A bricklayer who developed an incurable lung disease after making quartz kitchen worktops has shared the devastating impact it had on his life.

Malik Al-Khalil, 31, was first hired to make the modern counters six years ago and remembers coming home covered in dust created when the material was cut.

What he didn’t know was that the dust, which he also inhaled, was slowly destroying his lungs: today he has difficulty breathing and cannot walk without help.

His body has been ravaged by silicosis, a terrifying disease that doctors say could kill him.

Mr Al-Khalil, originally from Syria, is one of the few public faces of the scandal that has already killed one British stoneworker and left nearly a dozen people seriously ill with silicosis.

A bricklayer who developed an incurable lung disease as a result of working with quartz kitchen worktops has shared the devastating impact it has had on his life (file image)

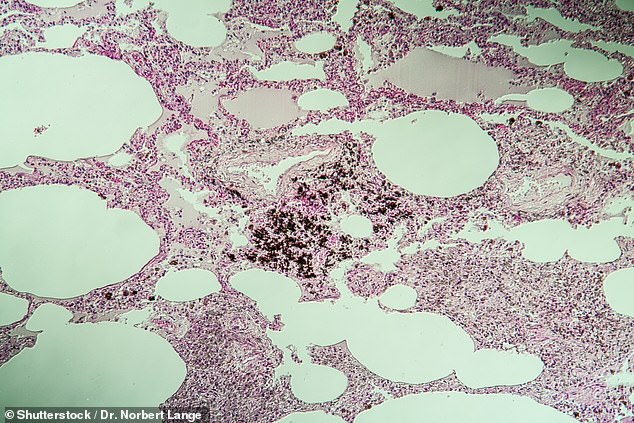

Silicosis, through fine particles inhaled by workers, causes internal scarring and inflammation of the lungs. Image of silicosis of lung tissue under magnification

However, doctors have warned that the known cases are likely just the tip of the iceberg.

Such is the concern that this week doctors called on the Government to ban quartz countertops, to protect contractors and builders.

The most popular quartz countertops are made of 90 percent ground quartz and 10 percent resins and pigments.

When processed into their final countertop form, this results in the release of potentially harmful fine silica dust particles into the air.

Cheaper than granite or marble, countertops have become a staple in kitchen renovations, but it’s workers like Mr. Al-Khalil who are paying the price.

“This silicosis, once it starts in your body, it doesn’t stop,” he said. Yo.

‘I want everyone working on this project to know what’s going on with this material.’

Mr. Al-Khalil says No precautionary measures, such as “wetting” the stone to remove dust, were taken when working with quartz.

He and his colleagues were not provided with any specialized equipment to prevent inhalation beyond standard masks, he added.

She developed a bad cough last August and sought help from doctors at the hospital, but was told it was probably a flu-like illness.

But her condition worsened and she began experiencing vomiting, joint pain and difficulty breathing.

When she sought help again, she said doctors suspected she had a bacterial infection called tuberculosis.

However, Mr Al-Khalil’s condition continued to rapidly worsen and he became unable to eat or drink and his weight plummeted.

It was then, in September last year, that tests revealed he had silicosis and doctors warned him the disease could kill him.

He was out of hospital until April this year after needing surgery after his lungs collapsed, after which he needed more intensive care.

After his diagnosis, Mr Al-Khalil discovered that two colleagues had also been diagnosed with silicosis.

“I now know nine people who have the same silicosis: they all work in factories, they all work as bricklayers, they all have the same job.”

Silicosis, through fine particles inhaled by workers, causes internal scarring and inflammation of the lungs.

This increases the risk of lung infection, reduces their overall effectiveness, and can cause life-threatening organ failure.

Shortness of breath can also put a life-threatening strain on the heart.

Silicosis is not a new disease; it has already ruined the lives of miners, builders and bricklayers in the UK in the past.

Britain’s health and safety watchdog, the Health and Safety Executive (HSE), estimates that 12 people die each year as a result of exposure to silicosis.

However, the HSE says this is likely to be an underestimate.

Expensive quartz countertops are made from one of the hardest minerals on Earth, which when processed, releases potentially harmful fine dust particles.

Last year there were 11 cases in the UK, including one death from the progressive disease, caused by inhaling crystalline silica dust.

British doctors said that last year, eight men aged between 27 and 56 were diagnosed with silicosis after visiting a clinic specialising in occupational lung diseases.

Two of them were being evaluated for lung transplants, three for an autoimmune disease and two for an opportunistic lung infection caused by nontuberculous mycobacteria when the disease was discovered.

Exposure to the dust that triggered the disease had a median duration of 12.5 years, but ranged from four to 40 years, and all the men had worked for small companies with fewer than ten employees.

Of the cases, six were born outside the UK and seven were or used to smoke, according to doctors writing in the BMJ journal Thorax.

Doctors treating them said more needed to be done to regulate exposure to the dust and urged officials to consider a total ban.

Dr Joanna Feary, Respiratory Consultant at Royal Brompton, is currently treating patients with stone-induced silicosis.

They wrote: ‘The occurrence of illness is likely to be related to exposure levels, suggesting that levels, at least for some of the UK cases… were extremely high and imply that employers failed to control dust exposure or comply with health and safety regulations.

‘The market is dominated by small companies where regulation has proven difficult to implement. In addition, at least some countertop manufacturers may not provide adequate technical information related to potential risks.

“Even after cessation of exposure, disease progression has been observed in more than 50 percent of cases over (an average of) four years. Therefore, disease prevention is critical.”

The problem is not just a British problem. Earlier this year, Australia became the first country to ban the type of worktops that have been linked to a new wave of silicosis, following a spate of 579 cases among bricklayers in the country.

Lung disease expert Dr Johanna Feary said there is “no good treatment” for the deadly disease.

“The diagnosis can be devastating. It affects young men, many of whom have only been working with this material for a few years,” he told The Sun.

In a statement, a spokesman for the Government’s Department of Health and Safety said: ‘Our sympathies are with those who have lost loved ones to any work-related illness.

‘Great Britain has a robust and well-established regulatory framework to protect workers from the health risks associated with exposure to hazardous substances.

‘We continue to work with industry to raise awareness about managing the risks of exposure to respirable crystalline silica and are considering options for future interventions to ensure workers are protected.’

A HSE spokesman said: ‘Our condolences are with those who have lost loved ones to any work-related illness.

‘Great Britain has a robust and well-established regulatory framework to protect workers from the health risks associated with exposure to hazardous substances.

‘We continue to work with industry to raise awareness about managing the risks of exposure to respirable crystalline silica and are considering options for future interventions to ensure workers are protected.’

As for Mr Al-Khalil, he still hopes to recover and says he wants to move to a coastal town and continue taking driving lessons.