New blood tests could help doctors diagnose Alzheimer’s disease more quickly and accurately, a new study found.

Alzheimer’s disease is the most common form of dementia, affecting 6.7 million Americans. With the aging population in the United States on the rise, that number is expected to rise to 13 million by 2050.

A study of 1,213 patients in Sweden between February 2020 and January 2024 published Sunday found that blood tests focusing on a form of protein called tau were far more accurate at diagnosing the disease than doctors alone.

In the study, patients who visited a primary care doctor or specialist for memory problems received an initial diagnosis through traditional testing, donated blood for testing, and were sent for a confirmatory spinal tap or brain scan.

The initial diagnosis by primary care physicians was 61 percent accurate and that by specialists 73 percent accurate, but the blood test was 91 percent accurate, according to the findings of the Lund University researchers.

A new study found that blood tests focusing on a form of protein called tau were much more accurate at diagnosing the disease than doctors alone

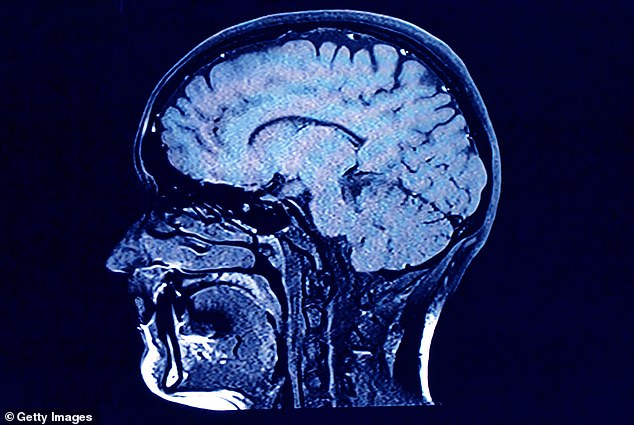

Scientists believe that Alzheimer’s is likely the result of an abnormal buildup of proteins (amyloid and tau) in and around brain cells.

“Not long ago, measuring pathology in the brain of a living human being was considered simply impossible,” Dr Jason Karlawish, co-director of the Pennsylvania Memory Centre at the University of Pennsylvania, who was not involved in the research, told the BBC. The New York Times.

‘This study adds to the revolution that has occurred in our ability to measure what happens in the brains of living human beings.’

Although the root cause of Alzheimer’s disease is still debated, scientists believe the damage is likely the result of an abnormal buildup of proteins (amyloid and tau) in and around brain cells.

In Alzheimer’s patients, amyloid proteins are not removed from the body efficiently and end up forming plaques in the brain. Tau proteins break off from neurons and form tangles.

Both can cause neurons to die, making it difficult for signals to be sent throughout the brain.

Blood tests measure a form of tau that correlates with the amount of plaque buildup in a person, said Dr. Suzanne Schindler, a neurologist at Washington University in St. Louis.

A high level indicates a high likelihood that the person has Alzheimer’s, while a low level indicates that Alzheimer’s is probably not the cause of the memory loss.

Experts say blood tests should be limited to use by doctors and researchers only, and not be widely available to the public.

They should only use blood tests that have been shown to have an accuracy rate greater than 90 percent, said Maria Carrillo, chief scientific officer for the Alzheimer’s Association.

The Alzheimer’s Association is working on guidelines, and several companies plan to seek FDA approval, which would clarify appropriate use.

Testing is not for people who don’t have symptoms unless it’s part of enrolling in research studies, Schindler said.

Alzheimer’s disease is the most common form of dementia, affecting 6.7 million Americans.

This is partly because amyloid buildup can begin two decades before the first sign of memory problems appears, and so far there are no preventative measures other than basic advice to eat healthy, exercise and get enough sleep.

There is currently no cure for Alzheimer’s, and new drugs in development such as donanemab (a pill taken twice a day that may reduce levels of a damaging brain protein called amyloid) only marginally slow the rate of progression and have dangerous side effects such as bleeding in the brain.

While the drug was hailed from the start as a potential therapy, a quarter of patients in the trial suffered brain inflammation and three people died from brain swelling or bleeding attributed to the drug.

Another drug, Leqembi, works in a similar way to donanemab but can also cause amyloid-related imaging abnormalities (ARIA), which are brain changes that can include bleeding and swelling.

It is FDA approved, but studies show that about 20 percent of people taking the drug develop ARIA, but only 20 percent of those people experience symptoms.