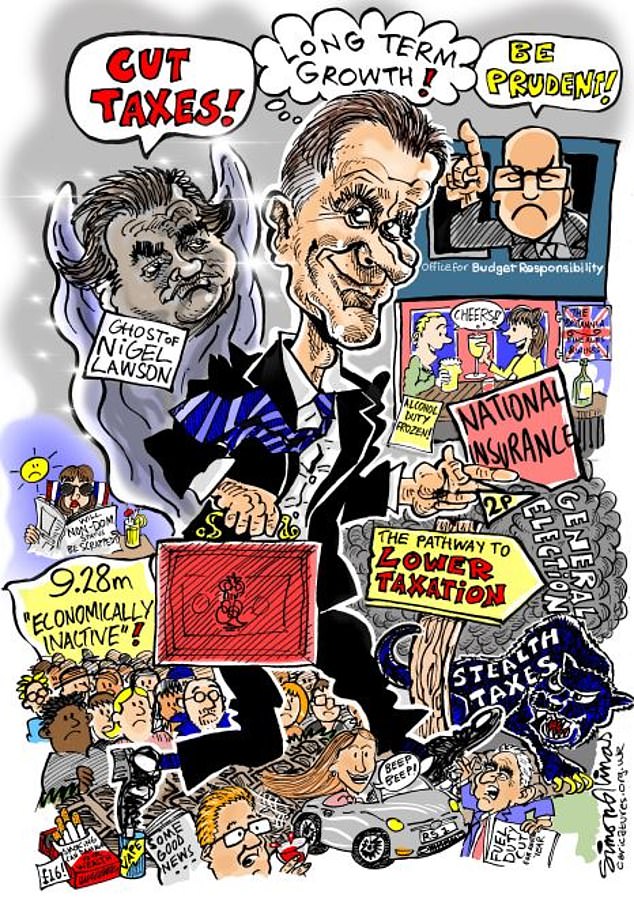

There are two things that can be said with certainty about the Budget. Firstly, the forecasts underlying Chancellor Jeremy Hunt’s tax and spending plans will be wrong.

Those of the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR), which sets and increasingly sets the Government’s duties, tend to be.

Secondly, fiscal rules designed to reassure financial markets that Britain can still pay its way in the world will continue to be manipulated.

This is because chancellors of any political stripe cannot resist bending them.

The key rule – the fall in national debt as a proportion of economic output at the end of the five-year forecast period – was met only by very small margins.

The forecasts underlying Chancellor Jeremy Hunt’s tax and spending plans will be wrong. Those from the Office of Budget Responsibility are usually

This was because Hunt spent what little leeway he had on £13.8bn in pre-election donations in a nod to one of his tax-cutting predecessors, Nigel Lawson.

The achievement of this objective was based on some heroic assumptions.

As the OBR mischievously noted: “The fiscal forecast is…conditional on tax receipts rising to near-record levels, including through planned increases in fuel taxes that have not, in practice, been implemented since 2011″.

It also assumes that there will be no real growth in public spending per person over the next five years, even though some major public services – particularly the NHS – will see their budgets rise in line with inflation or more.

Just meeting Hunt’s commitment to increase defense spending from 2 per cent to 2.5 per cent of GDP would erase the almost £9 billion of leeway Hunt left in the forecast.

But making the numbers add up, at least for now, is the easy part.

The difficult steps are yet to come.

One of the “worrying trends” identified by OBR director Richard Hughes is the post-pandemic rise in levels of economic inactivity.

Some 9.3 million working-age adults who could work are not doing so, the highest number in 11 years.

Around a third of that total is due to long-term illnesses, the rest includes students and carers. Rising health-related inactivity has offset population growth due to migration, slightly reducing the OBR’s estimate of the size of the economy per capita in five years’ time.

The top-up to NHS spending announced by Hunt may help put some inactive adults back to work sooner. But it is a temporary solution to a much bigger problem.

As the population ages, spending on health and social care will continue to increase. It is expected to account for almost 45 per cent of daily spending on public services by 2028-29, according to the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS), compared to 26 per cent in 2000.

This leap, coupled with the limitations imposed by the fiscal straitjacket, will put enormous pressure on other unprotected departments such as the courts, local government and the environment.

They are likely to see real terms budget cuts of 3.4 per cent, the IFS warns.

Public sector efficiency savings, including long-awaited plans to make the NHS more digital, should help ease the pain, but only to a point.

Then there are baby boomers who are nearing retirement and who also tend to vote in large numbers.

In its latest fiscal risks and sustainability report, the OBR warned that as this cohort enters their golden years, state pension spending will be £23 billion higher in 2027-28 than at the start of the decade.

And that’s after raising the retirement age to 67 by then to curb rising costs.

This will inevitably raise questions about maintaining the “triple lock”, which guarantees the full increase in state pensions each year based on the increase in inflation, income or 2.5 per cent, whichever is greater.

H unt dodged this yesterday, but by maintaining his freeze on personal allowances (the £12,570 threshold where income tax applies) it is now just a matter of time before the full state pension of £11,502 becomes taxable as income increases.

The bad day could come in three years if wages grew just 5 percent a year.

It would be a mockery of fiscal policy.

It would also force whoever formed the current government to deactivate at least one time bomb.

But for now it remains cordoned off, along with other untapped demographic devices, hidden from public view, buried in a place where only the bravest politician dares to set foot.

Some links in this article may be affiliate links. If you click on them, we may earn a small commission. That helps us fund This Is Money and keep it free to use. We do not write articles to promote products. We do not allow any commercial relationship to affect our editorial independence.