Table of Contents

One hot Saturday in 1979, while mowing the lawn at my family’s home in Washington, my wife Tricia called me on my landline.

The familiar booming, Irish-tinged voice of Joe Coyne, then spokesman for the Federal Reserve, America’s central bank, was speaking on the phone.

‘Alex, can you come to the Federal Reserve at 4 p.m.? “Maybe I have something for you,” he said gruffly.

The call was a shock. For several months, as The Guardian’s US correspondent focusing on the economy, I had routinely called the Federal Reserve to ask what it proposed to do about the dollar’s decline in currency markets. The answer was always the same: “We never talk about the exchange rate.”

But after a strategy he had developed in London, during the sterling crisis of 1976, when he daily called the UK Treasury and the Bank of England in the hope of gaining wisdom about the collapse of the pound, the natural thing was call the Federal Reserve.

The Carter administration’s handling of the oil crisis and high inflation in the 1970s, after the Yom Kippur War, was disastrous.

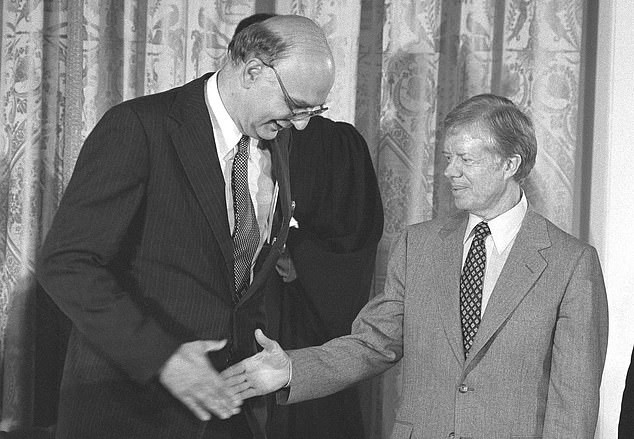

Passionate: Jimmy Carter, who died on December 29 at the age of 100, has been widely praised as America’s most distinguished post-president.

Carter attributed the incident to “unrest” over energy use among the American people. Maybe he was right.

But the consequences were alarming. Inflation soared to 7.6 percent in 1978 and 11.3 percent in 1979.

The dollar fell 40 percent against the Japanese yen, 35 percent against the Swiss franc and 13 percent against the German mark. In nine months it fell 19 percent against a basket of currencies.

Desperate measures were needed. The US Treasury arranged swap lines worth $22 billion with major central banks.

He began a series of gold auctions, selling 750,000 ounces from his reserves at Fort Knox.

And like Britain in 1976, it even borrowed from the International Monetary Fund (IMF), withdrawing funds from US holdings worth $3 billion.

It was the lowest point of Jimmy Carter’s management of the economy. Trust at home and abroad was shattered and only dramatic action would suffice.

Carter, defying the traditional independence of the Federal Reserve, decided to fire the struggling president, the former industrialist and loyalist Democratic fundraiser, G. William Miller.

Parachuted in his place was Paul Volcker, an experienced figure who, as Treasury undersecretary for monetary affairs in 1976, played a key role in collaborating with the IMF in rescuing the pound three years earlier.

He was considered someone who could be trusted to solve a financial problem.

The dramatic events of that summer come vividly to mind as the United States buries Jimmy Carter in a state funeral today.

The 39th president has been widely praised as America’s most distinguished “post-president.” He continued his campaigns for human rights and democracy around the world and for better housing in the United States almost until his death at the age of 100.

I remember interviewing him at his Atlanta-based Carter Center for Peace in 1989, as I was ending my decade in the United States.

He was as passionate as ever about building on the Camp David accords between Israel and Egypt, which he had negotiated as president.

However, it is extraordinarily difficult to reconcile Carter’s passion for peace and disease eradication among Africa’s poor with the failed presidency that imploded.

Lasting legacy: Carter (right) with Paul Volcker (left), who parachuted in as Federal Reserve chairman

Back in 1979, that call from Joe Coyne to the Federal Reserve, when I, along with a Swiss correspondent and another writer, were the only foreign journalists present, was a truly historic moment.

It was a turning point for economic policy and, as it happened, for American politics.

Volcker, tall and slightly stooped, with a booming voice, sat at the end of the long mahogany table where members of the Federal Reserve’s open markets committee that sets interest rates traditionally deliberate.

To end Carter’s agony that afternoon, the unelected Volcker recast the American approach to ending the specter of inflation and restoring the dollar’s credibility.

Gone was the traditional Democratic policy of wages and prices, which had failed in the Britain of James Callaghan and Denis Healey, and in came an early version from the guru of Chicago School monetarism, Milton Friedman.

Volcker began raising official interest rates, first to 11 percent and then to 20 percent by the end of the year.

He decided to focus on the money circulating in the economy and impose a surcharge on credit card transactions in an economy where people were living beyond their means.

This was equivalent to hitting the brakes.

The “Volcker moment” proved seismic for the American economy, Jimmy Carter’s presidency, and American politics.

On the eve of the 1980 campaign for the White House, it sealed Carter’s fate.

The surcharge and rising interest rates saved the dollar and defeated inflation.

They also meant a deep recession, which did not fully end until 1982, and paved the way for the arrival of Ronald Reagan, whose rhetoric ensured a landslide Republican victory.

Carter’s implosion taught Democrats a lesson that was cleverly adopted by

Bill Clinton in 1992, after 12 years of Republican government; his simple slogan “the stupid economy” would become the magnet for all future White House incumbents.

- Alex Brummer, City Editor of the Daily Mail, was The Guardian’s Washington correspondent from 1979 to 1989.

DIY INVESTMENT PLATFORMS

AJ Bell

AJ Bell

Easy investing and ready-to-use portfolios

Hargreaves Lansdown

Hargreaves Lansdown

Free Fund Trading and Investment Ideas

interactive inverter

interactive inverter

Fixed fee investing from £4.99 per month

sax

sax

Get £200 back in trading fees

Trade 212

Trade 212

Free trading and no account commission

Affiliate links: If you purchase a This is Money product you may earn a commission. These offers are chosen by our editorial team as we think they are worth highlighting. This does not affect our editorial independence.

Some links in this article may be affiliate links. If you click on them, we may earn a small commission. That helps us fund This Is Money and keep it free to use. We do not write articles to promote products. We do not allow any commercial relationship to affect our editorial independence.