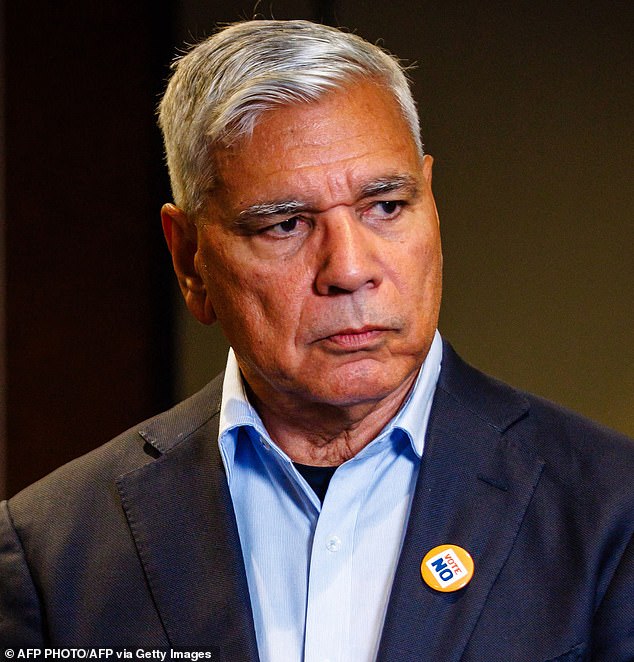

No and Warren campaign leader Mundine says the new Indigenous Voice to South Australia’s Parliament is a stealth way to introduce the rejected federal proposal at state level.

The first 46 elected members of six regional Voices were announced last week following an election in which only 2,748 votes were cast from 27,534 Indigenous people on the electoral roll who were eligible to vote in South Australia.

Mundine, who led the successful fight against the federal Voice of Parliament proposal, defeated in a referendum last year, says the low turnout shows that the majority of indigenous people “were not interested” in the body.

No campaign leader Warren Mundine says South Australia’s new Indigenous Voice to Parliament is undemocratic and only exists to provide cushy jobs for an Aboriginal elite.

“What’s happened there is all these corporations and institutions, they’ve been captured by this elite group of Aboriginal people who, frankly, are looking for work,” he told WhatsNew2Day Australia on Thursday.

Mundine, director of the Indigenous Forum at the conservative Center for Independent Studies think tank, asked how Voice members could claim to represent Aboriginal people when one was elected with just six votes and another garnered just 35.

“That’s just ridiculous,” Mr. Mundine said.

‘We are spending all this money. We’re spending money on elections, we’re spending money on meetings, transporting people to different conferences and that kind of thing. It’s costing us a fortune.

‘Now they are simply imposing these representative bodies on the people. It’s just silly, it’s just weird.

“They represent no one and receive enormous salaries and all the benefits that come with them.”

The South Australian Government will spend $10.3 million on Voice over the next three years and regional Voices will elect two members each to represent them on a 12-person direct advisory body on legislation.

Voice members will receive stipends of $3,000 to $18,000, attendance fees of $206 per meeting plus per diem for travel, lodging, meals and $1,000 for a new laptop.

Crowds gathered outside South Australia’s Parliament last year to welcome legislation creating the Voice.

Mundine said that since the federal Voice proposal was rejected by more than 62 percent of voters in October, he believed the creation of state-based Voices was a slap in the face to the electorate.

“They don’t believe in the democratic process,” he said.

‘They don’t believe in democracy, that’s obvious to me. People have spoken up and they’ve just ignored it.’

He said his experience of campaigning in Australia in the run-up to the referendum was that, regardless of whether they voted Yes or No, Australians wanted the problems of indigenous Australia to be solved.

“They want practical results, they don’t want a group of people sitting around a table forever,” he said.

“They’re just sick and tired of this nonsense that keeps happening.”

‘We’ve set up these committees since (former Labor Prime Minister) Gough Whitlam and what happened? Nothing.’

“Let’s go back to basics,” Mr. Mundine said.

“They have to be practical results, that people get to schools, get educated, get jobs, get housing, that the entire community is safe where there is law and order.”

South Australian Aboriginal Affairs Minister Kyam Maher called the Voice vote “a success” despite the low turnout.

“More than 2,000 South Australian First Nations people voted for South African First Nations Voice to Parliament in a successful first election,” Mr Maher said in a statement.

‘This strong first result provides a platform for the Voice to grow, particularly with future elections coinciding with regular state elections.

“This is also in line with the range of votes cast in the South Australian elections for the former Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission in the 1990s.”

Winning Central Region candidate April Lawrie told ABC the result of the federal Voice referendum caused a lot of uncertainty for the state body.

While Ms Lawrie admitted there was “a lot of work to do in terms of promoting this”, she called for the Voice to be “given a chance” and believed it would “gain momentum”.

‘It is the first one. “Give our community a chance to see how this goes,” she said.

“Once our community is informed and engaged with the concept of Voice and the reality that it is here, this is our opportunity now, as a collective and representative Voice, to find ways in which we spread that information.”

Lawrie said she was “really excited” to become an elected representative.

“It’s quite significant because I think for South Australia we are the first jurisdiction to create… a First Nations Voice,” he said.

Crowds gathered outside South Australia’s parliament to welcome the creation of Voice when it was passed in March last year.