British heart patients will soon be given heart valves that grow naturally inside the body, marking a significant advance in the treatment of heart disease.

An initial group of more than 50 patients will receive temporary valves made of fibers that will act as “scaffolds” that, when implanted, will integrate with the body’s cells.

Over time, the scaffolds dissolve, leaving a living valve composed entirely of the patient’s own tissue.

When heart valves become diseased, they can harden or leak, increasing the risk of heart failure, stroke, or heart attacks.

Existing valve replacement options for patients have significant drawbacks.

Valves taken from cows, pigs or human tissue and implanted in the patient only last about a decade and can still be rejected by the body’s immune system. Mechanical valves require patients to take medications throughout their lives.

Current treatments are extremely challenging for children born with heart defects, as the valves do not grow with their bodies and must be replaced several times before they reach adulthood.

But the new valves can grow as the child grows and become one with the patient’s body.

The project is led by Professor Sir Magdi Yacoub (pictured), a renowned cardiac surgeon.

An initial group of more than 50 patients will receive temporary valves made of fibers that will act as “scaffolds” that, when implanted, will integrate with the body’s cells.

Professor Yacoub carried out the first heart-lung transplant in the UK at Harefield Hospital, north-west London (pictured).

The project is led by Professor Sir Magdi Yacoub, a renowned cardiac surgeon in his 80s who carried out the UK’s first heart and lung transplant at Harefield Hospital in north-west London.

Each year, approximately 13,000 heart valve replacements are performed in England and 300,000 worldwide, and the numbers are increasing every year.

The new living valve could transform the lives of these patients by eliminating the need for repeat surgeries and reducing the risk of rejection.

Dr Yacoub told the Sunday Times: ‘I always say nature is the best technology. It is far superior to anything we can do. Once something is alive, whether it’s a cell, tissue, or (living valve), it adapts on its own. Biology is like magic.’

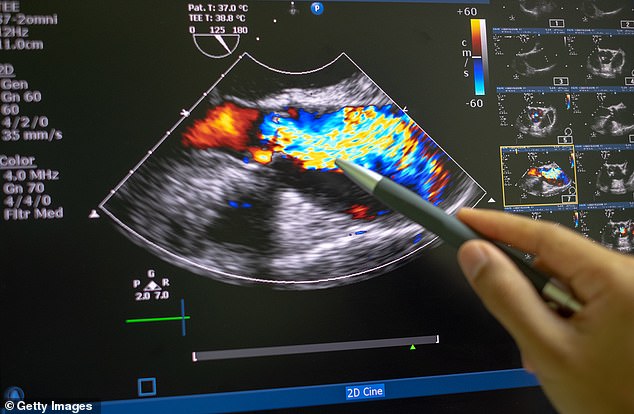

Research published in Nature Communications Biology showed promising results in sheep.

In just four weeks after implantation, more than 20 types of cells, including nervous and adipose tissue, were found in the right places, mimicking a natural heart valve.

Unlike previous attempts, this project, led by Heart Biotech at Harefield Hospital, has successfully encouraged the growth of nerve cells in the valve.

Within six months, the structure is made up entirely of the patient’s living cells, and after one to two years, the structure dissolves, leaving a fully functional heart valve that grows with the patient throughout their life.

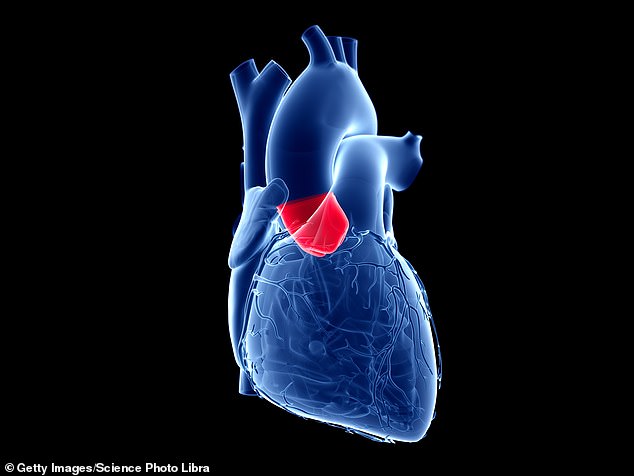

Research published in Nature Communications Biology showed promising results in sheep. In the photo: Illustration of the aortic valve.

Human trials with between 50 and 100 patients, including children, will begin in 18 months.

The trials will compare the new living valve with conventional artificial valves and will involve an international team of experts from institutions including University College London, Great Ormond Street Hospital and medical centers in New York, Italy and the Netherlands.

Dr Sonya Babu-Narayan, associate medical director at the British Heart Foundation, hailed the development as “the holy grail” for heart valve surgery.

She said: “It’s still early days, but if further research shows the approach is successful in humans, many people around the world could live well for longer without the need for repeated heart valve procedures.”