When undercover CIA agent ‘Anthony Lagunas’ was granted an audience with President George W. Bush, it should have been a proud moment for the star agent.

It is an honour rarely bestowed on rank-and-file spies, but one that was given to Lagunas (not his real name) in recognition of his extraordinary efforts to infiltrate al-Qaeda killer cells after the 9/11 attacks.

Instead, the notorious “ladies’ man” seemed distant, disillusioned and only cared whether he could “sit next to an attractive girl on the flight,” former colleagues said. Rolling Stone.

In retrospect, agents believe Lagunas’s ambivalence was one of the first signs that he was beginning to lose his way: calloused by his years in the field and pushed to the edge by his handlers.

It was the beginning, they said, of his tragic struggle with post-traumatic stress disorder and depression, which culminated in his death under mysterious circumstances in a hotel room in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

CIA undercover agent ‘Anthony Lagunas’ was a star operative during the post-9/11 War on Terror, when spies were sent to infiltrate jihadist terrorist groups. Pictured: Fighters from the Al Nusra Front, al-Qaeda’s Syrian affiliate, drive through the northern Syrian city of Aleppo, waving Islamist flags as they head to the front line, on May 26, 2015.

Lagunas was one of a new wave of CIA agents sent to bed down with radical Islam after the 9/11 attacks.

His legacy has divided opinion. Some hail him as a “hero,” others dismiss him as a man who spent his time “wasting time,” “smoking and joking,” “chasing women.”

But most of those who knew him say his sad disappearance is now a “cautionary tale” about the tensions faced by undercover CIA agents who, if not killed by the enemy they are supposed to befriend, are left at the mercy of their innermost demons.

More than two dozen former CIA officials spoke on condition of anonymity to unravel an extraordinary story and ask whether it was really accomplished at the cost of one man’s life.

Lagunas lived undercover for about five years in the Middle East as an Islamic radical, infiltrating extremist groups while sporting a distinctive thick beard and a needle-shaped scar on one arm caused by an old barracuda bite.

He was one of the first undercover agents the CIA threw into the arms of terrorists as part of a momentous shift in post-9/11 strategy.

Instead of roaming around stealing secrets from foreign governments, the security services realized they needed to conduct their operations “outside the embassy” in order to infiltrate terrorist groups.

Lagunas was just a trainee at the agency when the plane crashed into the towers.

But soon after the attacks, he and a few others were removed from the CIA’s regular training program.

At first, others within the agency were unsure whether he had been transferred to a top-secret initiative or simply pushed out of the agency.

“It was 50-50,” said a former agency official. Rolling stone.

At the time, Lagunas was known as a somewhat wild man, he said. He drank heavily and was “a bit of a womanizer, a very womanizer,” the former official recalled.

Lagunas spoke some Arabic, but perhaps it was his unique personal qualities that interested his superiors.

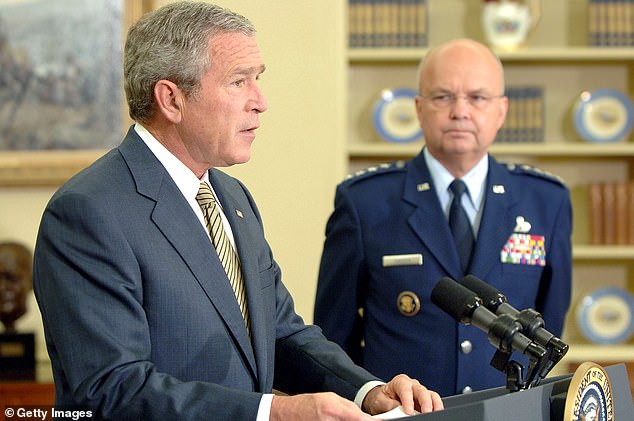

President George W. Bush speaks as former National Security Agency Director Gen. Michael Hayden looks on during a personnel announcement May 8, 2006, in the Oval Office of the White House in Washington, D.C. Both men were instrumental in leading America’s war on terrorism following the Sept. 11 attacks.

“He had the ability to distance himself,” recalled another former senior agency official.

“I don’t want to say it’s a split personality or anything like that, but the ability to detach from one reality and adopt a second reality to the point of not acting like it but being it, is a skill that cannot be taught.”

Lagunas’ ability to dissociate was “extraordinary,” the former official added. But his strength was also his weakness. It also became the root of his struggle to define where his undercover persona ended and his real life began, as he delved deeper into the world of jihadist terror.

It is unclear exactly where Lagunas spent much of his time, but for at least part of his mission he was stationed at a madrasa in Cairo, as well as in Saudi Arabia, studying the Koran.

He was not the only undercover agent to infiltrate radical Islam, but he remained undercover longer and with fewer interruptions, according to former officials.

Lagunas also seemed to be up to the task.

“He looked like he had come straight from a central Hollywood casting call,” recalled a former senior agency official.

“An Arabic-speaking Salafi with a ‘killer beard,’ dressed in traditional garb, a typically American Midwestern white boy turned jihadist,” wrote Rolling Stone magazine.

But as much as he accepted his role, there is no consensus on whether the information he collected was actually useful.

A sector of the CIA considered that the only useful information was that which could lead them to capture or kill Al Qaeda leaders and other terrorist agents.

For them, the “legend” of Lagunas stemmed in part from “the fact that he was a white man” living undercover as a Muslim radical, rather than from any actual intelligence he had uncovered.

Lagunas was simply CIA bragging, another former official said. “They had a map of the world with pins indicating where people were deployed, and that was one of their big, proud debriefing moments: ‘Look where we’ve put people,’ the former agency official told Rolling Stone. ‘Oh, we have a guy in the Maldives? Why?’ “I don’t know, but we have a guy in the Maldives.”

The legacy of ‘Lagunas’ has divided opinion. Some hail him as a ‘hero’, but others dismiss him as a man who spent his time ‘wasting time’, ‘smoking and joking’, ‘chasing women’.

According to four former officials, Lagunas infiltrated al-Qaeda, but only its broader network, not its leadership.

Three other former officials said that while Lagunas did indeed gain entry into radical Islamist circles, he never actually penetrated al-Qaeda.

However, some CIA sources said his achievements were truly impressive.

“He was very, very talented and very skilled at acquiring information that was incredibly useful to the U.S. government,” said another former senior official.

Details of what he provided are unknown and former agency officials declined to release details.

In the end, his work caught up with him.

Former colleagues said the CIA would never take proactive steps to protect agents like Lagunas. “They’re never going to say ‘enough’ for you,” said one.

Increasingly, Lagunas seemed unable to distinguish between his undercover life and his own.

The warning signs were not only in his lackadaisical reaction to his audience with the President, but in the late 2000s, CIA officials decided it was time to bring him home.

But this only seemed to make matters worse.

Former colleagues said the CIA would never take proactive steps to protect agents like Lagunas. Pictured: A view of the main entrance to CIA headquarters in Langley, Virginia

Lagunas was given a domestic job in Los Angeles. He continued to operate as an undercover intelligence agent, but this time in the entertainment industry.

It is unclear what work he did in Hollywood, but former colleagues said he was “never the same” after returning to the United States.

Although they were not privy to the details of his overseas posting, they knew “it was tough, he got into a lot of trouble, it was bad, it was hard on him, (and) it was all screwed up,” one former official said.

“It came out of nowhere and had no reception,” said another. “Ah, what did you do? Well, that’s great. Make sure you log in at nine, mate.”

In the fall of 2016, his colleagues received news that Lagunas had died suddenly in a hotel room in Kuala Lumpur.

The circumstances are murky.

Drug and alcohol abuse likely contributed, Rolling Stone reported, as did extreme depression and post-traumatic stress disorder.

“It was stress that led to the death,” said one former official. “The stress of life, what happened.”

“Without commenting on specific claims by any individual, with respect to our workforce, the CIA takes the mental, physical, and professional health of our officers very seriously, and in recent years has significantly expanded the resources available to our workforce,” a CIA spokesperson told Rolling Stone.

“We have no greater obligation than to guarantee the safety and well-being of our workers.”

(tags to translate)dailymail