A controversial linen shroud — believed by some to be the one in which Jesus Christ was buried — has baffled the world since it was made public in the 14th century.

This cloth, which we know today as the Shroud of Turin, first appeared around 1355 AD in the small French village of Lirey, attracting pilgrims who marveled at its unusual “photographic negative” image of a crucified man.

But there are few official records of the Shroud before this time, when it was brought to the dean of the village church by the French knight Geoffroi de Charny.

Skeptics have long pointed to this millennia-long gap in the Shroud’s early history as evidence of forgery, along with radiocarbon dating from 1989 that supports this idea.

But with new research casting doubt on radiocarbon dating, could the Shroud of Turin have a “secret history” that explains its long time outside of historical records?

Markwardt argues that early persecuted Christians concealed their faith out of fear of persecution, a historical fact known as the “Discipline of Secrecy.”

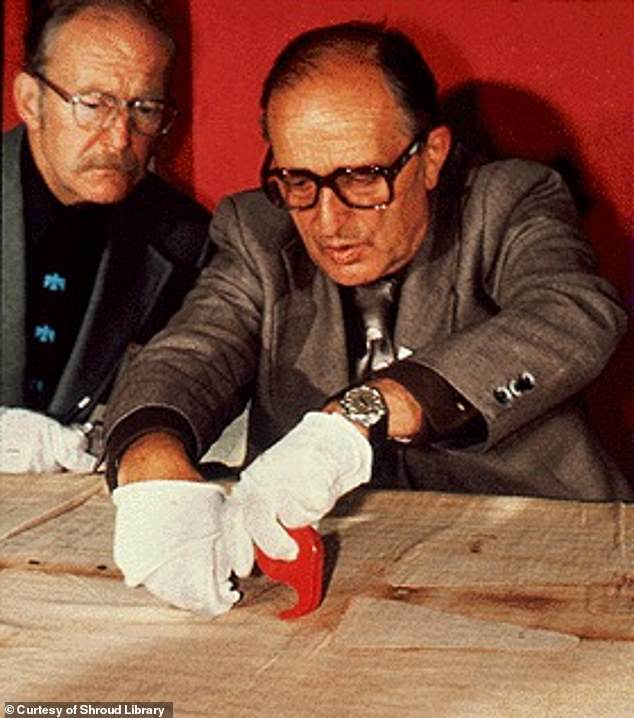

It was not until 1978 that the first physical samples of the cloth were permitted to be taken, which was done by using adhesive tape to carefully remove particles from the front fibres. Dr Max Frei, a Swiss criminologist, can be seen taking samples from the shroud.

That’s the idea behind a provocative book, ‘The Hidden History of the Shroud of Turin’, by American lawyer and author Jack Markwardt.

Markwardt argues that there are good reasons why the Shroud was initially hidden and that this mysterious cloth could be an authentic relic of the Passion of Christ.

Was the Shroud initially hidden out of fear?

In his book, Markwardt details how early Christians hid their faith for fear of persecution, a historically documented practice known in Latin as Arcane Discipline or the ‘Discipline of Secrecy’.

This custom of the 4th and 5th centuries in the early Church dictated that certain doctrines were to be kept secret from non-believers and even from people who were still learning the faith.

In ‘The Hidden History of the Shroud of Turin’, American lawyer Jack Markwardt argues that there are good reasons for the Shroud to have been initially hidden in early Christian history.

The rules of Arcane DisciplineMarkwardt argues that this would have meant that the embryonic Christian church would have hidden the existence of the Holy Shroud.

“When, shortly after Jesus’ death, his disciples, now organized as a Church, faced religious persecution,” he writes.

‘They obeyed his directives by resorting to secrecy and hiding from non-believers every pearl of the new faith, including the Holy Shroud of Turin.’

But although the Shroud remained hidden, allusions to a very similar relic can be found in several ancient sources, according to Markwardt, providing clues as to its safekeeping and whereabouts during this period of intense secrecy.

The author and lawyer claims that Saint Peter himself took the Shroud with him to Antioch, an ancient Greek city on the banks of the Orontes River, today the Republic of Turkey, with a historic role in the medieval Crusades.

From there, the Shroud is believed to have ended up hidden (again) deeper within the walls of Antioch, above the city’s Cherubim Gate.

Markwardt argues that early Christians hid the shroud out of fear.

As evidence, Markwardt cites the apocryphal “Gospel of the Hebrews,” which refers to “the Lord” giving “the linen cloth to the priest’s servant.”

Was the Shroud of Turin “Hidden in Plain Sight”?

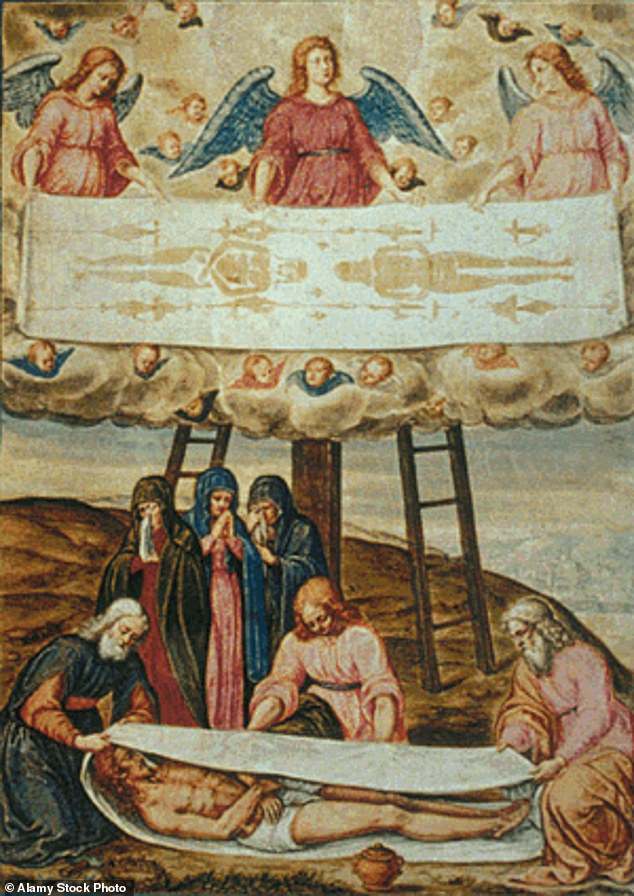

Mysteriously, during this period when Markwardt claims the Shroud was hidden within the walls of Antioch, the bearded image on the cloth began to influence artwork depicting Jesus, who had previously been shown as a beardless youth.

Why then, suddenly, in works of art from the 3rd to the 5th century, does Jesus begin to appear in Christian art sporting a beard?

Author Ian Wilson has suggested that the writing from that period on the so-called “Image of Edessa” may actually have been the Holy Shroud itself, folded four times and presented solely as an image of Christ’s face.

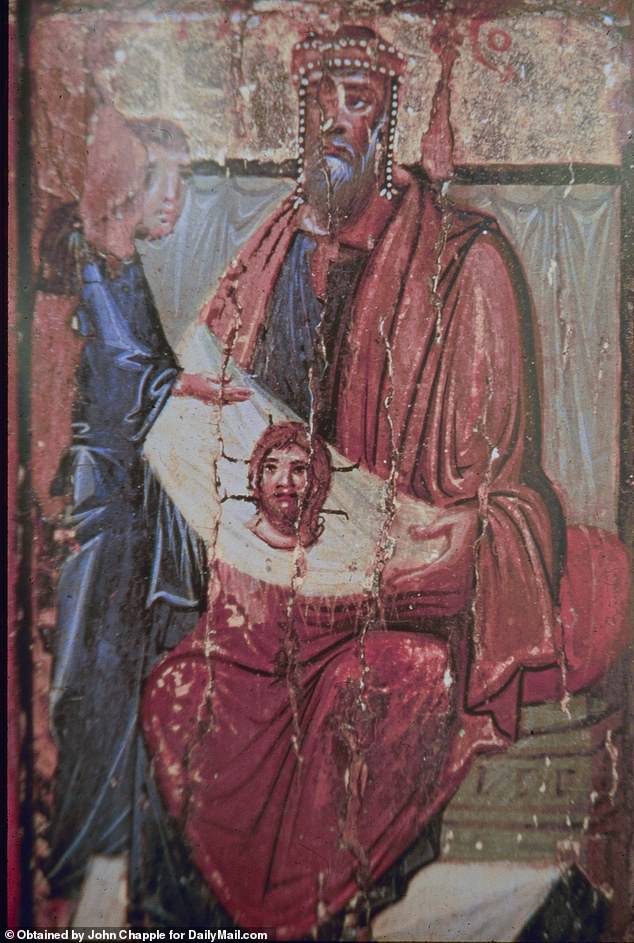

The Edessa image supposedly dates back to an ancient king, King Abgar of Edessa, in what is now Urfa in Turkey, who requested Jesus to cure him of an illness.

“Four texts and one work of art confirm that Pope Eleutherius, upon receiving the request of (King) Abgar the Great to convert to Christianity,” writes Markwardt, not only “performed his baptism” but “ordered that the Holy Shroud of Turin be displayed to him.”

Markwardt argues that early Christians hid the shroud out of fear.

The hope of the Catholic Pontiff, according to the author, was to reinforce the king’s confidence in his conversion, “to affirm him in his decision to be baptized.”

A more mythologized story, explored by the National Catholic RegisterHe suggested that one of King Abgar’s recent ancestors had asked the still-living Jesus to visit him in order to heal him through one of his famous miracles.

According to this legend, Jesus refused, but sent a letter containing a picture of Jesus that, according to various accounts, had been painted or “made by God.”

Other accounts also imply that the Shroud was exposed in the region in the decades and centuries following the reported date of Christ’s crucifixion.

In the Sermon of Athanasius, supposedly written by a fourth-century bishop of Alexandria, there is a reference to “an image of the Lord Jesus Christ… painted upon a board of tables (which) contained the image of our Lord and Savior in its entirety.”

As Markwardt argues: “The Shroud is the only full-length ‘holy image of our Lord and Savior’ associated with the Passion of Jesus that can be dated even to that period.”

“Assuming this text is truly authentic and reliable,” he said of the sermon text, “it is clearly connected with the flight of the Church from Jerusalem.”

‘Those who claim that the Shroud of Turin did not exist or was hidden at that time,’ Markwardt argues, ‘have an obligation to identify a full-length “sacred image of our Lord and Savior” associated with the Passion of Jesus, distinct from the Shroud of Turin, to which the Sermon of Athanasius could possibly refer.’

Was the history of the Shroud deliberately hidden?

Markwardt claims that much of the doubt surrounding the origin of the Shroud may have arisen from stories invented by Justinian I, as part of the Eastern Roman Emperor’s efforts to obtain the Shroud for himself.

Justinian deliberately spread a story about an image of Jesus’ face that originated in the small Cappadocian town of Camulania, the lawyer said, and this account gave fodder to people who wanted to deny the Shroud’s ancient origins.

“By creating the illusion (…) Emperor Justinian I effectively and forever erased the apostolic provenance of the relic,” writes Markwardt, “its entire ancient history and its five-century affiliation with the Church of Antioch.”

“This greedy, rapacious and scheming Byzantine emperor,” he said, “more than any other person, is responsible for the historical darkness that currently surrounds the Shroud of Turin (and) for the doubt that currently surrounds its authenticity.”