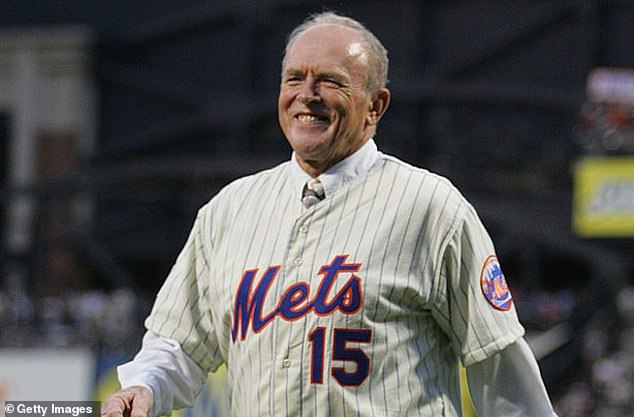

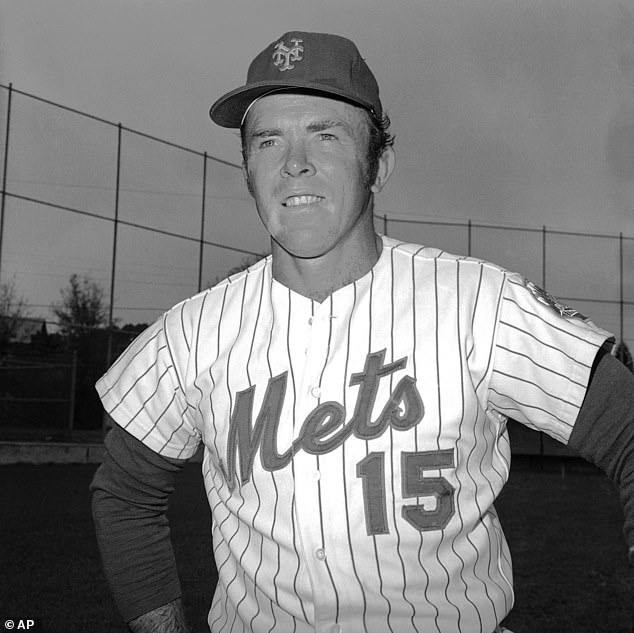

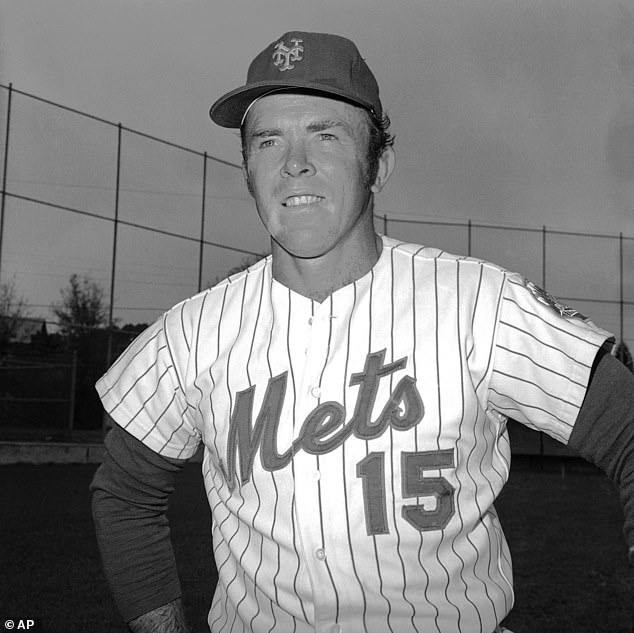

Jerry Grote, the catcher who helped transform the New York Mets from perennial losers to 1969 World Series champions, died Sunday. He was 81 years old.

Grote had suffered heart problems and died at the Texas Cardiac Arrhythmia Institute at St. David’s Medical Center in Austin, Texas, Mets spokesman Jay Horwitz said.

Grote had been scheduled for a procedure and died of respiratory failure during the procedure, Horwitz said.

A two-time All-Star, Grote played 16 seasons in the major leagues and batted .252 with 39 home runs and 404 RBIs.

“The backbone of a young Mets team that captured the heart of New York City,” Mets owner Steve Cohen and his wife Alix said in a statement.

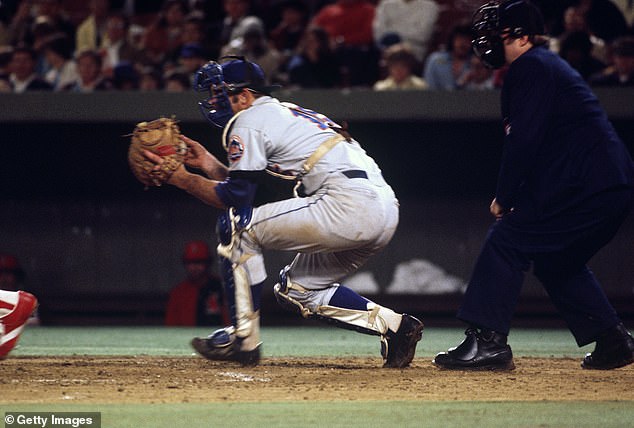

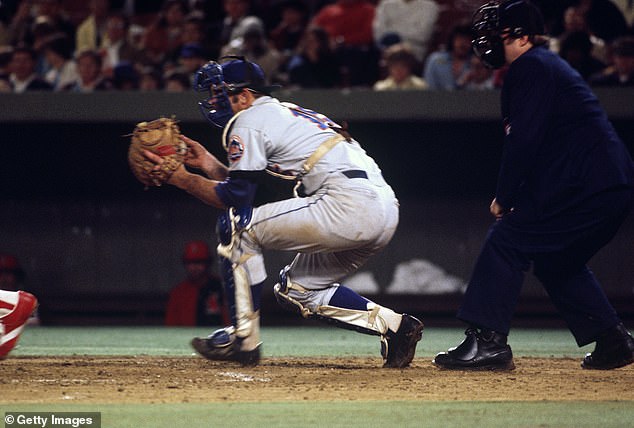

Jerry Grote was the Mets’ catcher in their 1969 World Series victory over the Orioles.

Grote has remained active as a Met for decades, recognized as a member of the ‘Miracle Mets’

Grote had played two seasons with the Houston Colt .45 when the Mets acquired him in October 1965 to name a player, who turned out to be pitcher Tom Parsons.

Launched as an expansion team in 1962 to replace the defunct New York Giants and Brooklyn Dodgers, the Mets finished ninth or 10th in their first seven seasons before a notable turnaround in 1969.

“We weren’t supposed to do anything,” Grote said at the 50th anniversary celebration in 2019. “And we did it all.”

Grote assembled a young pitching staff led by Tom Seaver, Jerry Koosman and Gary Gentry. The Mets surpassed the Chicago Cubs and moved into first place for the first time in their history on September 10.

They went 100-62 to win the NL East by eight games, then swept Atlanta three games in the first National League Championship Series and beat heavily favored Baltimore in a five-game World Series.

“He was the glue that held the staff together,” Mets star Cleon Jones said in a statement.

Grote was called up to the All-Star Game for the first time in 1968, starting in the National League in the All-Star Game at the Houston Astrodome and batting .282.

He hit .252 with six home runs and 40 RBIs in 1969, starting 100 games behind the plate. The night the Mets took the division lead, he caught all 21 innings in a doubleheader sweep in Montreal.

Grote, right, hugs pitcher Jerry Koosman as Ed Charles after the Mets won the 1969 World Series.

Grote had played two seasons with the Houston Colt .45 when the Mets acquired him in 1965.

Grote caught every inning of the postseason. He hit a two-out single off Dave McNally in the ninth inning of Game 2 of the World Series to put runners on the corners, and Al Weis followed with an RBI single that lifted the Mets to a 2-1 victory.

Grote doubled off Dick Hall leading off the 10th inning of Game 4, and pinch-runner Rod Gaspar scored on JC Martin’s sacrifice bunt for another 2-1 victory.

“Without Jerry, we wouldn’t win in 1969,” Mets outfielder and first baseman Art Shamsky said in a statement. ‘It’s as simple as that.’

Grote was the Mets’ leading catcher from 1966 to 1971, then began splitting time with Duffy Dyer in 1972. He helped the Mets win another National League pennant in 1973. Praised for his defense, Grote was part of his second All-Star Game in 1974.

“He was the best catcher I ever threw to,” Mets pitcher Jon Matlack said in a statement.

Grote was not a great power hitter throughout his career, only hitting 39 home runs and collecting 404 RBIs.

Following the emergence of John Stearns, Grote was traded to the Los Angeles Dodgers in August 1977, became a free agent after the 1978 season, and then retired.

He changed his mind three years later and in 1981 parted ways with Kansas City and the Dodgers. He had a career-high seven RBIs on June 3, 1981, hitting a grand slam off Seattle’s Ken Clay.

Gerald Wayne Grote was born in San Antonio on October 6, 1942.

He was a three-sport star at MacArthur High and attended Trinity University in San Antonio, where he gained skills as a catcher with the help of former Major League player Del Baker, a team advisor.

Grote was not a power hitter, he only hit 39 home runs, but he was a great defensive catcher.

In the days leading up to the amateur draft, Grote was signed by Houston scout Red Murff in 1962 and made his major league debut on September 21, 1963.

Grote came on in the fifth inning against Philadelphia at Colt Stadium and hit a sacrifice fly off Dallas Green in his first plate appearance.

Grote was traded to the Mets after Murff moved to New York and recommended his acquisition.

Grote, twice divorced, is survived by his third wife, Cheryl; son Jeff; daughters Jennifer Jackson and Sandy Deloney; and his stepdaughter Laurel Leudecke, according to the Mets.