A white woman in Canada has revealed how an IVF mistake in the 1990s left her feeling like an outsider in her biracial family.

Hadeya Okeafor’s mother is white and her father is black. For much of her life, she was told she was “pink like mommy” and her siblings were “dark like daddy.”

She didn’t question the difference growing up, and felt as loved by her family as any sibling, even when visiting her cousins in Ghana.

She saying:’You know, it’s like with dogs, you can have a white dog and a black dog in the same litter.

‘At around 11 or 12 they finally told me.’

Instead of using her father’s sperm to fertilize an egg, doctors used the sperm of an unknown white and dark-skinned woman.

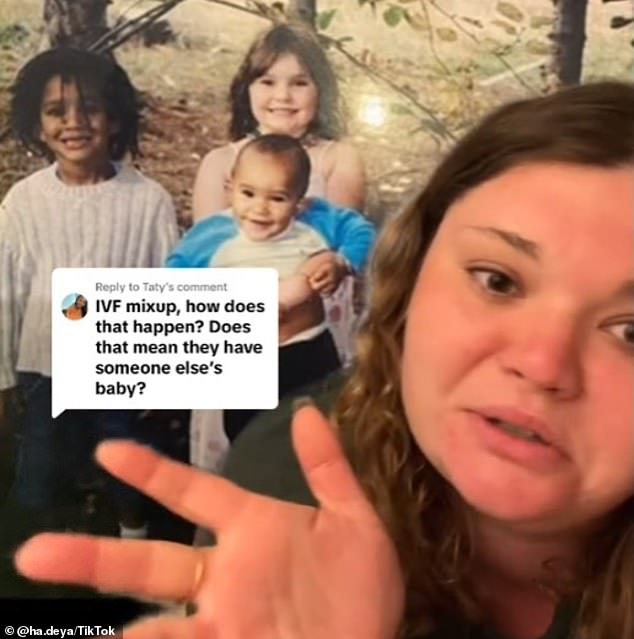

Ms Okeafor visited Ghana with her family to visit her cousins. She is pictured here with one of her cousins.

In a new TikTok, Hadeya Okeafor detailed the IVF mistake that resulted in her Black father’s sperm not being used to fertilize her white mother’s egg, leaving her looking very different from her siblings.

When her parents confronted the clinic in Toronto In what they believed was the latest in a series of similar mistakes, they were told it would take up to a year for Hadeya’s skin to darken.

When it became clear that Dr. Khamsi had made a mistake, Ms. Okeafor’s mother sued the practice and won.

The in vitro fertilization process involves the use of eggs and sperm from a couple or donors.

It is a process in which eggs extracted from a woman’s ovaries are fertilized outside the uterus using sperm samples and implanted in the woman’s uterus.

Doctors perform about 4,000 IVF cycles each year in the U.S. and more than 2 million worldwide.

While it is difficult to determine an exact number, these mix-ups are believed to be rare, although exact figures are difficult to pinpoint and could be higher than previously thought.

Errors and accidents often go unreported in the industry, which is largely… self-monitored.

In one of the few studies of IVF errors, researchers found that Boston IVF, a large chain of fertility clinics, reported errors in 0.23 percentor about one in every 400 cases.

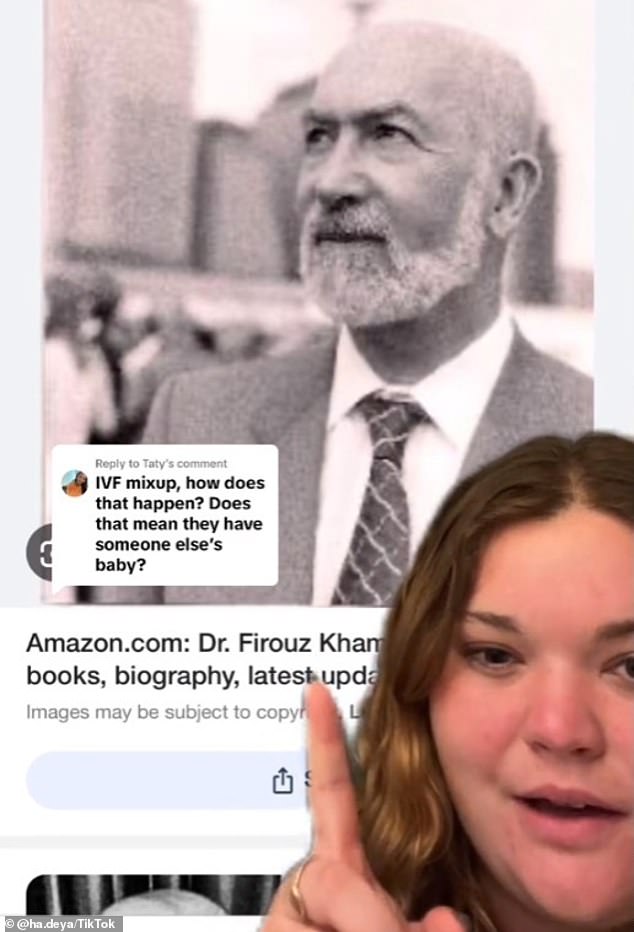

Dr. Firouz Khamsi of the Toronto Fertility Institute fertilized the egg with sperm from a white and dark-skinned man.

Ms. Okeafor is pictured with her siblings. She said the turmoil has never affected her relationship with them, which remains strong to this day.

He appears in the photo again with some of his siblings. He found out about the mix-up when he was around 12, but said he didn’t care and decided to love his family and his place in it just the way they are.

In Ms. Okeafor’s case, the male donor was a tall, brown-haired white man.

“When my parents met with Dr. Khamsi to talk about this, he simply told them, ‘You should be grateful for what you have, you have a beautiful family, you got what you wanted. Take me to court if you want, but that’s what insurance is for.'”

Dr. Firouz Khamsi was the owner of the Toronto Fertility Institute, which he promoted as Canada’s first independent fertility clinic since 1984.

In the past, he had had problems with the staff. Although a disciplinary board eventually found that he met standards of care, a patient of his was dissatisfied with his bedside manner and his failure to explain that IVF was not always successful. In fact, at the time, the chance of success was less than 10 percent.

She complained about him in 1994, and an independent specialist concluded that Dr. Khamsi’s care had been deficient in the initial history and physical examination, the tests on which he based his diagnosis, his records of conversations with the patient, and his emotional support of the patient.

Okeafor hasn’t let the IVF mistake dictate her life or her relationship with her family, which is and always has been strong. She showed off photos of her siblings and father in a new TikTok video, including shots of them all together and close-knit.