Not many people can say they have lived with cancer for almost 43 years. Katie Thorington, 45, from Peterborough, is one of them.

When he was just two years old he was diagnosed with leukaemia, the most common blood cancer in children, with around 650 new cases in children and young adults in the UK each year.

Six years later, when she was eight, she went into remission, but at 13 she learned that powerful drugs and radiation therapy had damaged her brain and caused epilepsy.

Worse still, less than two decades after being declared cancer-free, she developed another form of the disease linked to childhood cancer treatment — this time, an extremely rare type of tumor that develops in the jaw.

Now in his mid-40s, doctors have discovered tumors in his brain.

The project is supported by former childhood cancer patients such as Katie Thorington, who, in a tragic twist, developed a secondary cancer from the same treatments used to stop her childhood leukaemia. Katie is pictured here with her father.

But there may be hope on the horizon for thousands of patients like her, who face long-term consequences of childhood cancer treatment.

Cancer Research UK, the country’s largest cancer charity, has unveiled a new £28 million research initiative that will help develop new, targeted therapies gentle enough for children.

Currently, there are few specific medications and treatments designed for children with cancer.

Most pediatric cancer patients are given modified doses of drugs designed for adults, which can have a range of negative side effects, from developmental problems to infertility.

As in Ms Thorington’s case, this may include the risk of developing further cancers in the future.

Ms Thorington, from Peterborough, said despite the challenges of being a childhood cancer patient, she still had a happy upbringing and paid tribute to her parents.

The initiative, called C-MoreIt is designed to address what the charities behind the project call the “market failure” in the development of new cancer drugs for children.

They noted that between 2007 and 2022 only two such drugs were developed, compared to 14 for adults.

The initiative, in partnership with medical research charity LifeArc, will involve funding efforts to develop new drugs, help researchers gain access to state-of-the-art facilities and accelerate the delivery of novel medicines to patients.

Ms Thorington, from Peterborough, said that despite the challenges of being a childhood cancer patient, she had a happy upbringing and paid tribute to her parents.

“At that time there was not much hope or support for parents. However, I only have happy memories from that time,” she said.

“My parents were protective, but their unwavering love, care and commitment to overcoming difficulties helped normalize the situation.”

Ms Thorington, who has served on the C-Further “patient engagement” panel, said she hoped the research programme would bear fruit for children with cancer today.

While her cancer treatment, a combination of radiotherapy and chemotherapy, was successful, it was not without consequences.

‘The second cancer was a head and neck cancer, a rare form of squamous odontogenic tumor (jaw cancer), and I was unable to have further radiotherapy or chemotherapy, but I did undergo extensive surgery and extensive facial reconstruction.’

Exposure to radiation and potentially toxins from the chemotherapy used in her treatment is thought to have caused changes in her cells that led to the development of this cancer, medically known as a “second cancer.”

Even today he still faces cancer fears, with some tumors having recently appeared in his brain.

While they thankfully turned out to be benign, Ms Thorington said the consequences of her cancer treatment as a child had affected her deeply.

“I am fortunate to have the support of my family and friends, but still, I feel that the emotional impact of the events I have inherited has robbed me of some opportunities and my self-confidence has also suffered,” she said.

‘I feel motivated to help make a difference.

“I want to raise awareness and help improve treatments.”

Ms Thorington, who has served on the C-Further “patient engagement” panel, said she hoped the research programme would bear fruit for children with cancer today.

“The new, modern and collaborative approach of the C-Further Consortium gives me hope for positive results in terms of survival and long-term side effects,” he said.

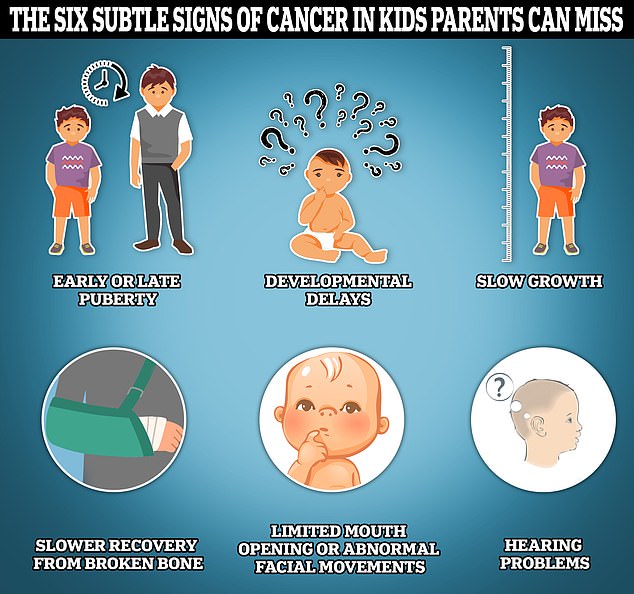

This graphic highlights some of the lesser-known signs of cancer in children, including early or late puberty, developmental delays, slow growth, slow recovery from bone injuries, limited or abnormal facial movement, and hearing problems.

We need more specific treatments, with less toxicity and that are less invasive.

Less emphasis on basing treatment plans for children and young people on the successes of those designed for adult physiology.

Dr Iain Foulkes, CRUK’s director of research and innovation, said that while designing cancer drugs for children was challenging, it was no excuse for decades of slow progress.

“There is a market failure in pediatric oncology,” he said.

‘C-Further is not just another initiative. It is a ray of hope for families facing the devastating diagnosis of childhood cancer.

‘Our aim is to ensure that children and young people receive medication specifically designed for their specific needs, reducing the long-term side effects suffered by many young survivors.’

Dr David Jenkinson, director of childhood cancer at LifeArc, added: “While survival rates for children with cancer have improved in recent decades, children often suffer life-changing side effects from treatment.”

‘Most current treatments for childhood cancers were developed for adults and there is an urgent need for safer and more effective solutions for children.

‘C-Further is an opportunity to address the challenges that hinder the commercialization of new personalized medicines and to drive life-changing innovations that provide children and young people affected by cancer with the best quality of life.’

Childhood cancer, defined as cancer affecting children under the age of 14, remains rare in the UK, with nearly 2,000 cases diagnosed each year.

This represents less than one per cent of all cancers diagnosed in Britain each year and equates to one in every 420 boys and one in every 490 girls contracting some form of the disease.

Most childhood cancers are diagnosed between birth and five years of age, with leukemias and brain cancers being the most common types of cancer diagnosed among children.

Although the vast majority of childhood cancer patients survive into their teens and 20s, about 250 die each year from the disease.

Although childhood cancer survival rates have more than doubled since the 1970s, cancer remains the leading cause of disease-related death in children in both the UK and the US.