Among all the complex science surrounding climate change, one possible solution seems absurdly simple.

As basic as it may seem, scientists have built a giant vacuum cleaner to literally suck CO2 out of the air.

The huge plant in Iceland, nicknamed Mammoth, uses huge steel fans to suck in CO2, dissolve the gas in water and pump it deep underground.

At full capacity, Climeworks, the company behind the plant, says the vacuum cleaner will be able to extract 36,000 tons of CO2 from the sky each year.

While this is just a small fraction of global emissions, Climeworks believes bombs like The Mammoth are key to fighting climate change.

Scientists have developed a massive vacuum cleaner in Iceland to suck up to 36,000 tonnes of CO2 from the air each year.

Mammoth, as the plant has been called, uses 72 modular collection chambers to filter CO2 from the air using energy from a nearby geothermal power plant.

Construction on the Mammoth began in June 2022, but the plant has just been commissioned.

Its modular design allows the installation of 72 ‘collection containers’ that extract carbon from the air, although there are currently only 12 installed.

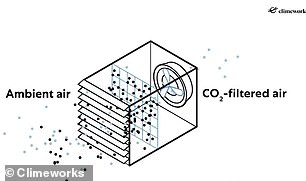

These use energy from a nearby geothermal power plant to drive large steel fans that draw ambient air from the atmosphere into special filters that trap CO2.

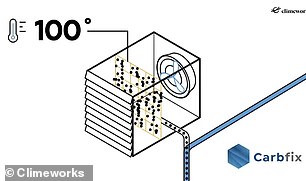

When the filters are full, they are sealed and the temperature inside the container rises to 100°C (212°F).

This frees the carbon from the filter so it can be removed by high-pressure steam jets.

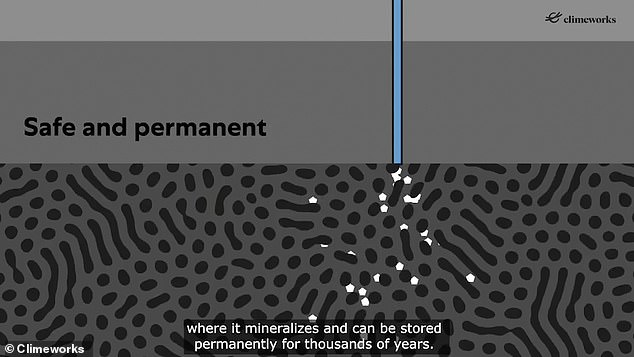

Like any carbonated drink, the gas dissolves in water to form a gaseous solution that is pumped deep into the volcanic rocks beneath the plant.

As water seeps to the surface, the CO2 reacts with the basalt and turns to stone over a few years.

Direct air capture works by passing ambient air through a series of filters (left) to trap CO2. These chambers are then heated and steam is injected to dissolve the CO2 in water (right)

The resulting mixture of CO2 and water is injected into the volcanic basalt beneath the plant, where it slowly turns into rock.

Last year, humans produced about 37 billion tons of CO2 by burning fossil fuels for energy.

Critics say the simplest way to reduce CO2 in the atmosphere is by reducing the amount of fossil fuels burned in the first place.

However, others point out that it takes time to transition to renewable energy and that some industries, such as steel production, can be very difficult to transition to.

For that reason, proponents of “carbon capture and storage” argue that we need plants like The Mammoth to give humanity a buffer while emissions fall.

According to the UN climate body, the world will need to remove between six and 16 billion tonnes of CO2 each year to prevent temperatures from rising by 1.5°C.

Climeworks says its plant (pictured) will be key to fighting climate change, providing part of the estimated 60 million tonnes of CO2 capture needed by 2030.

Currently only 12 of the 72 collection bins (pictured) are active, but the company plans to add more throughout the year.

Likewise, the International Energy Agency estimates that the world needs to store at least 60 million tons per year by 2030.

Mammoth is nine times larger than a previous carbon capture plant built by Climeworks in 2021 and is currently one of the largest in the world.

At its maximum capacity of 36,000 tonnes of CO2 per year, it could reduce global emissions by the equivalent of 7,800 gasoline cars.

However, that impressive figure is equivalent to only 30 seconds of the world’s annual CO2 emissions.

The technology behind ‘direct air capture’ has progressed rapidly, but is still held back by the lack of scale and cost of carbon capture.

Compared to reforestation, which can cost as little as £10 ($12.56) per ton of CO2 captured, direct air capture is extremely expensive.

The company is tight-lipped about exact costs, but executives said in a call to reporters that the cost is closer to £796 ($1,000) per ton.

However, the company aims to reduce that cost to £239 ($300) per tonne by 1030 and just £80 ($100) per tonne by 2050.

To keep its own carbon emissions low, The Mammoth’s huge fans are powered by geothermal energy from Iceland.

The plant is nine times larger than a previous plant created by Climeworks in 2021, which was the largest in the world when it was built.

Despite the enormous challenges facing carbon capture technology, Climeworks executives remain positive.

Jan Wurzbacher, CEO of Climeworks, says: ‘We started a long time ago (in 2009) in the laboratory. We had a small reactor the size of a cell phone and it captured a few milligrams of carbon dioxide.

“We’ve already come a long way and I think (Mammoth) is a very solid foundation for taking the next steps,” Mr. Wurzbacher said. The times.

Climeworks is currently working on a £40m ($50m) US government-funded facility in Louisiana that could capture one million tonnes of CO2 by 2030.

Climeworks sells carbon capture credits for around £796 ($1,000) per tonne and claims to have already sold 100,000 tonnes of CO2 capture credits to companies.

They are also not the only company to see carbon capture as a profitable opportunity, with many companies now looking to purchase carbon capture credits to offset their emissions.

Climeworks says it has already sold credits to offset the 100,000 tonnes of CO2 it aims to remove, although this would take about three years at full capacity.

The Stratos plant currently being built in Texas, for example, is designed to remove 500,000 tons of carbon per year.

Mr. Wurzbacher added: “Let’s look at the wind industry, even the oil and gas industry.”

‘Is there a history of humanity inventing a technical solution for something and then, within 30 years, scaling it up to a globally relevant scale?

‘The answer is yes, there are several antecedents. That is why we have shown as humans that we can do it.”