It is, without a doubt, one of the most painful injuries we can suffer on a daily basis: it often causes blood and tears.

But a new study by researchers in Denmark may help you avoid the dreaded paper cut, a painful experience for office workers and book readers alike.

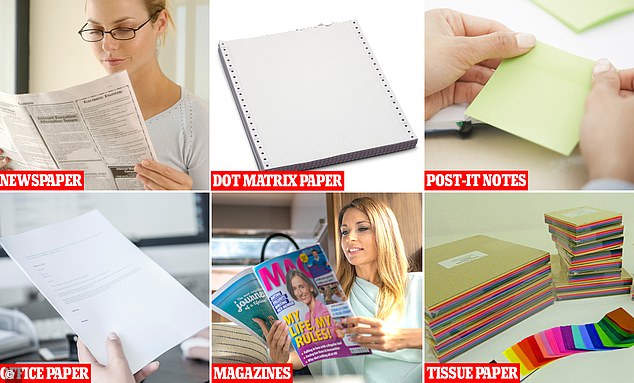

Using laboratory experiments, scientists have ranked 12 different types of paper based on how likely they are to cut into skin.

Two of them in particular pose the highest risk and are three times more likely to suffer a cut than the lower-risk types.

So do you have any in your home or office?

Thanks to their laboratory experiments, scientists have classified 12 different types of paper based on how likely they are to cut your skin. Do you use them in your home or office?

The researchers tested several different types of paper, including office paper, cards, magazines, and tissue paper.

According to scientists at the Technical University of Denmark (DTU) in Copenhagen, the two materials that need to be considered most are matrix paper and newspaper.

If you haven’t heard of the former, dot matrix paper is used in specific types of computer printers to create business reports, receipts, train tickets, and more.

“Paper has been central to human culture for more than a millennium,” said lead author Kaare Hartvig and colleagues at DTU.

‘However, its use is associated with a common injury: paper cut.

We found that paper with a specific thickness is the most dangerous.

Researchers had noted that most studies on paper cuts had focused on the risk of infection after cutting.

However, the “physical mechanism” that allows certain types of paper to pierce the skin better than others has been “poorly understood.”

“A particular mystery surrounds the link between paper thickness and the appearance of cuts, often described as unpredictable and erratic,” they said.

For the study, they tested several different types of paper against a plate of ballistic gelatin, a material designed to mimic human skin.

Paper types included tissue paper, book paper, shiny metallic paper, sticky notes, cards, and printed photographs.

Papers from two journal-like scientific journals (‘Science’ and ‘Nature’) were also analysed, as well as three brands of office printer paper.

Dot matrix paper (pictured) is used in specific types of computer printers to create business reports, receipts, train tickets, and more.

The experts also took into account the angle of each paper in relation to the skin at the time of cutting.

In general, excessively thin paper, such as tissue paper, tended to fold against the skin, preventing any type of injury, the researchers found.

Meanwhile, paper that was too thick distributed pressure over a large area upon contact and therefore generally could not be cut.

The most lethal papers were those that were neither too thick nor too thin, 65 micrometers or 65 millionths of a meter thick: that is, newsprint and dot matrix paper.

Both had a “tear probability” of 21 percent, about three times higher than photo paper (7 percent), Xerox office paper (6 percent) and tissue paper (4 percent).

“While tissues, books and photographs are generally safe, we cannot rule out certain risks associated with the use of office paper or magazines,” the team concludes.

And, in general, the cuts were deeper when they were made at an angle rather than head-on.

To demonstrate their findings, the team developed the ‘Papermachete’, a scalpel with a sheet of dot matrix paper that You can cut vegetables and meat ‘easily’.

But the tool is not suitable for “carving wood or spreading butter,” the researchers added.

The researchers also developed the ‘Papermachete’, a paper scalpel that can ‘easily’ cut vegetables and meat.

Close-up of the Papermachete sliding through a cucumber. The tool is not suitable for “carving wood and spreading butter,” the researchers add.

The team said their study – published in the magazine Physical Review E – ‘lays the groundwork for a physics-based design of paper-based blades’.

“In the future, paper manufacturers, printers and publishers could consider this during the product design process,” they wrote.

‘Despite its seemingly mundane nature, studying the physics of paper cuts has revealed a surprising potential use of paper in the digital age – not as a medium for the dissemination and storage of information, but rather as a tool of destruction.’