From sea turtles to elephants, migratory animals include some of the most iconic species on the planet.

They can travel thousands of kilometers depending on the time of year, often to reproduce, find food or simply survive.

Unfortunately, these incredible animals are at risk of being exterminated, and humans are the main culprit.

A new report warns that 22 percent of the world’s migratory species are threatened with extinction and that almost half at least are declining in number.

The two biggest threats to these animals are overexploitation and habitat loss, both resulting from human activity.

The new report names 260 migratory species (22 percent) as threatened with extinction, including the hawksbill turtle and the addax, an antelope with spiral horns.

The new ‘Status of the world’s migratory species‘ The report is published today by the Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals (CMS).

“Today’s report clearly shows us that unsustainable human activities are endangering the future of migratory species,” said Inger Andersen, executive director of the United Nations Environment Programme.

“Creatures that not only act as indicators of environmental change but play an integral role in maintaining the function and resilience of our planet’s complex ecosystems.”

Billions of animals make migratory journeys each year across land, rivers, oceans and skies.

They cross national borders and continents, and some travel thousands of miles around the world to feed and reproduce.

Migratory species play an essential role in maintaining the world’s ecosystems and provide various benefits, such as plant pollination and nutrient transport.

Pictured is social lapwing, an endangered migratory bird that breeds in Kazakhstan and winters in the Middle East, the Indian subcontinent and Sudan.

Other endangered migratory species include the European eel, which starts in the Sargasso Sea near Bermuda and crosses the Atlantic Ocean to Europe and then back.

The report was based on species datasets and contributions from institutions such as BirdLife International, the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) and the Zoological Society of London (ZSL).

The IUCN publishes its famous Red Listthe world’s most complete inventory of the global conservation status of biological species.

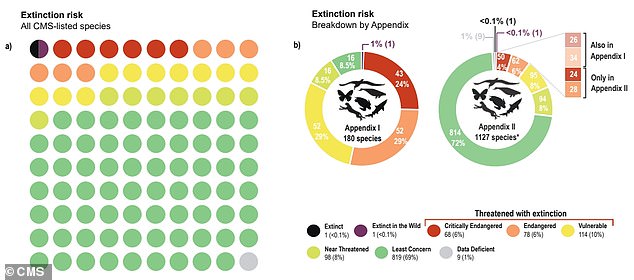

Of the 1,189 animal species recognized by the CMS as in need of international protection, 260 species (22 percent) are considered threatened with extinction, while 44 percent (520) show declines in their populations.

The 260 endangered animals have been assessed as “critically endangered” (68), “endangered” (78) or “vulnerable” (114) on the IUCN Red List.

Among them is the Hawksbill turtle, which stands out for its narrow, pointed beak and a distinctive pattern of overlapping scales on its shell.

This critically endangered turtle species is found throughout the world’s tropical oceans, primarily coral reefs, and has historically been hunted by humans.

Migrates long distances (typically 150 kilometers) between feeding grounds and nesting beaches.

Also threatened is the hammerhead shark, which is overexploited and prized for its fins by illegal traders.

The shark species is believed to migrate to deeper waters to find food until it reaches its adult size and eventually returns to its original location.

Critically endangered hawksbill turtles are found primarily in the world’s tropical oceans, primarily on coral reefs.

Conservation scientists consider the hammerhead shark (pictured) to be endangered.

As for terrestrial animals, the list includes the addax, an antelope with spiral horns native to the Sahara Desert.

It is believed to migrate south to the Sahel savannah zone of Africa during the hot season to find the first rains and rain-generated grasses.

Other endangered migratory species include the European eel, which starts in the Sargasso Sea near Bermuda and crosses the Atlantic Ocean to Europe and then back.

There is also the North Atlantic right whale, which was also hunted to the brink of extinction in the 1890s.

According to the report, man-made obstacles, such as bridges and roads, act as physical barriers to the migration of many of these animals.

This reduces the chances of successful migration, which in turn reduces the chances of survival.

Even “non-physical” barriers, such as disruptions caused by industrial development and maritime traffic, represent “formidable barriers to migratory populations.”

The addax is believed to migrate south to the Sahel savanna zone of Africa during the warm season to encounter the first rains and rain-generated grasses.

The North Atlantic right whale (pictured) was hunted to the brink of extinction in the 1890s.

Removing or mitigating physical obstacles to an animal’s migration, such as roads and bridges, vital to ensuring the survival of migratory species.

Of the 1,189 animal species recognized by the CMS as needing international protection, 260 species (22 percent) are considered threatened with extinction.

Other factors include pollution, including pesticides, plastics, heavy metals and excess nutrients, as well as underwater noise and light pollution.

In particular, the current situation of fish is of “particular concern”, with a whopping 97 per cent of CMS-listed fish species threatened with extinction.

Researchers say coordinated international action is “urgently needed” to reverse population declines and preserve these species and their habitats.

“The global community has an opportunity to translate this latest science on the pressures facing migratory species into concrete conservation actions,” Andersen said.

“Given the precarious situation of many of these animals, we cannot afford to delay and must work together to make the recommendations a reality.”