It took months of exams, scans and blood tests for a Virginia mother to finally receive life-changing health news for her daughter Eden.

As she entered the third trimester of her pregnancy, Cheyenne suspected something was wrong with her unborn baby while she was losing weight. Shortly after, doctors would discover that Eden was not growing at a normal rate.

When she was born, Eden was small, but generally healthy. However, when she failed to meet several important milestones, such as holding her head up or sitting up on her own, Cheyenne’s concerns resurfaced and she pressed her doctors for answers.

Finally, they performed complete sequencing of Eden’s genes, which revealed that the girl had 16p11.2 deletion syndrome, a rare genetic disorder that affects approximately one in 5,000 people.

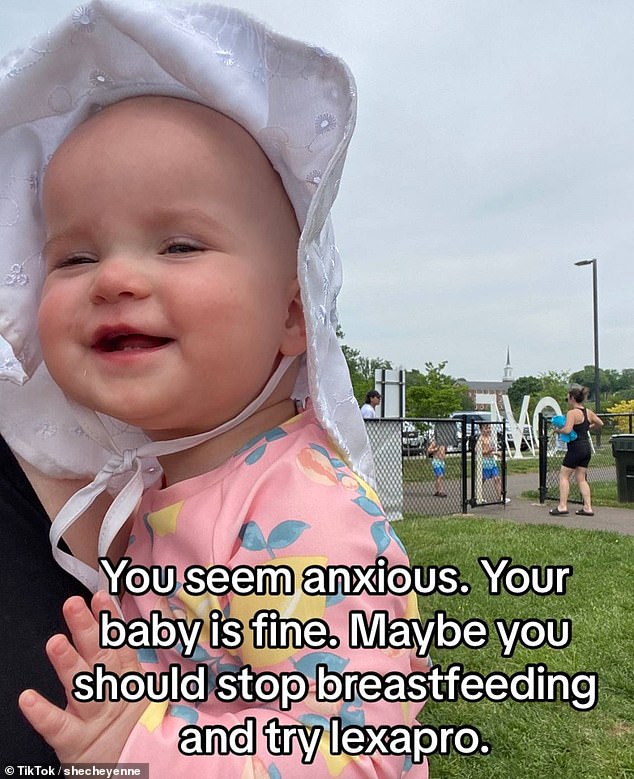

Cheyenne (pictured holding her baby Eden) had a difficult third trimester when she discovered her baby was not growing at a normal rate.

Eden was born happy and healthy, but when she was still having trouble holding her head up at four months, Cheyenne suspected something was wrong.

At 32 weeks pregnant with her second child, Cheyenne went to her doctor for a checkup. Your baby’s fundal height was smaller than normal.

Fundal height is a measurement during pregnancy to approximate the size of the uterus and evaluate fetal growth. It is measured from the top of the mother’s uterus (the fundus) to the pubic bone in centimeters and usually corresponds to the number of weeks of pregnancy.

At 35 weeks, Cheyenne was able to have a growth scan, which revealed that her baby was only 28 weeks old.

Cheyenne learned that her baby had intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR), a potentially dangerous complication that could mean low birth weight, developmental delays, an increased risk of respiratory distress syndrome and feeding problems.

IUGR affects about 10 percent of babies and is defined as weighing less than nine in 10 babies (below the 10th percentile) of the same age.

The delay was most marked in Eden’s abdomen, so Cheyenne received steroid injections in her arms to speed up the growth of her baby’s lungs, followed by non-stress testing (NST), which evaluates the health of the fetus by monitoring the changes in heart rate as you progress. she moves in the womb.

Cheyenne said that at 35 weeks pregnant Eden “looked good on the NST.”

She had two NSTs a week for the next three weeks until she gave birth in April 2023. Eden was small, weighing five pounds, seven ounces, but not so small as to worry the doctors and nurses.

The average American-born girl weighs seven pounds, two ounces, but Cheyenne never expected her baby to be so big. Their first daughter weighed six pounds, 15 ounces.

Eden was generally healthy, but in the months that followed, Cheyenne realized that her baby was missing important milestones, including the ability to turn her head from side to side and hold her head on her own, something babies begin to do. to do between two and two. four months.

Eden also had difficulty pushing her legs down, another milestone typically seen around two months.

Cheyenne said People: ‘The weeks before giving birth were full of anxiety for me. I knew deep down that something wasn’t normal and no one could tell me what it was.

“After a few months, I realized that I was still very limp and had no control of my head.”

Still, friends, family and even medical professionals assured him that everything was normal. Eden’s delays could be explained. Each child develops at their own pace, so their delay could simply be part of their unique timeline.

Cheyenne said: ‘This was the beginning of our journey. At that moment I knew, in my maternal instinct, that my IUGR was related.’

Eden underwent an EEG to make sure she wasn’t experiencing seizures. He also underwent x-rays because his hips were not supporting his weight.

At Eden’s 4-month checkup, she was referred to physical therapy to help build her strength and muscle tone. He had been diagnosed with hypotonia or muscle weakness.

Cheyenne said: ‘We did a CT scan of Eden’s head due to her macrocephaly (larger head) and an EEG for suspected seizures. They both came back clean. We also did a hip x-ray because he couldn’t put weight on his legs. That was clean too.’

The diagnosis of hypotonia was helpful. She connected Cheyenne with trained physical therapists who could help Eden achieve first-year milestones, from holding her own head to sliding.

But Cheyenne’s maternal instinct persisted.

She said: ‘People were telling me I needed to relax and that Eden was fine. They told me well-meaning stories of their retarded children and told me to stop comparing Eden to my oldest daughter. I knew there was something more.’

In early 2024, Eden’s motor skills (lifting her head, pushing her arms, and rolling over) were showing signs of regression, so Cheyenne took her concerns to a new pediatrician and neurologist.

According to the Alberta Infant Motor Scale, which assesses gross motor skills in infants, ‘Eden was not (and still is not) on the chart after previously being in the 10th percentile.

“So if you lined Eden up with 100 other babies her age, she wouldn’t even be close to any of them,” Cheyenne said.

A subsequent MRI was normal, but a full panel of genetic testing picked up something that a year’s worth of scans didn’t.

The photo shows Eden preparing to undergo a CT scan, one of many performed over about a year.

Cheyenne learned in July that Eden has 16p11.2 deletion syndrome, a genetic disorder caused by the deletion of a small segment of chromosome 16 at a specific DNA location known as 16p11.2.

That missing piece affects genes that are essential for brain development and function.

As a result, children born with 16p11.2 deletion syndrome often have more difficulty learning to walk, talk, and socialize with other children.

In 16p11.2 deletion syndrome, people often have more problems with expressive language skills (using words and speaking) than with receptive language skills, which involve understanding what others say.

Some people born with this condition may also experience repeated seizures, although Cheyenne said Eden has not shown any signs of this.

About one in 5,000 people have the chromosomal abnormality and about 24 percent of them experience seizures. Researchers have found no evidence to show that it shortens a person’s life expectancy.

Cheyenne shared the details of her difficult third trimester on TikTok, where she has since found a community of mothers who have had to advocate for themselves and their children.

Friends and family told Cheyenne to stop worrying about Eden (pictured), who was generally healthy and happy.

The results were a relief to Cheyenne, who said she learned about them in the parking lot of a facility where she had just given Eden an evaluation for a program called Early Intervention, a system of services like physical and speech therapy aimed at helping the babies. and young children with developmental delays.

She said: ‘(I) found that Eden, at 15 months, was still only at a 6-month level in all developmental domains. I considered running back and saying, “Wait! This is the reason!”

While she was relieved to receive the diagnosis, Cheyenne was frustrated that it took more than a year.

She said: “I had no idea how hard I would have to fight and defend my daughter and now I realize I’m not the only one who has to do it.”

Cheyenne shared her story on tiktokwhere she found community with other mothers struggling to get answers for their struggling children.

She told People: “There is an entire community of mothers who suffer in what feels like silence because providers and others around us don’t believe what we say when we express concerns about our children.”

She hopes her story inspires parents to speak up if they suspect there is something unusual about their baby’s development.

Cheyenne said, “At the time, I was worried I was being too “extra” or annoying.

‘It’s okay to get a second and third opinion, and if a provider thinks you’re being annoying, then they’re not the right choice for your family anyway.

‘If you care about being a good mother, you probably already are. I spent months worrying about whether this was my fault or not. Did I take too much nausea medication? Is it because I hug her too much? Turns out this had nothing to do with me.