Since they are sold in movie theaters and even game centers, it is reasonable to assume that slushies are completely safe for your children.

But this is not always the case, experts warn. Frozen slushies that contain glycerol (or E422) can make babies sick.

In fact, food safety chiefs are urging retailers not to sell products containing glycerol to children under 4 years old due to the inherent risk.

Just yesterday, a mother told how she feared for her four-year-old son’s life when he collapsed and became unconscious shortly after drinking a strawberry slushie in October.

However, that was not an isolated case.

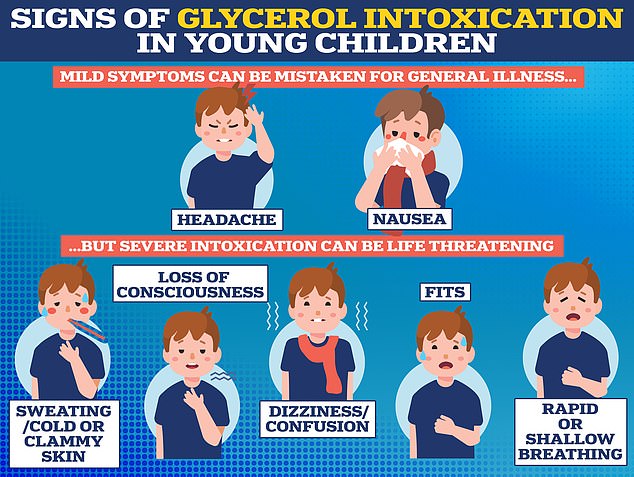

Could you spot the signs of glycerol poisoning in a child? While mild—it can cause headaches and vomiting—a heavy dose of the artificial sweetener found in slushies could send a child into life-threatening shock or hypoglycemia, a dangerous drop in blood sugar.

FSA bosses based their recommendations on a 350ml drink, similar to those available in shops and cinemas across the UK.

Last week, another mother shared a strikingly similar story of how her three-year-old son became sick from a raspberry-flavored slushie in January. He collapsed just 30 minutes later, became “limp” and suffered a seizure.

Both cases, detailed by MailOnline, have shed new light on the little-known risk of glycerol poisoning.

Glycerol provides the desired slushy effect, prevents frozen drinks from freezing, and acts as a sugar-free sweetener.

As for its use as a sugar substitute, experts have warned that a number of cases of glycerol poisoning may be an “unintended consequence” of the sugar tax.

When using sugar to make slushies, a minimum of 12g of sugar per 100ml is needed. However, only 5 g is needed when using glycerol.

While slightly toxic to humans, the amount typically contained in slushies is so small that regular consumption poses little danger to adults and older children.

Their bodies can process it before the glycerol levels build up and intoxicate them.

However, the same is not true for younger children.

Due to their much smaller body weight, the amount of glycerol needed to cause a serious health emergency is much less.

In theory, just a 350ml drink with the highest levels of glycerol could tip children under 4 over the “safe” threshold, according to the Food Standards Agency (FSA), which updated its glycerol recommendations. last summer after becoming aware of two separate cases of sick children.

At the time, it said slushy drinks containing glycerol should not be sold to children under 4 years old.

Children under 10 should also not be offered free refills on drinks, the FSA said.

Health authorities say the most likely scenario for glycerol poisoning comes from younger children rapidly consuming several E422-laden drinks, hence the FSA’s advice on refills.

Mild signs of glycerol poisoning include vomiting and headaches.

But experts warn that many parents can easily overlook the symptoms of children who just had a hailstorm.

Adam Hardgrave, head of additives at the FSA, said at the time the guidance was released: ‘While the symptoms of glycerol poisoning are usually mild, it is important that parents are aware of the risks, especially in high levels of consumption.

“Glycerol poisonings are likely underreported, as parents may attribute nausea and headaches to other factors.”

In extreme cases, glycerol poisoning can cause shock in children, where the circulatory system that pumps oxygen-rich blood throughout the body begins to fail, depriving vital organs of what they need to function.

Signs of shock include pale, cold, clammy skin, as well as sweating, rapid or shallow breathing, weakness or dizziness, nausea and possible vomiting, extreme thirst, and yawning and sighing.

Hypoglycemia, or low blood sugar, is another effect of glycerol poisoning.

Symptoms include hunger, dizziness, feeling anxious or irritable, sweating, shaking, tingling lips, heart palpations, fatigue and weakness, blurred vision, and confusion.

Beth Green, 24, from Nuneaton, Warwickshire, revealed her unconscious baby was hospitalized and feared he would die within an hour of drinking an ice-cold drink.

Beth became increasingly concerned when Albie began “hallucinating” and “scratching his face,” prompting the mother to rush him to the hospital.

In its most severe stage, hypoglycemia, typically associated with diabetes, can cause seizures and loss of consciousness.

Both shock and hypoglycemia can be life-threatening and are considered medical emergencies requiring urgent medical attention.

Two recent cases have highlighted how dangerous glycerol poisoning can be.

Beth Green, 24, from Nuneaton, Warwickshire, had her four-year-old son knocked unconscious after drinking a strawberry-flavoured slushy on a trip to the bowling after school in October last year.

She became increasingly concerned after Albie began “hallucinating” and “scratching his face”, prompting her to rush him to the hospital.

There doctors had to begin resuscitation because Albie’s blood sugar levels had fallen to dangerous levels.

At one point, his heartbeat became so slow that his parents thought he was going to die.

Doctors later told the couple that if they hadn’t taken Albie to the hospital right there, he would have died.

Beth’s account came just days after Scottish mum Victoria Anderson told how her three-year-old son Angus almost died in January after drinking a slushie last month.

The 29-year-old, from Port Glasgow, Inverclyde, had taken her youngest son, Angus, three, and his older brother shopping on January 4.

Not long after the trio ventured out, Angus ordered a raspberry-flavored slushy after spotting the bright pink frozen drink while at a corner store.

Unaware of the danger, Victoria bought the drink for her son, who had “never had a slushy before.”

About 30 minutes later, while in another store, the three-year-old boy unexpectedly collapsed and became unconscious.

Victoria said Angus’ body was limp and “stone cold” when paramedics attended the scene and tried to revive him after his blood sugar level dropped dangerously low.

Angus was rushed to Glasgow Children’s Hospital, where he remained unconscious for two hours.

Fortunately, both children received the medical care they needed.

Last summer, the FSA also asked slushie manufacturers to commit to adding only minimal glycerol to their products.

In that guidance, the FSA said it would be “monitoring” the extent to which the industry was following its advice and leaving the door open to take further action in the future.

Most UK slushies do not detail glycerol levels on their drinks packaging, but the British Soft Drinks Association (BSDA) says all its members have followed the new guidance.

A mother has issued an urgent warning about selling slushies to children after her young son suffered a “seizure” before falling unconscious after drinking the frozen drink.

Mother Victoria Anderson, 29, with father Sean Donnelly, 29, and sons Angus (left), 3, and Archie (right), 5.

The FSA advice was based on a slushie containing 50,000 mg/l glycerol.

Their alert was prompted by two previous cases of glycerol poisoning in Scotland, one each in 2021 and 2022.

Glycerol is also a component of foods such as pre-cooked pasta, rice and breakfast cereals, but in much smaller quantities than slushies. As such, these products are not considered dangerous for children.

Some brands have already removed glycerol from their recipes in response to FSA guidance, Slush Puppie being one of them.

Nichols, the company that owns the Slush Puppie brand, said it made this decision because it recognized that its drinks were “predominantly sold in locations popular with young children.”

Suppliers also list the popular Tango Ice blast brand slushie that contains E422.

The sugar tax was first introduced on soft drinks in 2018 and is estimated to have helped prevent thousands of hospital admissions for childhood tooth extractions.

It was designed to encourage manufacturers to reduce the sugar content in soft drinks, considered a determinant of cavities in children.

Many manufacturers turned to artificial sweeteners like glycerol to replace sugar without losing the sweet taste that attracted customers in the first place.

The sugar tax has been widely regarded as a success: a study in November last year estimated that it prevented more than 5,500 hospital admissions for childhood tooth extractions.

There have been multiple calls to introduce a similar tax on high-fat and high-salt foods to help combat Britain’s obesity epidemic but, so far, politicians have not had the courage to do so amid the cost crisis. life.