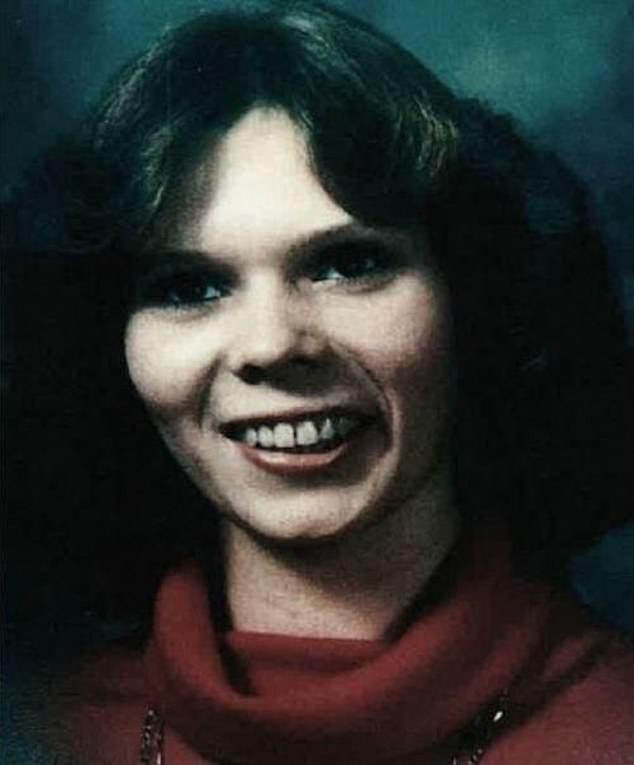

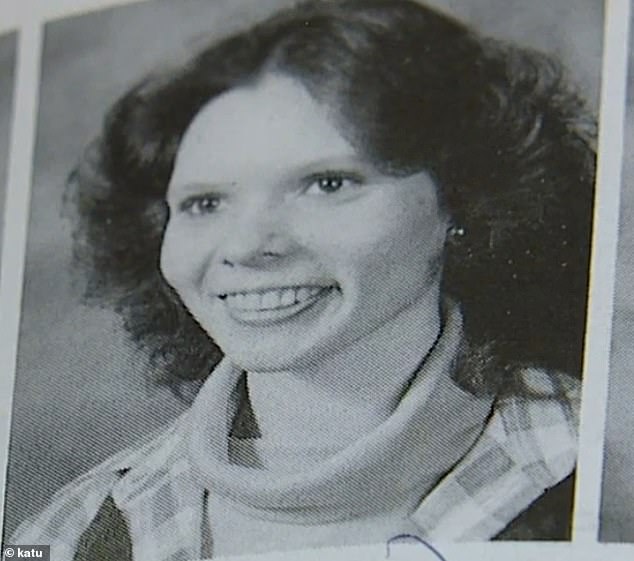

The murder case of a 19-year-old college student in Oregon was solved more than four decades later after DNA from a discarded piece of gum helped secure a conviction.

On Friday, Robert Arthur Plympton, 60, was found guilty of murdering Barbara May Tucker on the night of Jan. 15, 1980, as she walked across the campus of Mount Hood Community College.

Suspicions were raised when she never arrived for class. The next morning, students discovered her cold and partially naked body near a campus parking lot. There were signs that she had been sexually assaulted and that she had fought against her attacker.

A medical examiner determined the teen had been raped and beaten to death.

Friday’s ruling came after a three-week trial in Portland. According to The Oregonian, Tucker’s case was the oldest unsolved murder in the city of Gresham.

Robert Arthur Plympton, 60, was convicted of the murder of 19-year-old Barbara May Tucker in January 1980, when he himself was just 16 years old.

Tucker was headed to a night class at Mount Hood Community College but never arrived. Other students discovered her half-clothed body the next morning.

Decades passed before investigators were able to identify a suspect and make an arrest.

But advances in DNA sequencing technology have proven advantageous. In 2000, vaginal swabs taken during Tucker’s autopsy were sent to the Oregon State Police crime lab to develop a DNA profile.

In 2021, Parabon NanoLabs, a DNA phenotyping company, identified Plympton as “a likely contributor to the unknown DNA profile developed in 2000,” the Multnomah County Prosecutor’s Office said.

Plympton had a checkered criminal past, including a second-degree kidnapping conviction five years after Tucker’s death, according to the Oregon Department of Corrections.

Gresham Police Department detectives learned that Plympton was living in Troutdale and began monitoring him.

When Plympton spat a piece of gum onto the ground, they recovered it and submitted it to a state police crime lab.

“The laboratory determined that the DNA profile developed from the chewing gum matched the DNA profile developed from Ms. Tucker’s vaginal swabs,” the prosecutor’s office said.

This method of collecting DNA is similar to a step taken in the case of accused serial killer Rex Heuermann, where investigators compared DNA from a discarded pizza crust with evidence from the burlap used to link one of the Gilgo Beach murder victims.

The teen had been beaten to death and the medical examiner’s office determined she had been sexually assaulted.

Investigators began monitoring Plympton in 2021, after advances in DNA sequencing technology matched a sample from a discarded piece of gum to a profile developed in 2000.

Plympton was just 16 years old when Tucker was attacked and beaten to death.

Witnesses reported seeing her with a man the night of her murder, and several people recalled seeing her running down the street waving her arms, perhaps trying to call for help.

Plympton was arrested on June 8, 2021, while walking away from the home he shared with his wife and son.

He pleaded not guilty to murder charges at his arraignment that month.

There was no evidence that Plympton and Tucker knew each other, Multnomah County Assistant Prosecutor Kirsten Snowden said during the trial.

Multnomah County Circuit Court Judge Amy Baggio found the 60-year-old man guilty of one count of first-degree murder and four counts of “different theories of second-degree murder,” the county’s office said. prosecutor.

“To be clear, this court has no doubt that Robert Plympton beat Barbara Tucker in the head and face until she died,” Baggio said in court. ‘He did.’

Plympton was charged with rape and sexual abuse in addition to counts of first- and second-degree murder.

Despite evidence that Tucker had been sexually assaulted, Plympton was not convicted of these charges, as prosecutors failed to prove beyond a reasonable doubt that the abuse had occurred while she was alive.

During the trial, Plympton maintained his innocence, saying he did not match the description of a man seen dragging the victim into the bushes.

Defense lawyer Stephen Houze said there was “undoubted and unavoidable reasonable doubt” about the identity of Tucker’s killer.

He pointed to witness descriptions of the man who was seen with Tucker — who was nearly six feet tall — as being about his height or taller. Plympton’s booking records list his height as 5’9.

Houze also claimed that investigators never tested Tucker’s clothing for DNA evidence.

In a statement Tuesday, Plympton’s lawyers vowed to appeal the decision, saying they were “confident his convictions will be overturned.”

In 2021, after Plympton’s arrest, Susan Pater said she was troubled that her sister’s killer had lived nearby for so long.

Plympton was convicted of one count of first-degree murder and four counts of “different theories of second-degree murder.” He has not been convicted of rape or sexual abuse.

Two of Tucker’s relatives cried and hugged each other after the verdict was read.

His older sister, Alice Juan, said in a statement to the New York Times that her family was “delighted that this issue is finally resolved.”

“I thought it might not be the case as the years went by, but Barbie was a special little girl,” she said, describing Tucker as “bright, bubbly, caring, all those things.”

At the time of Plympton’s arrest in 2021, Susan Pater, one of Tucker’s three sisters, told KATU News that detectives had promised to hunt down the killer.

“I was totally surprised. It was amazing,” Pater said. “It was really good news. I had given up. Even though I think about her almost every night.

She said she found it difficult to accept that her sister’s killer had lived nearby for so long.

“That somehow it didn’t slip or come out of his mouth that someone could have done something, that he was able to move on with his life after taking another one. Yeah , it’s very hard,” she said.

“Could he sleep at night?” I have a feeling he probably could.

Plympton remains in custody at the Multnomah County Detention Center.

He is scheduled to be sentenced June 21 and faces a possible life sentence with the possibility of parole after 30 years for first-degree murder.