Many families are affected by cancer, but a few seem especially cursed. Mine is one of them. For more than half a century, cancer has stalked my family.

Five members developed the disease and it killed them all, four before the age of 45.

My mother first developed breast cancer when she was 30 and died at age 42 in 1968. My younger sister died at age 24 from abdominal cancer in 1981, and my other sister died from lung cancer six years later, a 32 years old.

My brother’s son, who survived cheek cancer when he was just two years old, would die in early 2019 after developing a bone tumor.

My brother survived lung cancer at age 46, but would have several other cancers before dying at age 69 (just seven months after his son) from pancreatic cancer.

The Ingrassia family siblings (from left: Angela, Gina, Lawrence and Paul. Only Lawrence survived

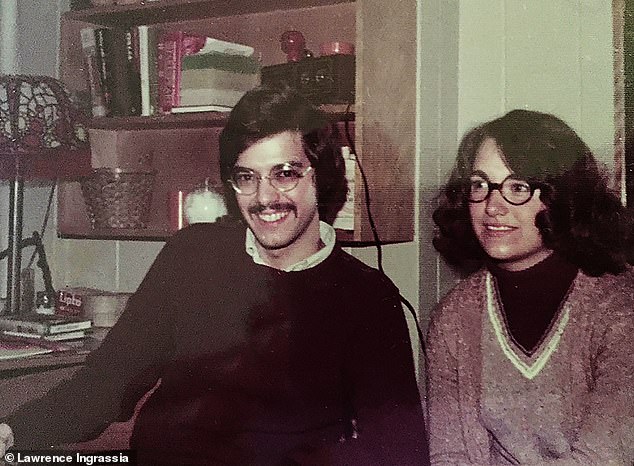

Lawrence’s mother Regina with baby Paul in 1950. Paul succumbed to pancreatic cancer in 2019, after battling lung cancer at age 45 and prostate cancer at age 52.

Each new cancer had brought pain and disbelief. Why was this happening? Couldn’t anything be done? Why was I the only one of the four brothers who was saved? Will I be the next?

For a long time oncologists had no answer.

My nephew Charlie’s ordeal when he was just two years old was especially heartbreaking. What doctors initially believed was a bruise on his cheek was diagnosed as soft tissue cancer, giving him only a 20 percent chance of survival.

Against all odds, Charlie survived, although the radiation prevented the growth of his jaw and deformed his face. She underwent multiple reconstructive surgeries over the next two decades.

During Charlie’s initial treatment, his doctors agreed that the number of cancers in our family was so unusual that they took a piece of skin from our forearms and ran tests to look for anything unusual.

But they couldn’t find anything suspicious. Perhaps because the cancers were different, doctors did not suggest that the cause could be hereditary.

On Gina’s wedding day, with her sister Angela and her father Angelo. Her mother did not live to see this moment.

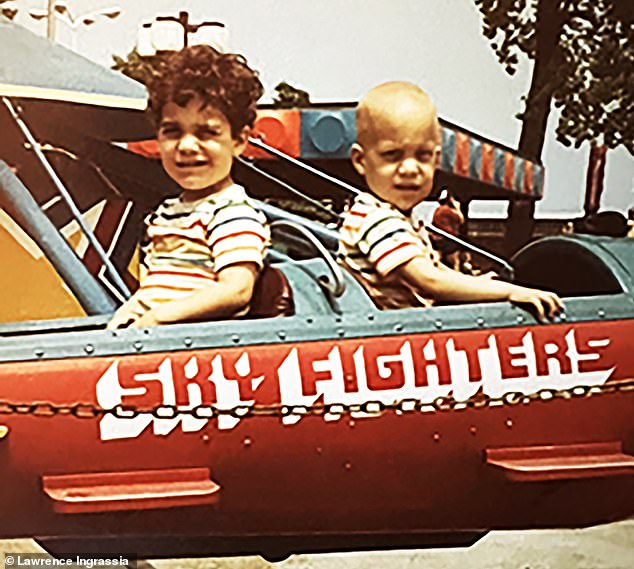

Little Charlie with his brother Dan. Charlie battled and survived soft tissue cancer in his cheek at age two.

The radiation that killed malignant cells in Charlie’s cheek also prevented the growth of his jaw, causing his face to become deformed and requiring multiple reconstructive surgeries.

Maybe the staggering rate of cancers could be related to the fact that our father was a research chemist, we thought. Maybe he brought home small particles of carcinogens on his clothes that were inhaled and years later turned into cancer?

After my second sister died, her husband wrote to a research scientist asking if that might be the case. The answer was that our theory was “unlikely.”

Finally, in 2014, 46 years after our mother died, an oncologist suggested that my brother get genetic testing. This determined that our gene pool was affected by a condition known as Li-Fraumeni syndrome, which occurs when the cancer-fighting gene p53 loses its ability to help prevent abnormal cell growth.

Two pioneering doctors, Frederick Li and Joseph Fraumeni Jr., had spent a couple of decades researching to solve the medical mystery. The syndrome is extremely rare, affecting only 5,000 to 10,000 of 125 million families in the United States.

Lawrence with his sister Angela around 1974. Angela died of abdominal cancer, just months after finding a lump in her abdomen, in 1981.

Gina during treatment for lung cancer in 1987. She died seven months after diagnosis.

Unlike many so-called cancer genes, such as the better-known BRCA gene, which primarily causes breast and ovarian cancer, the p53 mutation can cause a number of cancers to develop within families, often at a very young age. early.

A telltale sign is if a patient has been diagnosed with cancer early in life (sometimes multiple cancers) and has other immediate family members who have suffered a similar fate.

A person with Li-Fraumeni syndrome has a 50 percent chance of developing cancer by age 40 (10 times the normal rate) and a 95 percent chance for life.

There is still no way to stop the relentless cancers caused by the mutation.

However, regular screening of family members with the condition can help detect cancers in their early stages. Studies show that this greatly increases the chances of survival.

Sometimes I wonder if it would have been better if we had known about the mutation in our family sooner. Maybe we would have been more vigilant and some of the cancers would have been diagnosed earlier.

But there’s no way to know if that would have made a difference, since cancer can be so deadly that even early detection doesn’t guarantee survival.

In 2015, a year after learning about Li-Fraumeni syndrome, I decided to get tested myself after many suggestions from my daughter.

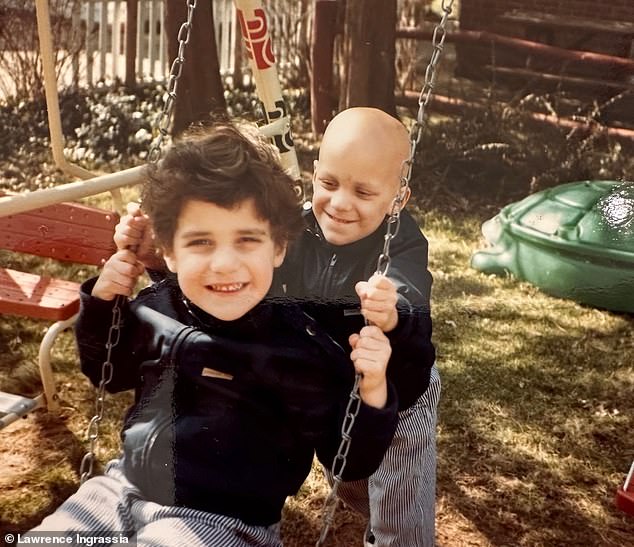

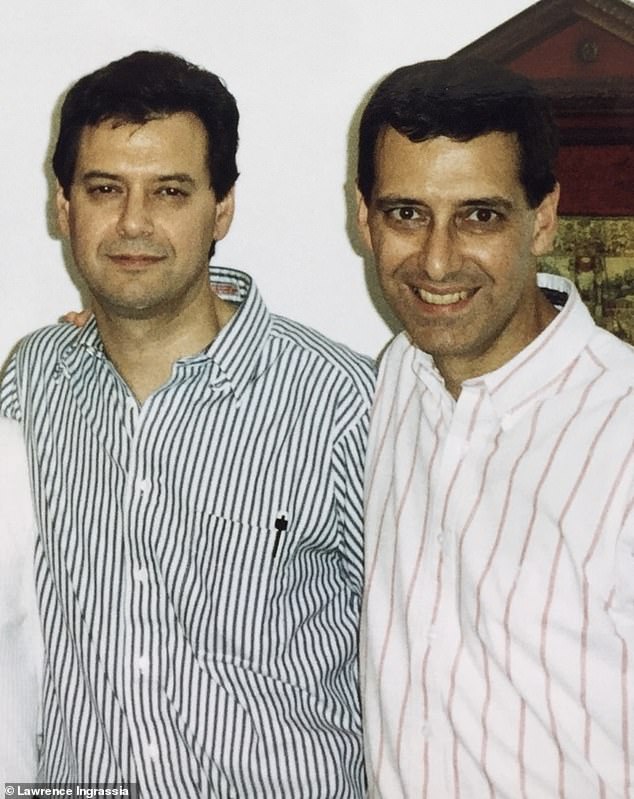

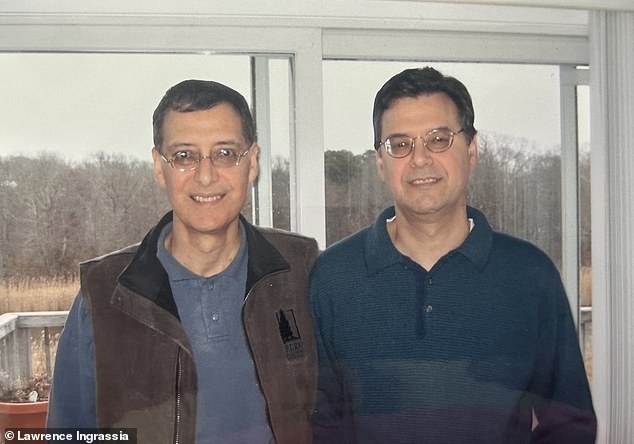

Lawrence’s brother Paul (right) developed lung cancer at age 45 and subsequently had one lung removed and developed other cancers that ultimately killed him.

Paul (left) was later diagnosed with prostate cancer and then pancreatic cancer, which finally killed him in 2019.

Despite the strong family history, I was told there was only a 50 percent chance I had inherited the mutation from my mother’s side. After waiting a month, I got the results: Negative.

Luckily, I was the lucky one who escaped the family curse. I wouldn’t pass it on to my children.

Having lost my family to cancer, a wave of melancholy washes over me from time to time. Every Christmas Eve, I retreat to a quiet place and go through a box of old family photographs.

In a treasured photo, the four of us, as children, are sitting lined up in a row, from oldest to youngest. In another, my younger sister Angela, about five years old, sits in a sleeveless striped cotton dress, smiling despite her missing teeth.

And there’s one of our mother, smiling as she kneels and holds a slightly wobbly baby, Gina. Holding on to memories of the good times means they never really go away.

It may not happen soon, but I believe that one day there will be a cure, with the help of dedicated doctors and Li-Fraumeni Syndrome Association.

And families like mine will be spared the pain of what we have been through.

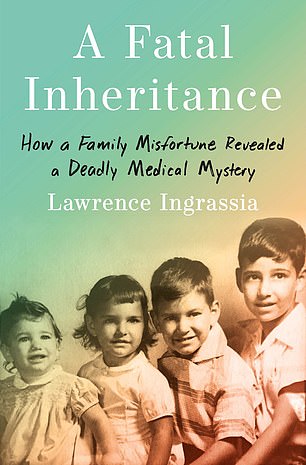

This essay is an adaptation of the book, A fatal inheritance: How a family misfortune revealed a deadly medical mysterypublished by Henry Holt.