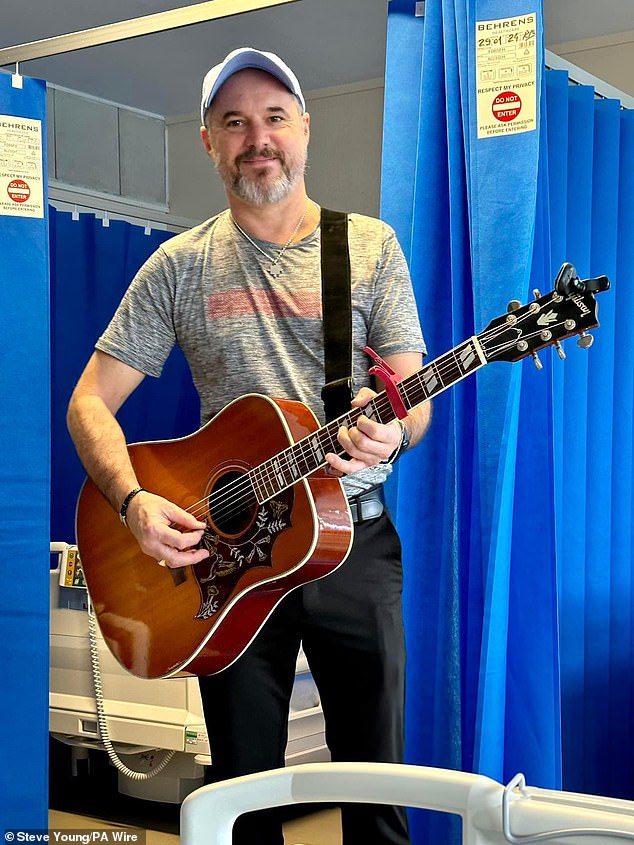

Music teacher Steve Young is among the first patients to receive the world’s first personalized cancer vaccine, with the breakthrough vaccine representing his “best chance” of stopping the disease.

Young, 52, was shocked to learn that an innocent bump on the head was actually melanoma.

Recalling the impact of his diagnosis, Young said he originally thought it was a death sentence as he had had the “bump” in his head for a decade.

“I literally spent two weeks thinking ‘this is it,'” he said.

‘My dad died of emphysema when he was 57 and I really thought, ‘I’m going to die younger than my dad.’

One of the first patients in the trial at UCLH is Steve Young, 52, from Stevenage after a bump on the head he had had for about a decade turned out to be melanoma.

Mr Young was eligible to participate in the trial which has been hailed as a potential “game-changer” for cancer treatment.

The new vaccine is custom designed for people using the specific genetic makeup of their tumor, giving them the best chance of a cure.

It works by telling the body to look for cancer cells and prevent the deadly disease from returning.

Early results from the vaccine, developed by pharmaceutical giants Moderna and MSD, found that it dramatically improved the chances of survival from melanoma, the deadliest form of skin cancer.

Now the University College London Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust (UCLH) is leading the final phase of trials of the therapy, which scientists hope can also be used to stop lung, bladder and kidney cancer.

Young said finding out about the trial at UCLH activated his “geek radar”.

“It really piqued my interest,” he said.

‘As soon as they mentioned this mRNA technology that was being used to potentially fight cancer, I thought “that sounds fascinating” and I still feel the same way. I’m very, very excited.

“This is my best chance to stop cancer in its tracks.”

The new vaccine, which will be tested in about 1,100 patients worldwide, is an individualized neoantigen therapy (INT) and is sometimes called a cancer vaccine.

It is designed to activate the immune system so it can fight the patient’s specific type of cancer and tumor.

Known as mRNA-4157 (V940), it targets tumor neoantigens, which are expressed by tumors and are individual to each patient.

These tumor markers can potentially be recognized by the immune system.

The vaccine encodes up to 34 neoantigens and activates an anti-tumor immune response based on unique mutations in a patient’s cancer.

Dr. Heather Shaw, the trial’s national coordinating investigator, described it as “one of the most interesting things we’ve seen in a long time.”

She said: “I think there is real hope that these are the game-changers in immunotherapy.”

“We’ve been looking for a long time for something that would be added to the immunotherapies we already have, that we know can be life-changing for patients, but with something that has a really acceptable side effect profile.

“And it looks like these therapies may offer that promise.”

To create the injection, a sample of the tumor is removed during the patient’s surgery.

Scientists then sequence the tumor genes to identify proteins produced by the cancer cells, known as neoantigens, that will trigger an immune response.

They are then used to create an individualized mRNA vaccine that tells the patient’s body to generate T cells to combat the tumors’ specific mutational signature.

Mr Young, photographed in January 2023 with melanoma on his head.

The growth, about an inch in diameter, turned out to be cancerous.

Ultimately, Mr. Young had the melanoma removed. Here are the points he had in August of last year.

This eventually healed, leaving him with a scar on the top of his head.

The T cells then attack the tumor, killing the cancer cells, while the immune system should recognize any future rogue cells, hoping to stop the cancer from coming back.

Dr Shaw added: “This is very much an individualized therapy and in some ways it is much smarter than a vaccine.”

“It’s absolutely tailored to the patient; you couldn’t give this to the next patient in line because you wouldn’t expect it to work.”

“They may share some new antigens, but they likely have their own very individual new antigens that are important for their tumor and therefore it is truly personalized.”

Data from a smaller Phase 2 trial published in December found that people with severe, high-risk melanomas who received the vaccine along with MSD’s Keytruda immunotherapy were almost half (49 percent) as likely to die or have their cancer returned after three years than those who were only given Keytruda.

Patients received one milligram of the mRNA vaccine every three weeks for up to nine doses and 200 milligrams of Keytruda every three weeks (for a maximum of 18 doses) for about a year.

The global Phase 3 trial will now include a wider range of patients, including at least 70 UK patients across eight centres, including London, Manchester, Edinburgh and Leeds.

The combination of therapies is also being tested in lung, bladder and kidney cancer.

He received a new anti-cancer injection, which adapts to the patient in just eight weeks and tells the body to make proteins to prevent deadly skin cancer from returning.

Nurse Christian Medina gives patient Steve Young his first injection at University College London Hospital.

The mRNA-based technology in this study is aimed at people who have already had high-risk melanomas removed.

Vassiliki Karantza, associate vice president of MSD Research Laboratories, said, “This trial demonstrates our continued efforts to advance new treatment options for patients with melanoma and we look forward to the expansion of our comprehensive clinical development program to additional tumor types.”

Lawrence Young, Professor of Molecular Oncology at the University of Warwick, who is not involved in the study, said: “This is one of the most exciting advances in modern cancer therapy.

‘Combining a personalized cancer vaccine to stimulate a specific immune response to the patient’s tumor along with the use of an antibody to release the brake on the body’s immune response has already shown great promise in patients whose original skin cancer (melanoma) has been removed.

“The hope is that this approach can be expanded to other cancers such as lung and colon cancer.”