Sumina Kumal was 12 years old when she had her first period at a relative’s house.

At her mother’s insistence, Sumina isolated herself in a room for days because she feared what the neighbors would think if she let her daughter do whatever she wanted.

And for three days she sat there.

“They wouldn’t let me go out to see the sun and it was winter. I couldn’t stand it, so I rebelled against my mother and went out to see the sunlight.”

Now Sumina has learned to cope with the situation by seeing isolation as “three days of rest” and “dissociates” herself from the idea that her parents insist on continuing this custom.

But this is not an isolated incident.

Sumina Kumal was just 12 years old when she was first isolated in a room for days during her period.

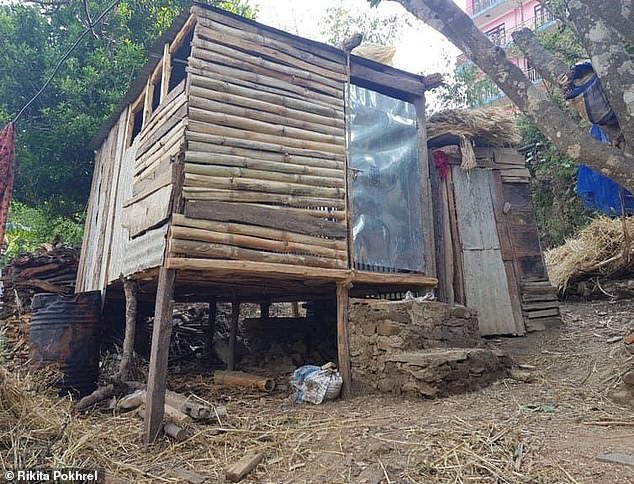

These menstrual huts are usually made of mud or wood and are located kilometers from the main house.

It is a Nepalese cultural practice known as Chhaupadi, a menstrual taboo that prohibits women and girls from participating in normal daily activities during their menstrual cycle.

I traveled to Nepal and was shocked by the reality that these women and girls have to face.

Having your period means that you can create a new life and it is considered the time to become a woman. However, in Nepal, having your period has always been associated with moral corruption and evil.

Rikita Pokhrel, 19, said she was isolated for seven days in the corner of a room during her first period.

He had to sleep on the floor with a different set of sheets and had to follow strict rules outside of confinement.

Rikita told FEMAIL: “For the first three days, we are not allowed to enter the kitchen, cook for our family or touch the food being prepared. We are also not allowed to go to the temple.”

Menstruating women and girls are considered to be the manifestation of bodily impurity. It is also widely believed that contact with a menstruating woman can contaminate food, people, and religious icons.

The reign of a Kumari, hand-picked when she is three to four years old, is symbolic of this practice.

Rikita Pokhrel said she wants to dismantle period taboos and wants to study psychology; she would also like to advocate against strict curfews and gender discrimination.

I went to one of the Kumaris’ palaces twice, and both times I was stunned by the reverence they showed her and the controlled look on such a childlike face.

Kumaris are selected after a series of tests (one of them passes 32 physical perfections such as having a “lion’s breast”) before being sent to various palaces, known as Kumari Ghar, to become the living incarnation of the Hindu goddess Taleju.

When I was in Kathmandu, I saw the Kumari twice. She was a young girl with painted face, adorned with jewels and fine clothes.

She stood on the balcony with a straight face as we bowed and said “namaste.” Then, after 20 seconds, she ducked inside and we were escorted out of the palace with the door chained behind us.

Every physical action the Kumari performs is interpreted as an omen. If she smiles at you, it means you will die soon. If her feet touch the ground outside the temple, it means an earthquake is coming.

That power is literal and they treat her with the utmost reverence, providing the living goddess with a life of luxury.

Until her first period.

It is believed that once the goddess bleeds, she leaves her body and is expelled from the temple with the expectation that she will live out her life as a nun. The Kumari’s family receives compensation equivalent to between $80,000 and $90,000.

Rama Rama, a Nepalese guide at Basantapur Durbar Square in Kathmandu, where one of the nine Nepalese Kumaris resides, said: “She is a spiritual guru, a spiritual guardian. She removes obstacles in life, but only before menstruation. After menstruation, she loses her goddess powers.”

I met Rikita, Rejina and Sumina at a Girls’ Empowerment Program panel in Nawalpur, Nepal.

Tourists have the opportunity to see the Kumari in Kathmandu’s Basantapur Durbar Square, but after she appears, we are escorted out of the palace square and the gates are closed behind us with a chain.

When I pressed him to explain why menstrual periods are considered impure, Rama Rama said, “It is natural. Before menstrual periods, women are innocent. She represents the Earth and the Earth is virgin, so she is a virgin power. A supernatural power.”

Menstrual taboos are passed down from generation to generation, mainly through grandmothers and mothers who experienced the same periods.

Rikita said: “It is women who come to me and tell me that this is our tradition, that these are our rules, that this is what our ancestors gave us, so we must follow it.”

On a night out in Kathmandu, I met Yozana Thapa, a comedian who said she often uses the discrimination faced by women in Nepal as material for her performances.

Yozana said her generation is leading the way in dismantling menstruation stigmas, but it is often difficult to change the minds of older generations.

“It’s hard to convince your family. There comes a point where you give up because they’re not going to change, so I’ll just wait for them to die.”

The community enforces the chhaupadi law. In religious places and temples, if word gets out in the neighborhood that a woman who attends them is on her period, she will be ostracized and ridiculed.

Rikita said: ‘People will talk badly about you behind your back or make fun of you during mass. If society finds out, they will ask where this generation is going. What are they learning from our ancestors?’

“They’ll say she’s being a leader. They’ll say she’s doing bad things. They’ll try to stop her growing up, or they’ll stop everything she’s done or what she’s doing with her life.”

The Girls Empowerment Program is currently building a center in Nawalpur

In Nepal, girls have died in ancient menstrual huts from snake bites, overheating, hypothermia and animal attacks.

Some girls have managed to dismantle Chhaupadi. Rejina Gharti, a 20-year-old women’s rights advocate, said: “I tried to end this stigma in my own home first, before campaigning in society and the community so that I could reach out to other people.”

At Rejina’s house, she told me, she has free rein to use the kitchen and is not obliged to isolate herself. The only barrier to entry is the temple.

During Tihal in Nepal — a five-day Hindu celebration in late October — Rejina used her homemade sanitary pads to hide from her mother that she was on her period.

But on the second day, she bled.

‘When I said I was going to take a bath because I was bleeding, my mother said, “Then you can’t give your brothers tikka. You can’t celebrate the festival.”

Rejina responded with the only legal loophole she knew: in Nepal, one can worship at the temple on the seventh day of a woman’s menstrual cycle.

Rikita used scientific evidence to debunk the stigmas surrounding menstruation in her family.

It is widely believed throughout the country that if a menstruating woman touches a plant or vegetable, it will rot, so she decided to conduct an experiment using flowers on the second day of her mother’s period.

In my last days in Nepal, I met Rejina at another organization: she was getting a visa to travel to a conference in Bangkok to present business ideas about creating sustainable clothing made from hay.

Most girls in Nepal do not stay in menstrual huts, so they are locked in their rooms or have to stay at a relative’s house to avoid seeing their parents and siblings.

Rikita was 16 years old when they went out to their garden to plant the flowers they had bought at the market. After a few days, Rikita’s flowers died while her mother’s flowers bloomed.

Rikita showed her grandmother her mother’s flowers and got a surprising reaction.

“I don’t know what happened that day, but when my grandmother saw the results of the experiment, she started to show a little solidarity. She understood what I was trying to tell her.”

Rikita said that after that day she was given the freedom to move around her house before the seven-day restrictions ended.

“I can go anywhere I want, I can talk to my parents and even eat whatever I want.”

Rikita, Yozana, Rejina and Sumina said they will not continue this practice with their children.

Rikita said, “Menstrual taboos are not the only thing we need to change. There are many things in our society that need to be worked on. So, I will continue to work on that in the future.”