Understanding that she had advanced bowel cancer at the age of 36 was understandably a devastating shock to Carla Mitchell, not least because the disease is normally associated with people aged 60 and over.

What Kent’s marketing representative didn’t know at the time was that she was born with Lynch syndrome, a little-recognized genetic disease that affects up to 200,000 Britons and significantly increases the risk of numerous cancers in the early stages of life. life.

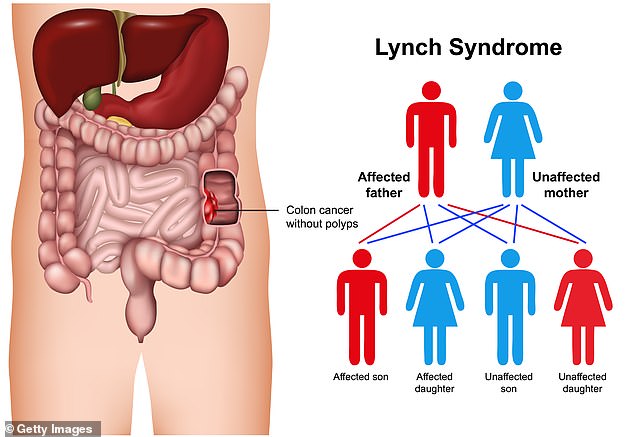

People with Lynch syndrome have mutations in one of four genes (MLH1, MSH2, MSH6 and PMS2) that normally help repair DNA errors in cells. Instead, mutations mean the cells are more likely to develop into cancer.

As a result, they have a more than 70 per cent higher risk of cancers affecting the bowel, uterus, ovaries, stomach, gallbladder, prostate and urinary tract, according to Cancer Research UK.

Lynch can be hereditary, so first-degree relatives (parents, siblings, children) of someone with Lynch have a 50 percent risk of having the genes. However, if the condition is identified early in life (through genetic testing), carriers can be given counseling to help reduce their risk.

For example, taking a low-dose aspirin daily could reduce the risk of bowel cancer by 40 percent by reducing the inflammation that causes healthy intestinal cells to become cancerous.

However, NHS figures show that 95 per cent of Lynch carriers are unaware of their genetic risk of cancer, and only 5 per cent have been identified.

This is despite the fact that Lynch’s genetic screening tools are available in the UK and that it is official NHS policy to screen all bowel cancer patients for this condition (however, recent studies show that this has been done only partially).

There is now more impetus to find people with the syndrome, after the NHS launched a national bowel screening program earlier this year.

Carla’s crushing diagnosis came out of nowhere in 2021.

‘Looking back, there were red flags: I was unusually tired, but it was the end of lockdown, so I put it down to my reduced physical activity and hectic work schedule.

‘But it wasn’t a kind of tiredness I had experienced before: I felt heavy and my legs hurt. If I tried to run up the stairs, my heart would race.

A blood test by his GP revealed that his iron levels were low; They told her she was “dangerously anemic and should go to the hospital.”

“I panicked. I had never been to the hospital before,’ he said. He was given iron infusions and further tests were performed.

Carla Mitchell was diagnosed with bowel cancer at age 36 in 2021

Days later, on Christmas Eve 2020, her GP called her to tell her that they had found blood in her stool and that she urgently needed a colonoscopy (an examination of the intestine with a camera).

Within weeks, Carla was diagnosed with stage 3 bowel cancer that had spread to her lymph nodes. He underwent surgery to remove the tumor, followed by three months of chemotherapy. When his treatment ended in August 2021, a scan found no evidence of cancer.

Only then did someone mention the possibility of genetic testing for Lynch syndrome.

“Six months later I received a letter from the genetics team at Guy’s Hospital informing me that I had a form of Lynch (a mutation in the PMS2 gene),” Carla recalls.

‘I didn’t take the news well; It was harder than receiving my cancer diagnosis. Lynch means there’s always a cloud over my head.

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence recommended in 2017 that all people diagnosed with bowel cancer be tested for the syndrome.

But a February report from NHS England’s National Disease Registry Service, published in the European Journal of Human Genetics, warned that these guidelines were not being implemented and, as a result, doctors were failing to detect up to 700 people a year with Lynch.

Experts believe that women with endometrial (or uterine) cancer, another gene-related disease, should also be screened.

“For many women with Lynch, endometrial cancer is the first cancer they develop,” Clare Turnbull, professor of cancer translational genetics at the Institute of Cancer Research in London, told the Mail.

But a study she co-authored, published in October in the BMJ Journal of Medical Genetics, found that only one in eight patients with Lynch syndrome was diagnosed through endometrial cancer screening in England in 2019.

Lynch syndrome significantly increases the risk of numerous cancers early in life

Professor Turnbull argues that if Lynch’s patients are informed of their genetic danger, they could benefit from strategies to significantly reduce their risk of fatal cancers.

Some experts advise women with Lynch to have their ovaries, fallopian tubes, and uterus removed once they have finished having children, to protect against endometrial cancer, for example.

Professor Turnbull says greater efforts are also needed to locate relatives of those affected, as they may have the disease but not know it.

Meanwhile, NICE recommends that people with Lynch also have a colonoscopy every two years to check for any signs of bowel cancer.

But this is fraught with difficulties, says Professor Turnbull.

“Many of these cancers are not easy to detect; they do not stand out from the colon tissue as polyps, for example, as normal bowel cancers do; many of them are flat and hidden,” he says.

But Naser Turabi, head of evidence and implementation at Cancer Research UK, insists screening is “extremely effective” at detecting early-stage cancer.

However, he admits that colonoscopies for Lynch sufferers need to be more thorough than usual, as doctors are “looking for something that often doesn’t cause symptoms.”

In February, NHS England announced a world first: routine bowel cancer screening every two years for those already suffering from Lynch syndrome, identified either through family members or because they have already had cancer .

The problem is that this covers only the 10,000 people in England who are already on the NHS Lynch syndrome register, not the approximately 190,000 who have not yet been diagnosed.

But NHS England says this coverage will improve as genetic testing becomes more widespread. For example, he says, 94 percent of people diagnosed with bowel or endometrial cancer between 2021 and last year were screened for Lynch syndrome, up from just 47 percent in 2019.

But questions remain about how effectively the biennial assessment is implemented, Turabi says.

“There is a lot of pressure on genomic services,” he says. “And Lynch’s tests are not as urgent as, say, genetic testing for lung cancer, where they would help doctors determine what specific treatment a patient should receive for their particular form of the disease.”

Meanwhile, the need to identify more people with Lynch becomes increasingly vital as scientists at Oxford University are working on a vaccine that could prevent them from getting cancer.

One of the researchers, Dr. David Church, a clinical scientist and oncology doctor, said the vaccine will help patients’ immune systems detect cells that become cancerous due to DNA flaws in Lynch syndrome.

“As the cells proliferate, they deactivate the protein mechanisms by which the immune system recognizes them, effectively hiding themselves.”

The hope is that a jab will “rev up” patients’ immune defenses so they can kill rogue cells before they go covert.

Another line of attack is through the English National Lynch Syndrome Registry, a new database of Lynch patients that will compare patients’ DNA data with their cancer diagnosis, treatment and outcomes, in the hope that this Help doctors develop the most effective solutions. treatment and prevention strategies.

Meanwhile, Carla’s mother is going through the genetic testing process; As Carla, who does not know her father, explains: “we don’t know of any cancer in the family, although you can have the mutation and never develop cancer.”

She and her husband Simon would like to have children and are weighing up their options, especially as she has been advised to have a hysterectomy at age 45 to prevent endometrial cancer.

“If we have a child naturally, then they have a 50/50 chance of having Lynch,” he says.

«With IVF we could examine the embryos to eliminate those with the Lynch mutation. But IVF can take years.’

But Carla remains resolutely positive.

“I’m sure there is a future for people with Lynch,” she says.

“Even if my son had it, I am confident that modern medicine will ensure he has a healthy future.”