Every time I hear that someone’s life support system is about to be disconnected, I feel a wave of fear and horror. What if that person is not beyond help?

You see, I’ve been in that position myself. For almost two months I was in a coma, unresponsive and showing no obvious signs of life.

My mother spent day after day next to my bed talking to me but without getting a response. A month after she was in a coma, a passing nurse told her: ‘I wouldn’t waste your time talking to him, dear. You won’t hear anything.’ Pointing to a monitor next to my bed, the nurse added by way of explanation: “His brain is pretty dead.”

For the next two weeks, doctors prepared my parents for what seemed inevitable: that I would soon be taken off life support.

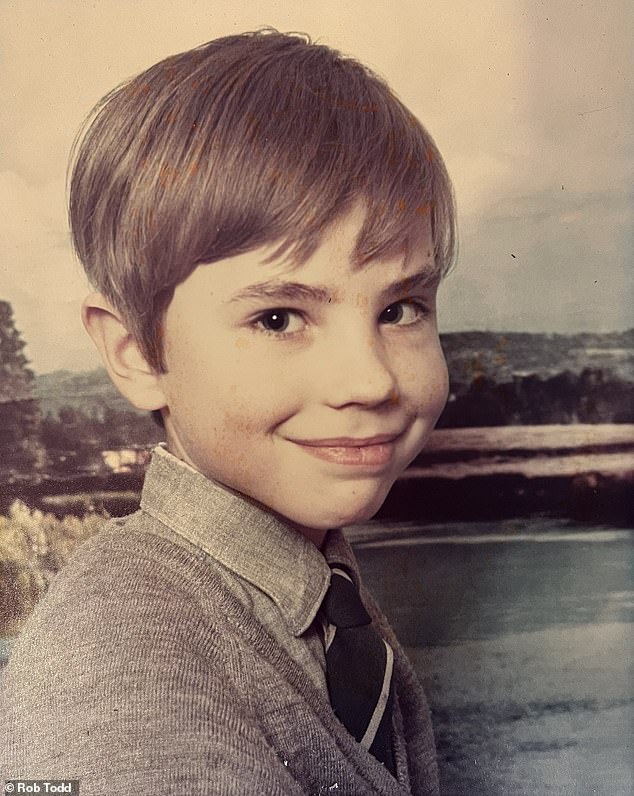

Bill Lumley photographed the day before the accident that left him in a coma in the early 1970s.

At only eight years old, I had fallen into a coma when a van hit me on my way to school.

Late for the school bus, I had run across the main road not far from our house on the outskirts of a village near Cheltenham. The van, which was trying to overtake a car that was out of my field of vision, hit me in the head and, as I later found out, threw me into the air. I landed collapsed on the side of the road, the force of the accident fracturing my leg and leaving me unconscious.

I was rushed to hospital by ambulance and, after a series of scans, my parents were warned that there was a bleed on my brain.

One of the first surgeons who examined me warned my parents that if I came out of a coma, at best I would be in a wheelchair for life.

My parents, however, were determined and visited me daily to see me in intensive care at Frenchay Hospital, near Bristol.

Every day, my mother, Pat, who had been a nurse, brought me news from home. But it was always a one-way conversation: I remained without responding, with my eyes closed. The machines monitoring my brain showed no signs of life. That was until, as the countdown to turn off life support approached, my mother gave her normal report of what had been happening at home and told me that my sister, who was then two, my younger brother (I’m seven) , had been doing my piano practice for me.

At this news I apparently laughed.

They told me that my mother called a nearby nurse. Plans to disconnect my life support system were shelved and over the next fortnight I slowly regained full consciousness.

People always seem incredulous when I tell them that during the coma I believe my brain was active and occasionally alert, but not in a way that would be obvious to anyone who saw me lying there in my incapacitated condition.

My experience of being in a coma was an endless stream of dreams, some of which occurred over and over again. One of those dreams was actually a nightmare. I would see my parents and then have surgery to relieve the pressure on my brain. Then they took me back to another part of the room and my parents weren’t there. I remember desperately trying to tell the nurses that my bed was in the wrong place in the intensive care unit. It was stressful and caused me to panic. I later found out that this really happened. I had several operations and each time they sent me to a different bed.

My experience seems to be more common than you think.

About one in four coma patients who cannot move or speak can still perform complex mental tasks, according to new research published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Researchers from six centers around the world, including Cambridge University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, used brain scans to measure the responses of more than 300 patients who, for example, had been in car accidents or had suffered strokes, when asked to They imagined they were playing. some sport or perform some other motor activity. They found that the resulting brain signals were similar to those of people who responded fully, and in the same parts of the brain.

Dr Judith Allanson, a neurorehabilitation consultant and co-author of the study report, described the finding as “a turning point in terms of the degree of engagement of carers and family members, referrals to specialist rehabilitation and best interest discussions about the continuation of treatment”. life-sustaining treatments.

For decades, assessments to determine a coma patient’s level of consciousness relied on a brain scan and basic tests such as their physical reaction to touch, says Dr. Erika Molteni, a coma sciences expert and researcher at King’s College of Medicine. London.

“As a result, some patients who have shown minimal signs of consciousness, that is, immeasurably low levels, could have been misclassified as being in a vegetative state, which would have led to the assumption that they are not conscious,” says Dr. Molteni. who is also the pediatric leader of the International Brain Injury Association’s disorders of consciousness special interest group.

Even today, understanding of what happens in the brains of coma patients continues to evolve, says Dr. Molteni.

The adoption of more sophisticated brain scans, such as functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), which measures the activity of brain cells by tracking changes in blood flow, means that it has become possible to record levels of consciousness that were previously undetectable. This allows doctors to “differentiate between vegetative and minimally conscious states,” he adds. “And that’s important because it allows for more accurate diagnoses and better-informed treatment decisions.”

Today there is still no clear way to determine what a patient in a coma is experiencing. Some information is known to reach even patients in a vegetative or minimally conscious state, but this varies greatly, according to Dr. Molteni. In 2023, he published research in the journal Neurology that found that some coma patients enter rapid eye movement (REM) sleep cycles, which are considered a sign that conscious experiences or lucid dreams are occurring.

Since waking up from a coma, Bill has enjoyed a 35-year career in journalism and has become a published author. He now lives in London with his American wife and 19-year-old son.

“There are cases in which patients, although they may seem insensitive, may have a certain degree of awareness,” he says.

One concern highlighted in a study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences and based on research by Canadian scientists at University Hospital in London, Ontario, suggests that patients in a coma may feel pain.

During almost two months in a coma I never experienced a moment of pain, even though I was in and out of the operating room; I once had surgery to relieve pressure on my brain and prevent further bleeding after a brain bleed caused paralysis. on my left side during the first month of the coma.

When I left the hospital my body was still contorted, although no longer paralyzed, and I was noticeably uncoordinated. I had to reteach my brain all kinds of things, like writing, walking, and talking. I underwent six months of physical therapy and it took me almost 20 years to be able to walk into a room and not look noticeably uncomfortable.

The weeks I spent in a coma were nothing compared to the time it took me to recover. I was ostracized because it took me years to coordinate my speech with my thoughts. I could completely understand what others were saying: the problem was meaningful, coordinated responses. I didn’t make any friends at school, none, that is, until I went to an all-girls school for my A-levels exams, along with two other boys.

It took me until my mid-20s to rebuild enough of my left-right coordination to not look unusual. But at least I had the opportunity to do it, largely thanks to my parents.

I went to university, enjoyed a 35-year journalism career, am a published author and live in London with my American wife and 19-year-old son – not bad for a kid whose brain was supposedly dead.