An investigation has discovered that a deadly ‘Franken drug’ sweeping Britain is advertised on X and Soundcloud.

Thousands of social media posts promoting nitacenes have been removed over fears they were fueling the spread of the powerful illegal drug.

It has been linked to more than 100 deaths in the UK, averaging almost three a week in recent times.

Following a BBC investigation In the Class A narcotic, the two social media giants removed several of these posts, but many lists still remained online.

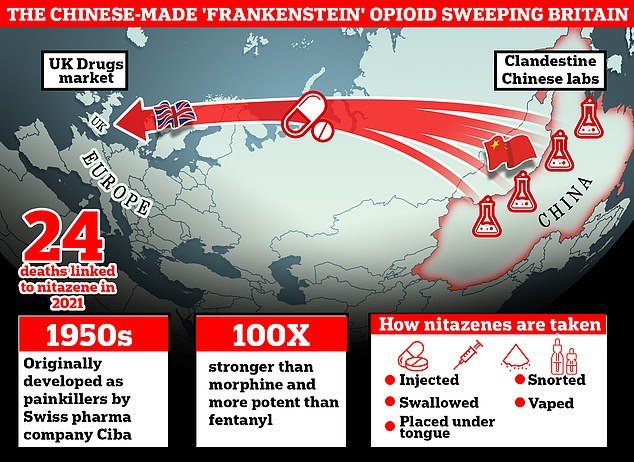

Chinese-made nitazenes have become popular with criminals and are being smuggled into the UK to be mixed with heroin and other illegal substances because they are cheap and addictive.

They are produced in laboratories and are several hundred times more potent than fentanyl, heroin and morphine.

Thousands of social media posts promoting nitacenes have been removed over fears they were fueling the spread of the powerful illegal drug.

Following a BBC investigation into the Class A narcotic, SoundCloud removed several of these posts, but many lists still remained online.

Nitacenes were originally developed as pain relievers by the Swiss pharmaceutical company Ciba in the 1950s, but never reached the market.

However, in recent years they have emerged among drug users in the United States, nicknamed “Frankenstein” opioids because of their great power.

It is believed to have formally arrived in the UK about three years ago, when the National Crime Agency first detected it among overdose patients.

Users often take them unknowingly when consuming other illegal substances, as traffickers seek to reduce production costs.

The BBC contacted 35 suppliers of the drug: 14 with advertising on SoundCloud, six with advertising on X and 15 through a website promoting wholesale chemical manufacturers.

After testing a variety of drugs in a lab, they found nitacenes in street heroin and black market anti-anxiety pills like Xanax and Valium, which traffickers had wrongly claimed to be.

Evidence suggests that dozens of suppliers are mailing nitacenes from China, where they are manufactured in laboratories, after having openly advertised them on the Internet.

Most ads contained the name and images of the drug, as well as contact details for secure messaging platforms and promises of safe shipping or customs clearance.

Many also offered bulk purchases for dealers to sell in small batches, rather than to individual drug users.

Some of these suppliers told the BBC that they would evade customs by disguising nitacenes in dog food and catering items.

Available in powder, tablet, and liquid form, nitacenes can be injected, swallowed, placed under the tongue, inhaled, and vaped.

When asked how they use SoundCloud to advertise their product, one vendor said, “It’s a music platform, but we can advertise on it.”

Available in powder, tablet, and liquid form, nitacenes can be injected, swallowed, placed under the tongue, inhaled, and vaped.

The drugs cause feelings of pain relief, euphoria, relaxation and drowsiness. But they can also cause sweating, itching and nausea.

Nitazenes mimic the effects of natural opioids, such as morphine, and are often combined with these medications, creating a deadly cocktail.

Two dozen deaths were linked to isotonitazene, a form of nitazene, in 2021 alone, according to data from the UK Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs.

Claire Rocha’s musical son Dylan was one of the first deaths linked to nitazene-tainted drugs in the UK.

Dylan’s band had been touring the UK before the Covid pandemic when he was found dead in Southmapton in 2021.

Ms Rocha described the recent findings as “shocking” and added that it was “absolutely crazy” that thousands of ads were being posted on SoundCloud and X.

She said: ‘How has that been allowed to happen? How many people have died because of what is announced there?

Charles Yates of the National Crime Agency said the rise in nitacenes is because the drug is cheap to produce, attracting criminals whose “sole motivation is greed.”

It also highlighted that the agency was working with police, Border Force and international partners to ensure “all lines of inquiry are prioritized and vigorously pursued to stop any supply of nitazenes to and within the UK.”

Last month, 14 nitacenes and another synthetic opioid were classified as Class A drugs under the Misuse of Drugs Act 1971, meaning anyone who possessed them could be sentenced to seven years in prison or an unlimited fine.

Nitacenes were originally developed as pain relievers by the Swiss pharmaceutical company Ciba in the 1950s, but never made it to the market.

Home Secretary James Cleverly said the ban had adopted a generic definition of nitacenes to cover any new medicines emerging in the future.

He said: ‘We are very alert to the threat of synthetic drugs and have been taking a number of preventive measures, learning from experiences around the world, to keep these vile drugs off our streets.

‘Our plan is working – the total quantities of synthetic opioids arriving in the UK remain lower than other countries – but we are not complacent.

“Placing these toxic drugs under the strictest controls sends a clear message that the consequences of their sale will be serious.”

According to the Ministry of the Interior, an “intensive operational effort has been made to locate [nitazenes] and their suppliers: on the streets, at the borders and online.

He also made clear that tech companies “must do more to quickly remove this type of content… and prevent users from being exposed to it” to align with the Online Safety Act, which became law last year. .

When suppliers were asked why they were providing an illegal product, only six responded and all stated that they had never shipped anything to the UK.

SoundCloud told the BBC it was “being targeted by bad actors” and vowed to do “everything we can to tackle this global epidemic.” The website also removed nearly 3,000 posts.

MailOnline has contacted SoundCloud and X for further comment.