Sworn to secrecy by the Imperial Japanese Army, Hideo Shimizu carried the horrors he saw at the famed Unit 731 facility with him for more than 70 years.

The 93-year-old was just 14 when he was recruited as a cadet in the city of Harbin, in what was then Japanese-occupied Manchuria, during World War II.

There, he was groomed to participate in some of the worst atrocities in history: human experiments conducted on prisoners of war, including pregnant women and young children.

More than 3,000 people – mostly Chinese civilians, but also Russian, British and American prisoners of war – were dissected alive, infected with the bubonic plague and used as human guinea pigs for frostbite treatments in nightmarish torture laboratories.

Decades later, innocent photographs of his grandchildren and great-grandchildren reminded Shimizu of the faces of the many victims he encountered in the slaughterhouse.

Hideo Shimizu, now a great-grandfather, has revealed the horrors he saw as a member of Unit 731.

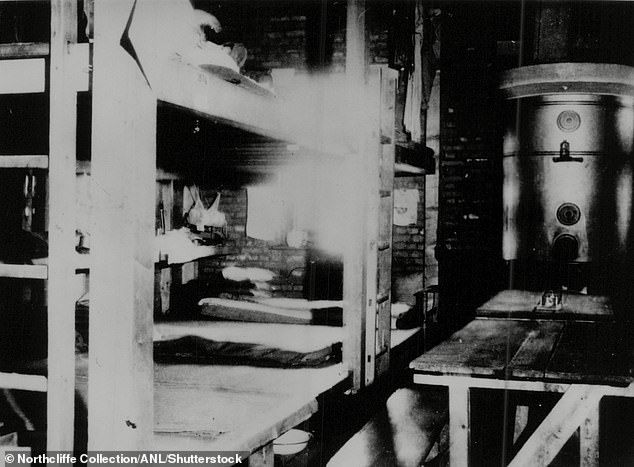

Personnel from the puppet state of Manchukuo conducting bacteriological tests on infants and young children, led by Japanese Army Unit 73, in November 1940.

A human ‘subject’, apparently a young Chinese civilian, is subjected to an unknown form of bacteriological testing in Unit 731

Hideo Shimizu, center, in 1945 when he was a teenage cadet who had just been recruited into Unit 731.

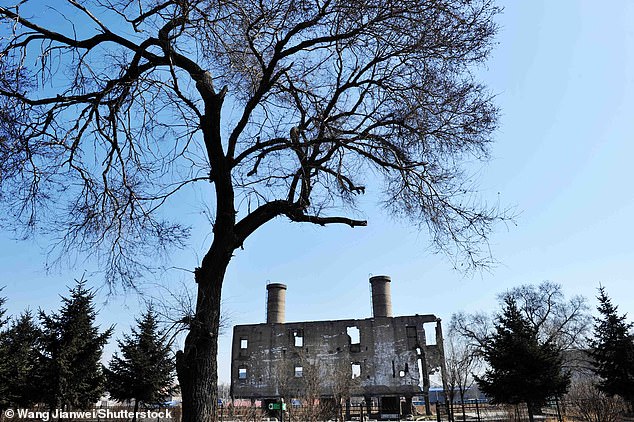

The ruins of one of Japan’s germ warfare facilities during World War II in the northeastern Chinese city of Harbin.

The veteran realized he had to break his silence for the sake of the next generation.

Shimizu, now a retired architect who built a comfortable life for himself and his family, tried to bury his dark past, without even revealing it to his closest relatives.

But memories of his previous life came flooding back when he and his wife visited a war museum in 2015.

He couldn’t contain his emotions when he saw a photo among the relics of a large brick building: the Epidemic Prevention and Water Purification Department of the Kwantung Army, or Unit 731.

He found himself telling his wife everything he knew about the building and eventually admitted that his knowledge was firsthand, as he himself had been a member of the biological warfare unit.

Unit 731 was built in 1936 in present-day Harbin, northeast China, for the Imperial Japanese Army to conduct research on germ warfare, weapons capabilities, and the limits of the human body.

The undercover operation was initially carried out under the guise of a sawmill and then a water purification plant.

Although what the sick scientists were cutting was human flesh and not wood, they dehumanized their victims by referring to them in Japanese as ‘marutas’ or wooden logs.

‘Many ‘marutas’ died and Japanese soldiers were also dissected. I often wondered why Unit 731 had done so many bad things. Shimizu said.

An aerial image shows the camp, which housed prisoners of war on whom experiments were carried out.

Plague patient’s wound during bacteriological test conducted by Japan’s Unit 731

Shimizu was called upon to bury the burned bones of murdered inmates in an effort to conceal the unit’s crimes. In the photo: Excavating in Unit 731

He was drafted into the unit’s ranks in late March 1945, just months before the war ended, to serve as a “technician on parole.”

An image remains of Shimizu as a teenage cadet in uniform alongside his comrades when he joined.

His former teacher had encouraged him to take up work because of his aptitude for arts and crafts.

“I didn’t know anything about what the military was or what it specifically did,” he said in a recent interview.

He expected to be sent to a factory, but instead, he and five other children from his village were sent on a train to China to begin working in Unit 731’s laboratories.

He says he still has nightmares about the day in July 1945 when he was taken to a display room inside the auditorium on the building’s second floor.

The room was filled with jars, he said, some as tall as an adult, each containing human body parts preserved in formalin.

“There were some that had been cut in two vertically, so that their organs could be seen,” Shimizu said.

The image shows some of the facilities of the famous germ testing ground.

The image shows the inmates, known as ‘maruta’, which means logs, and the guards at the extermination camp.

‘There were children; ten or twenty of them, maybe more. I was stunned. I thought, ‘How could they do this to a little boy?’

It was Shimizu’s first time seeing dead bodies and he couldn’t stop crying, while the person who took him on the tour didn’t say anything.

‘I think they took me there because they wanted to see my reaction to seeing the logs. All she could think was, ‘What are they going to make me do?’ he said.

Shimizu soon realized that he was being trained to perform the dissections himself.

Fortunately, the child soldier was saved by the course of the war, which would end abruptly weeks later with Japan’s surrender.

Three days after the atomic bomb was dropped on Nagasaki, Shimizu was called to the camp’s prison, morbidly nicknamed the “log cabin,” to bury the burned bones of prisoners killed in an effort to conceal the unit’s crimes. .

Soviet forces invaded former Manchuria in August and he and other members of the unit retreated to Japan.

Soldiers and technicians were given a cyanide compound and ordered to commit suicide before being captured.

After returning to Japan, Shimizu never spoke of what he saw or heard in the death camp.

Today the site, now a museum, echoes many of the chilling features of a former Nazi death camp with its disused railway tracks and ghostly buildings.

The ruins of one of the germ warfare facilities, with two large chimneys.

A woman visits the ruins of one of Japan’s germ warfare facilities during World War II.

The site of Japanese Unit 731 in Harbin, which opened to the public to mark the 70th anniversary of the end of World War II.

One structure still today contains rows of cages that housed giant rats that Japanese doctors used to combat the bubonic plague.

The horrendous disease was later unleashed on hundreds of thousands of Chinese, by dropping plague-carrying fleas on villages as part of biochemical warfare experiments.

Photographs in the book Unit 731: Devil’s Laboratory, Eastern Auschwitz show Japanese soldiers participating in vivisection, performing operations on a living person to study living tissues and organs.

Despite overwhelming evidence of the Imperial Japanese Army’s crimes – as well as cover-ups by the United States and others – many in Japan still refuse to believe Shimizu.

He received insults online from right-wing nationalists who refused to accept that Japanese troops could have behaved in such a disgraceful manner.

“This old man is telling lies… Either that, or he doesn’t exist,” wrote one conspiracy theorist.

Responding to his claims, Shimizu said The Asahi Shimbun newspaper: ‘You don’t know the horrible things Japan did to the people of another country.

“No matter what people tell me, I must continue to tell the truth, otherwise future generations will be deprived of the opportunity to know.”