Table of Contents

Learners are travelling almost twice as far to take a driving test than they did before the Covid-19 pandemic and huge delays for available testing slots have created an endless backlog for budding motorists, new research has found.

With the Driver and Vehicle Standards Agency (DVSA) failing to clear the huge backlog of learners, prospective drivers must take matters into their own hands to secure a place on their practical test as soon as possible.

For one young driver, this meant traveling a staggering 400 miles to avoid waiting months for a reservation where he lives, the study found.

After an in-depth analysis of more than six million driving test records, Marmalade found that learners could end up having to travel up to 25 miles (24.49) on average for a test in 2030, a 194% increase from 2019.

Several freedom of information requests to the DVSA by car insurance company Marmalade over a six-month period revealed that learners travelled 48 per cent longer to take their driving test in 2023 compared to 2019.

The average distance traveled from home to a testing center was 12.33 miles in the most recent full year (2023), compared to 8.33 miles in 2019.

And the situation does not seem likely to improve in the near future.

After an in-depth analysis of more than six million driving test records, Jam It found that students could end up having to travel up to 25 miles (24.49) on average for an exam in 2030, an increase of 194 percent from 2019.

This represents an annual increase of 10.3 percent.

Mark Steeples, a driving instructor at Pass Mark driving school, said it was “quite shocking” that learners could soon have to travel an average of 25 miles just to take a test.

“I am surprised by the yearly increase in the distance travelled for a test, but I guess it shows how desperate people are to learn to drive and will do whatever it takes to achieve it.”

Gap between North and South in availability of driving tests

The data also shows that a geographical gap has opened up: students in the south of England have to drive much further to take an exam than those in the north.

In 2023, students in the Southeast traveled the furthest, 22.4 kilometers, while those in the Northwest traveled 11.4 kilometers on average, almost half the distance.

Unsurprisingly, London is seeing the biggest increase in the number of remote students forced to travel to take an exam – up 7.7 miles in 2019 and up to a massive 17.7 miles in 2023.

This represents a staggering increase of 130.77 percent, with an average growth of 23.25 percent each year.

A similar pattern of growth is shown in the Southeast and East, which report year-on-year growth of 21.2 percent and 12.95 percent respectively.

Students in these three regions are finding it increasingly difficult to pass a driving test after hours of hard work preparing for their practical test.

In total, a higher than average distance was travelled to reach 164 test centres across the UK in 2023, as test centre locality and availability of test spaces decreases.

Some 34,614 students made a trip of more than 100 miles.

Mark says he has received inquiries from people wanting to travel further afield to get tested.

‘I’ve had enquiries from people wanting to learn and sit a test about 50 miles from my home. Why go to an area you don’t know? Taking a test is hard enough anyway, you have your whole life to drive on UK roads, but don’t choose the day of your driving test to do it.

‘Many instructors only teach test routes in the local area, but that means most students will not be prepared for any test routes and the potential impacts of driving in a new place.’

I drove 400 miles to take my driving test.

Kayla Van Dorsten drove from Surrey to Cornwall to get her licence.

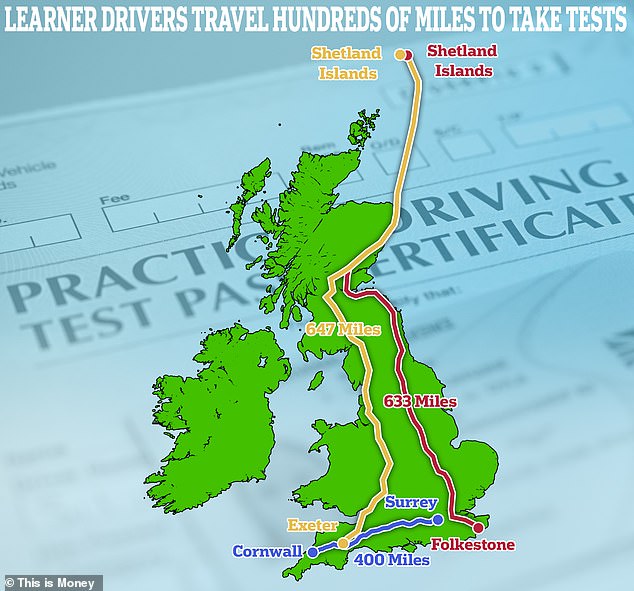

One student, Kayla Van Dorsten, found it so difficult to reserve an available driving test spot near where she lives that she resorted to traveling 400 miles to beat a six-month wait list at her local centers.

The 18-year-old drove from Surrey to Cornwall to get her licence because she needed to be able to drive herself to university.

“I was already nervous about taking the driving test, but being in an unfamiliar area posed new obstacles to overcome,” she explained.

‘There were different speed limits to the local routes I had practised on and also other road users I was unfamiliar with, such as tractors.

“Taking the exam four hours away meant I had to stop studying for two days and pay for accommodation and petrol to get to the exam centre. It was very inconvenient, but I needed to get my licence as soon as possible because I could no longer rely on public transport due to the strikes to get to university.”

And Kayla is not the only one…

In 2023, one student travelled a staggering 647 miles from Exeter to Shetland to take their practical test, while another travelled 633 miles from Folkestone to Shetland.

DVSA centre in Lerwick, Shetland. In 2023, one learner travelled a staggering 647 miles from Exter to Shetland to take their practical test, while another travelled 633 miles from Folkestone to Shetland.

Shetland has great appeal for long distances: 10 of the top 20 distances travelled end on the Scottish island.

At the other end of the spectrum, some students only had to travel down the road to take the test; drivers travelled to the Heckmondwike test centre in Kirklees, West Yorkshire, making the shortest journey in the UK, with an average distance travelled of 3.82 miles.

Why are the waiting times at testing centres so long?

In March, three-quarters of drive-thru testing centers had average wait times of more than six weeks.

This is Money reported that at the end of January, 245 testing centres still had waiting times of more than a month, worse than pre-pandemic levels.

Following a Freedom of Information request to the Driving Standards Agency (DVSA), the AA Driving School also found that almost two-fifths of test centres had waiting times of more than five months.

At the time, Camilla Benitz, managing director of AA Driving School, said: “It is unacceptable that we are almost two years into the pandemic restrictions and learner drivers and instructors are still suffering the consequences.”

Continued delays since testing centers had to close their doors in 2020 due to COVID were attributed to a ‘post-pandemic delay’.

Even so By summer 2022, more than half a million people were still waiting for a test, up from the pandemic backlog of cases in 2021, which was just under 500,000.

In early 2023, Parliament was told that pre-pandemic levels should return within a few months and all eligible DVSA staff were asked to resume taking full-time driving tests.

But despite DVSA measures to increase testing capacity, average waiting times got worse or stayed the same at 45 per cent of testing centres.

Between 2 October 2023, when the DVSA began adding more testing slots to try to tackle the backlog, and 29 January 2024, waiting times worsened at 15 per cent of all test centres. They stayed the same at 25 per cent and improved at 60 per cent.

Do exam delays have a negative effect on pass rates?

Between March 2023 and 2024, the UK recorded the lowest number of theory and practical exams taken and passed since 2021

Car background check provider Cap Hpi found a correlation between long wait times for tests and lower pass rates.

According to DVSA statistics, 1,384,678 practical car tests were taken between 2023 and 2024 and 668,038 passed, a pass rate of 48 per cent.

In contrast, between 2021 and 2022, 751,914 practical driving tests were passed, representing a pass rate of 49%.

Between March 2023 and 2024, the UK recorded the lowest number of theory and practical exams taken and passed since 2021.

In 2022, Cardiff driving instructor Jenna Williams told the BBC that waiting times are a reason for failing driving tests: “I think with a backlog of waiting lists for another test, learners feel a lot of pressure, where, as you said, if they fail, they have five to six months and another wait.”

Some links in this article may be affiliate links. If you click on them we may earn a small commission. This helps us fund This Is Money and keep it free to use. We do not write articles to promote products. We do not allow any commercial relationships to affect our editorial independence.