A grandmother who was scammed out of $1.6 million by a man with a “posh British accent” posing as an ING employee has called on banks to refund victims of the scam.

Last November last year, Harriet Spring was approached by a man called ‘George’ who told her he worked at her bank, ING, and asked if she was interested in good interest rates on fixed deposits.

The call came at a moment of weakness for Ms Spring, who was otherwise worried about moving her 95-year-old mother to a care home on the New South Wales south coast.

“It was the end of a very difficult year and this guy made it very easy,” Mrs. Spring told ABC.

The architect, from Canberra, spoke with ‘George’ for several months but the alarms never sounded because what he offered “was nothing crazy, nothing too out of the ordinary.”

“So I didn’t think, ‘That sounds too good to be true,'” Ms. Spring added.

He finally handed over $1.6 million: his mother’s life savings.

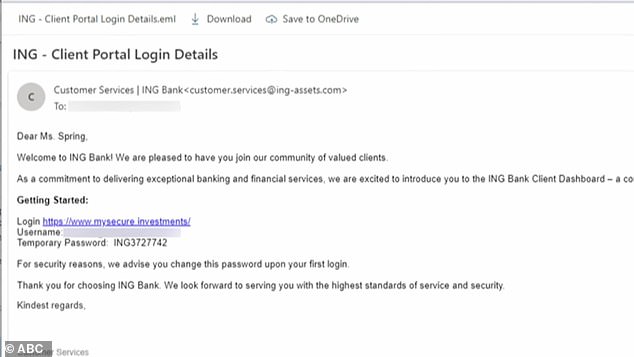

“It didn’t sound dodgy in any way, you know, all the emails were branded ING… I was completely fooled,” Ms Spring said.

“I was so relieved that I could finally put everything behind us and we could sit down and focus on mom.”

ING was not involved in the process and the scammer used convincing but fake email signatures.

The money was eventually transferred to a Westpac account before being funneled to a dozen other Australian bank accounts where it could not be traced.

Ms Spring’s requests for information have been rejected for “privacy reasons”.

Harriet Spring (pictured) was approached by a man called ‘George’ in November last year, who told her he worked at her bank, ING, and asked if she was interested in good rates for fixed deposits.

The call came at a moment of weakness for Ms Spring, who was otherwise worried about moving her 95-year-old mother (pictured) into a nursing home. She eventually lost all of her mother’s life savings.

Westpac declined to comment on individual cases but said preventing scams was one of its “highest priorities”.

“When customers of other banks transfer money to fraudsters, we work hard to recover funds on their behalf wherever possible,” a spokesperson said.

Unfortunately, Spring’s experience is not unique and it is not the first time victims have been attacked by men with posh British accents.

An Australian businessman was scammed out of $130,000 in a sophisticated text message scam by a man with a British accent.

Australians lost $2.7 billion to fraud in the last year, according to the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC).

This is a marginal decrease from the record $3.1 billion lost in 2022, but still higher than the figure from two years earlier.

Consumer Action Law Center executive director Stephanie Tonkin said Ms Spring’s story was a common one.

“Our lawyers hear reports every day of people who have been deceived by very complicated and sophisticated scams,” he told the program.

‘These scammers are no longer people in your basement.

‘These are people who work for multinational companies with resources and the ability to use technology such as AI (artificial intelligence) to cheat people out of their money.

“In many cases, it is almost impossible to detect a scam and therefore almost impossible to protect yourself.”

“It didn’t seem dodgy in any way, you know, all the emails were branded ING… I was completely fooled,” said Mrs Spring (pictured: part of the correspondence with the scammer).

Mrs. Spring has been left with the feeling that she can no longer trust anyone.

He renewed his calls for Australian banks to refund scam victims and shared a petition on social media urging governments to implement “strong rules requiring businesses to detect and prevent scams, and require banks to refund to the victims”.

‘Everyone can be scammed and this Government is behaving as if banks matter more than their constituents!’ Ms. Spring wrote.

The legislation would bring them in line with UK banks that have signed up to a voluntary reimbursement code since 2019, which will become mandatory in October.

“You should be assured that your money is kept safe and if it is not, you should be refunded,” Ms Tonkin added.

“We (consumers) simply don’t have information or access to information like unusual transactions, like mule account details, we don’t have the information to be able to protect ourselves.”