The collapse of an animal population in the United States has been linked to the deaths of thousands of children, a new study claims.

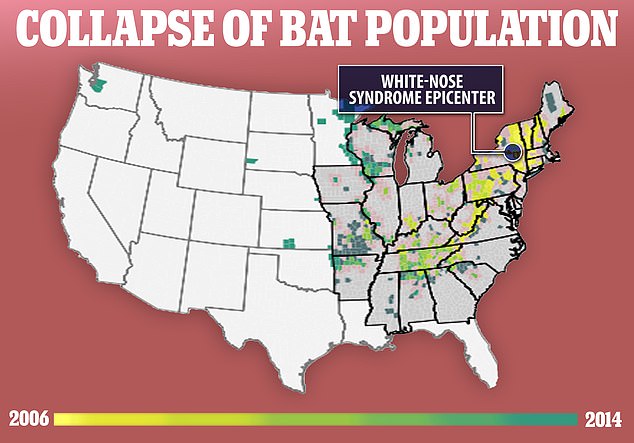

Millions of bats have been dying in critical agricultural areas across the country due to a deadly fungus that began spreading in 2006.

Farmers have long turned to the winged animals as natural pesticides because they eat at least 40 percent of their body weight in insects each night, but workers They have been forced to spray more toxic chemicals to make up for the loss.

Pesticides They have been linked to an increased risk of birth defects, low birth weight, and stillbirth.

More than 1,000 babies have died since farmers increased pesticide use in response to declining bat populations

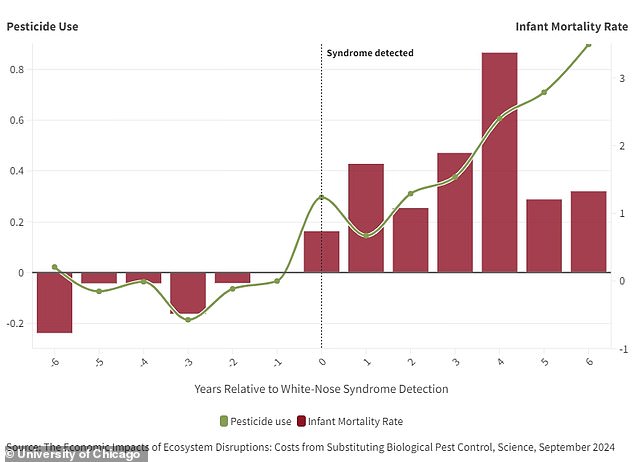

The new analysis linked the rise in toxic chemicals from 2006 to 2017 to the deaths of 1,334 infants in 1,185 counties in 27 states, mostly on the East Coast.

The selfAn invasive fungus, called Pseudogymnoascus destructans, causes a disease called white-nose syndrome (WNS) that has killed 6.7 million bats in the past 18 years.

Bats are known to eat at least 40 percent of their body weight in insects each day, many of which are crop pests.

But the deaths have forced farmers in affected counties to spray 31 percent more pesticides each year, the analysis found.

This has corresponded with a eight percent increase in infant mortality rate linked to pesticides.

According to the study, for every 1 percent increase in pesticides, the infant mortality rate increased by 0.25 percent.

The hardest-hit counties are primarily in the eastern and southern regions of the U.S., with New York, Michigan, Louisiana and Maine experiencing collapses in bat populations.

Eyal Frank, study author and adjunct professor at the University of Chicago, analyzed county-level data on detections of white-nose syndrome in bats, pesticide use by farmers and other health indicators, including infant mortality.

When farmers spray pesticides on their crops, wind and water can carry them far from the initial site, creating off-farm exposure for other area residents, according to the study published in the journal Nature. Science.

The highest levels of agrochemical contamination are detected during the peak of the agricultural season, which runs from April to September.

Pesticides have been linked to negative health effects, including increased risk of chronic diseases such as cancer, neurological disorders and developmental delays, and can cause acute poisoning.

An estimated 6.7 million bats have died from contracting an invasive fungus that causes white-nose syndrome.

White-nose syndrome causes dehydration, starvation and death in bats. It originates from a fungus that was found in New York in 2006 and has since spread to 38 states in the United States.

Every time farmers increased pesticide use by one percent, the infant mortality rate increased by 0.25 percent.

Frank said the increase in pesticide use by farmers was correlated with the rise in the domestic infant mortality rate, excluding those who died in accidents or homicides.

“Bats have gotten a bad reputation as something to be afraid of, especially after reports of a possible link to the origins of Covid-19,” Frank said.

“But bats add value to society in their role as natural pesticides, and this study shows that their decline can be harmful to humans.”

The fungus can be spread by infected bats, but can also be transported from cave to cave on human clothing and equipment.

It can grow on a bat’s ears, nose, and wings and can invade deep skin tissue, causing WNS resulting in dehydration, starvation, and death.

Pseudogymnoascus destructans is native to Europe and Asia, where bats appear to be unaffected, but is believed to have been first introduced into upstate New York by a tourist in 2006.

It was found in a cave connected to a commercial cave that receives 200,000 visitors a year.

Since the fungus was discovered, it has spread rapidly at a rate of 200 miles per year, affecting a total of 38 states so far, according to the Centers for Biological Diversity.

It grows best in moist caves where bats typically hibernate and thrives in cool temperatures around 57 degrees Fahrenheit.

There are 13 confirmed bat species that have been infected with WNS, including long-eared, little brown, and tricolored bats.

The northern long-eared bat has been the hardest hit by the disease, with its population declining by as much as 99 percent in several eastern U.S. states.