After decades of disputes over the fate of the Chagos Islands and the key US-UK military base they house, the British government has reached an agreement to hand over sovereignty of the archipelago to Mauritius.

Diego Garcia Atoll, the largest of the islands, covering only 10 square miles of mainland, serves as a strategically important base for Navy ships and long-range bomber aircraft.

Since the island’s population was exiled in the 1960s, and foreign military personnel took their place, few have been allowed access to its shores, allowing rumors to arise about what happens there.

Walter Ladwig III, professor of international relations at King’s College London, told the bbc that while the base serves “many important functions,” the level of secrecy surrounding it “seems to go beyond what we see elsewhere.”

About 1,000 miles from the nearest landmass, with no commercial flights allowed to land and those who want to set foot on the island needing a permit, very few have been allowed to stay there.

Journalists have been banned for decades, and one was even kicked off its shores by “hostile” British officials after pretending his ship ran into trouble. “Go away and don’t come back,” they told him as they escorted him away.

For the first time, US and UK authorities recently granted journalists permission to stay on Diego García, allowing them a glimpse of what life on the island is really like.

The British Indian Ocean Territory (BIOT) or Chagos Islands. The largest island in the archipelago is Diego García.

The US Naval Construction Battalion, known as the Navy ‘Seabees’, bathes in the Diego Garcia pool in a 1981 file image.

The island paradise is home to British and American troops and foreign contractors, and the cultural influences of both are said to be evident throughout.

The entrance to the base’s airport terminal is reportedly decorated with Union Jacks and photographs of British figures such as Winston Churchill.

There is also a nightclub called Brit Club, which has a bulldog as its logo, while patriotic street names include Britannia Way and Churchill Road.

There are British police cars present, but they drive on the right side of the road, with the dollar being the accepted currency.

There is said to be a cinema, a bowling alley, a fast food restaurant and even a gift shop selling Diego García souvenirs, despite the lack of tourists.

Most of the staff living on the island are American, and there is said to be only a “token British presence”.

The island was leased by the United Kingdom to the United States in 1966 for an initial period of 50 years, before it was extended, and was to expire in 2036, before the latest agreement.

The new agreement with Mauritius will guarantee the rights of the two countries to operate the military base for at least the next 99 years.

The 1966 agreement had multiple advantages for Britain: it was able to strengthen its military ties with the United States, providing one of its key allies with an important base on a major international trade route.

Its position meant it later proved pivotal to US air operations during the Gulf War and the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, with aircraft sent directly from the island during the “war on terror”.

As part of their secret deal, in exchange for the use of the island, the United States agreed to give the United Kingdom a $14 million discount when it purchased its Polaris nuclear missiles.

Aerial image showing roads, buildings and forests on the Diego Garcia Islands in the Indian Ocean

Official First Day Stamps of the British Indian Ocean Territory ‘Ships of the Islands’ 1969

A 1966 Foreign Office memo stated that the goal of their plan “was to get some rocks that will remain ours; there will be no indigenous population except seagulls.’

They considered multiple options but settled on Diego Garcia as the “prime location” due to its strategic position in the middle of the Indian Ocean, as well as its lack of a large population.

But for the more than 1,000 people who lived there, the decision was devastating.

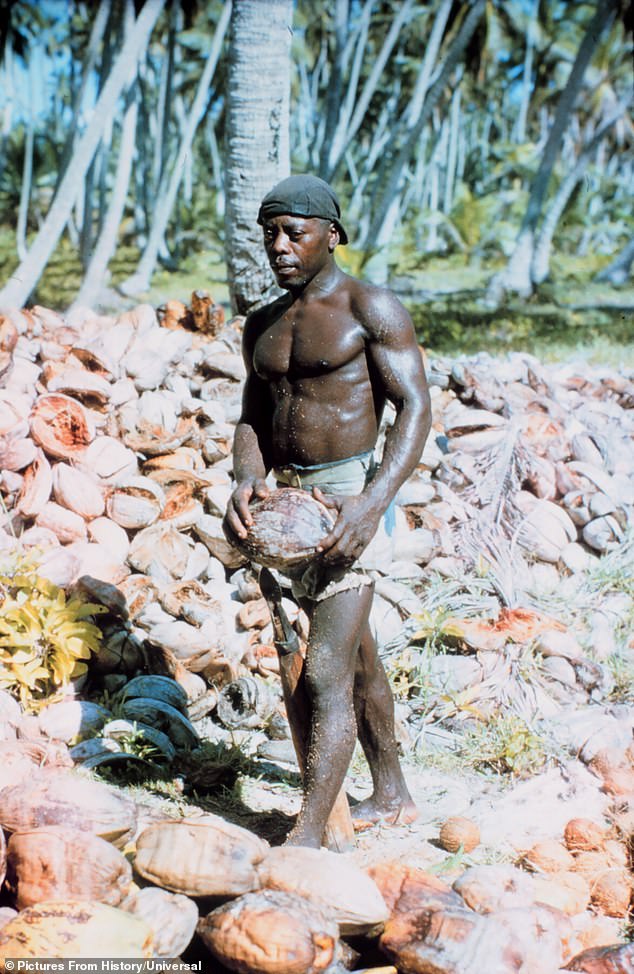

The islands were uninhabited until the late 18th century, when the French established coconut plantations and brought slaves from Madagascar and Mozambique to work them.

At Diego García the ruins of the plantations are preserved, with wandering wild donkeys described as a “ghostly remnant of the society that had been there for almost 200 years”.

During that time, emancipated slaves and their descendants, known as Chagossians, built their own communities and with them developed a distinct language and culture.

More than 1,000 people lived in Diego García before it was taken over and converted into a US and UK military base.

Undated image released by the US Navy showing an aerial view of Diego Garcia.

The islands, which were British Indian Ocean territories from 1814, were described by their inhabitants as a happy and abundant place to live, where “everyone had a job, their family and their culture.”

But in 1973, the Chagossians were forced to leave the central Indian Ocean territory to make way for the military base, and many of them were sent to Mauritius or the Seychelles.

The expulsions are considered one of the most shameful parts of Britain’s modern colonial history and Chagossians have been fighting to return to the islands for decades.

Mauritius became independent from the United Kingdom in 1968 and has maintained that the islands belong to it ever since.

For decades, the small island nation struggled to gain international support, but in 2019, the UK’s claim to sovereignty was declared illegal by the UN’s highest court, which told Britain it had to return the islands as soon as possible. possible.

Under the new treaty, Mauritius will now be able to implement a resettlement program on the Chagos Islands, while accepting the use of Diego Garcia as a military base.