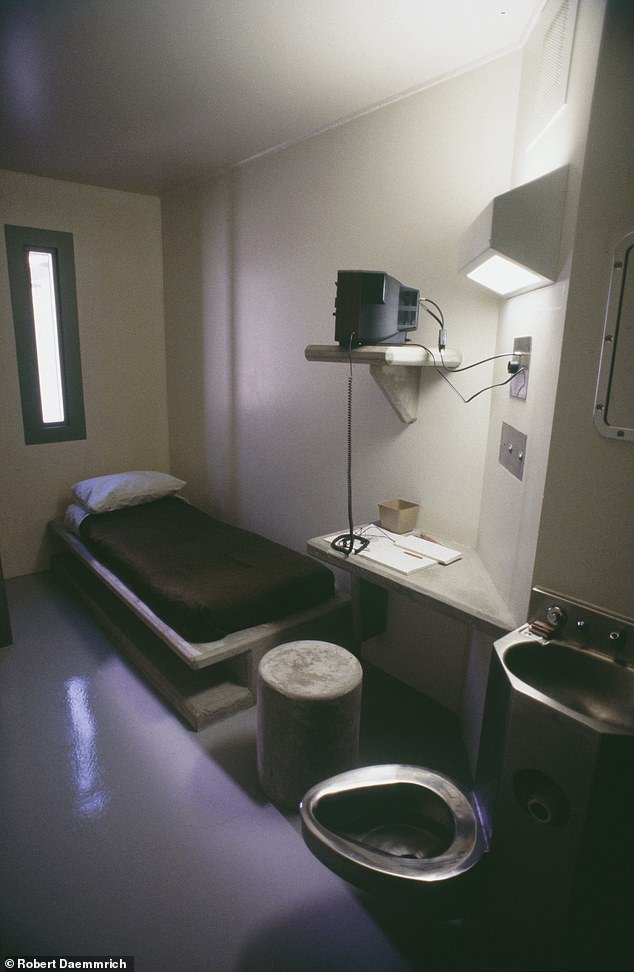

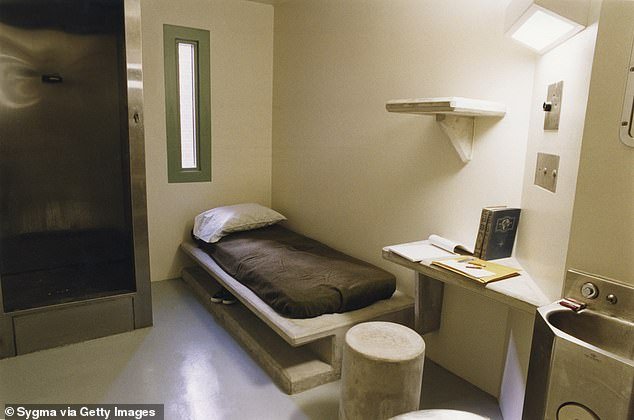

El Chapo spends 23 hours locked in a 7-by-12-foot concrete cell at ADX Florence, a maximum security prison in Colorado

Guzmán also asked Cogan to restore his right to talk to 12-year-old girls twice a month for 15 minutes.

He stated that he had not spoken to them since May 2023, when the jail stopped authorizing phone calls.

‘I have asked when they are going to give me a call with my daughters and the staff here told me that the FBI agent who monitors the calls is not answering,’ he wrote. ‘That’s all they’ve told me. I ask you to please continue giving me the two calls that you authorized me per month. I don’t understand why the prosecutor who is in charge of the SAM Regulation stopped authorizing calls with my daughters.’

The former kingpin spends 23 hours locked in a 7-by-12-foot concrete cell with double doors in a section called “Rank 13.”

He is supervised 24 hours a day and is prohibited from mixing with the inmate population.

Joaquín ‘El Chapo’ Guzmán was convicted by a federal court in New York in February 2019.

El Chapo is only allowed to spend one hour outside the concrete cell where he will spend the rest of his life.

Guzmán has often complained about prison conditions since a federal jury found him guilty in February 2019 of 10 charges that included drug trafficking, money laundering and using a firearm to commit crimes.

In March 2022, his lawyer, Mariel Colón, told the Mexican network Milenio that prison staff were violating his rights.

‘They don’t take him outside, they don’t take him out even for a single day,’ Colón alleged at the time. ‘We have had a lot of problems because they don’t treat him medically if he gets sick. Requests are ignored.’

He claimed that prison staff had also denied El Chapo access to water and dental treatment for his teeth.

She told Univision News in 2019 that he had vision problems and had complained about a bad haircut because barbers couldn’t communicate with him in Spanish.

“He seems much thinner, a little more suffocated. He’s not doing well there,” Colón said at the time. “It’s the saddest I’ve ever seen him.”

Ovidio Guzmán, the son of El Chapo, was extradited from Mexico to Chicago in September 2023 to face charges of drug smuggling across the border

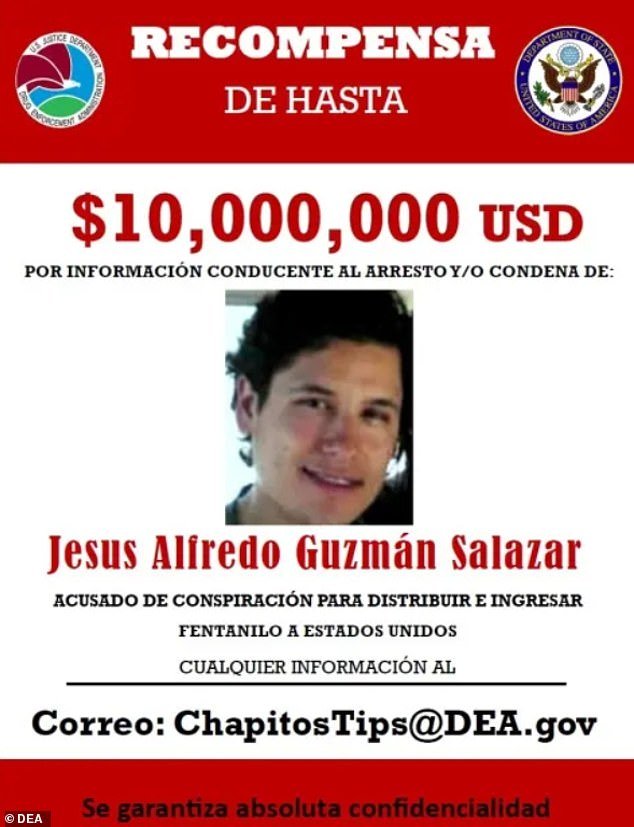

The DEA is offering a $10 million reward for information leading to the arrest and/or conviction of Jesús Guzmán, one of Joaquín ‘El Chapo’ Guzmán’s three who now operate half of the Sinaloa Cartel after his brother, Ovidio Guzmán, was murdered. extradited to the United States last week

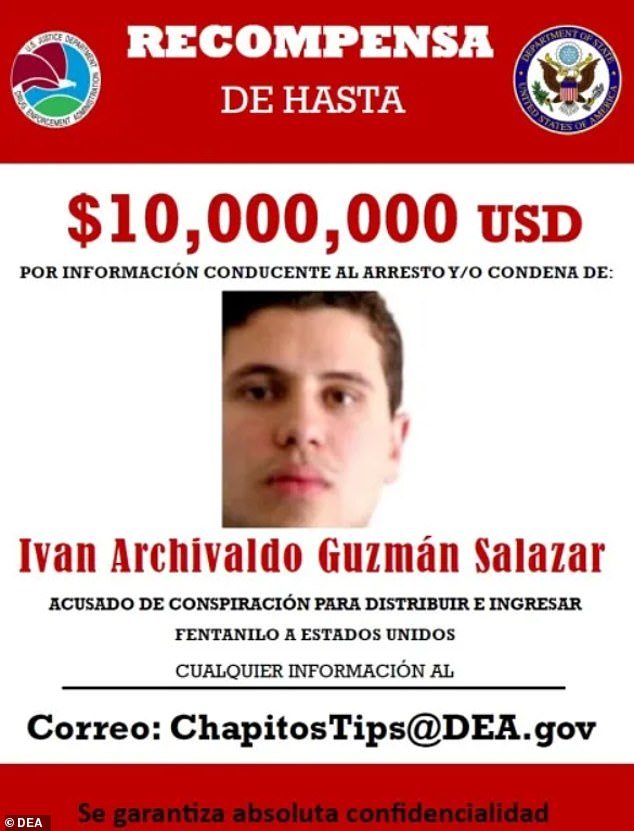

Iván Archivaldo Guzmán Salazar (pictured) joined his brother, Jesús Alfredo Guzmán Salazar, on the DEA’s 10 most wanted list

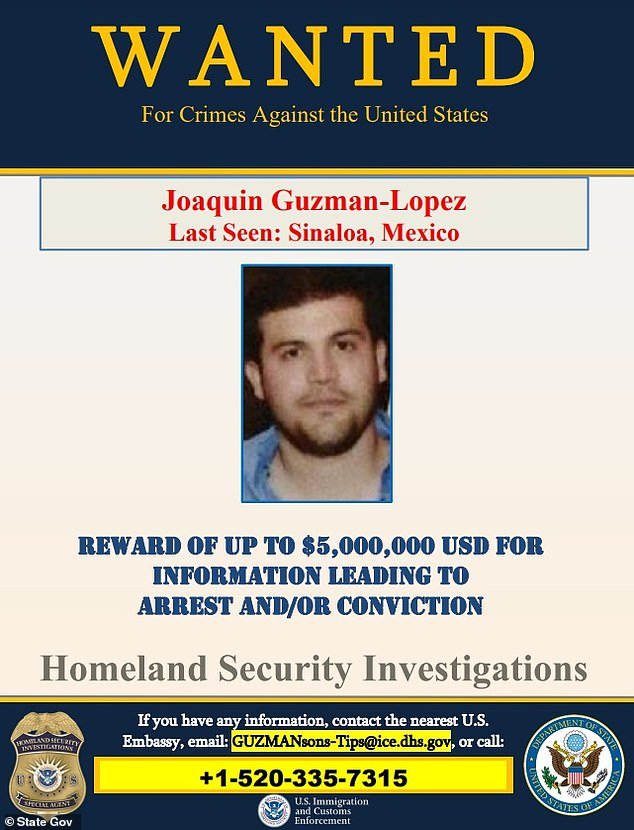

Joaquín Guzmán is one of the four sons of El Chapo who took charge of the Sinaloa Cartel after his arrest and extradition to the United States. But now only three remain in power after his brother, Ovidio Guzmán, was handed over by Mexican authorities last Friday.

Guzmán was once considered the most powerful drug trafficker in the world, after Colombian Pablo Escobar, and was extradited from Mexico in January 2017 after being recaptured in January 2016 following his second prison escape in June 2015 through a tunnel that his organization had built underneath. the jail.

Before that, he had been on the run for 13 years after escaping from prison in a laundry cart in January 2001.

His wife was released from US federal custody in September 2023 after serving 31 months of a 36-month sentence handed down by a federal court in Washington, DC in November 2021 after she pleaded guilty to drug trafficking and money laundering.

His son, Ovidio Guzmán, was extradited from Mexico to Chicago in September to face drug trafficking charges.

Guzmán’s three other sons, Iván Guzmán, Jesús Guzmán and Joaquín Guzmán, are wanted by the US government on similar charges.