On January 24, 1933, a cartoon showing Adolf Hitler standing in the graveyard of his failed political movement appeared in a German newspaper. He was depicted as a Hamlet figure, holding and contemplating his own skull among a forest of swastika-shaped tombstones.

If only!

Germany’s deluded non-Nazis had managed to convince themselves that the danger had passed. Although Hitler had traveled 40,000 miles by plane during the recent election campaign, showing off all his oratory tricks in packed halls across the country, his National Socialist Party had not achieved anywhere near the necessary 51 percent of the vote. nationals for a parliamentary majority.

In the Reichstag elections on November 6, two-thirds of German voters rejected him. He had lost two million votes since the previous election in July. And his party was bankrupt: 90 million marks in debt.

Even Goebbels, Hitler’s devoted acolyte, admitted in his viciously concise diary that “the year 1932 has been a long streak of bad luck.” It has to be torn to pieces.’

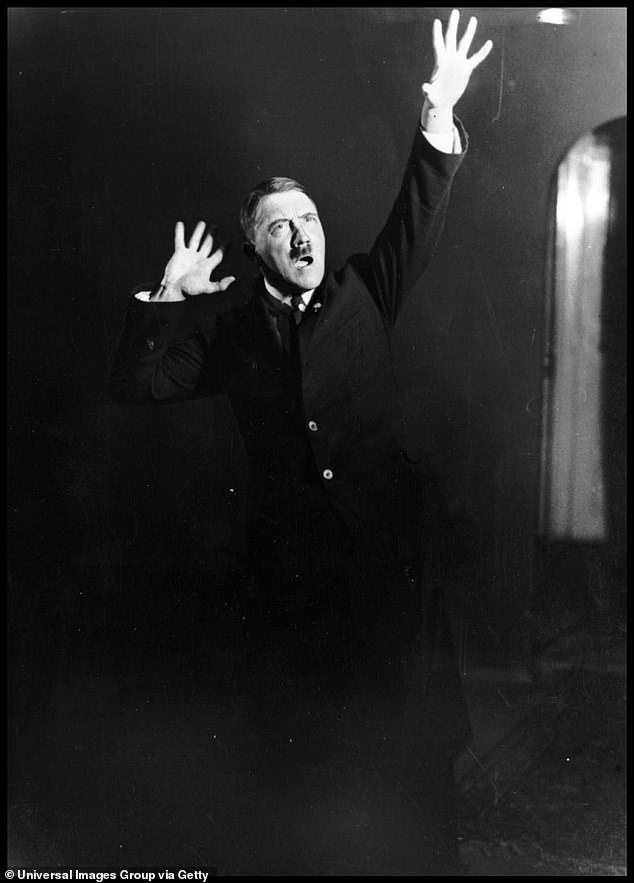

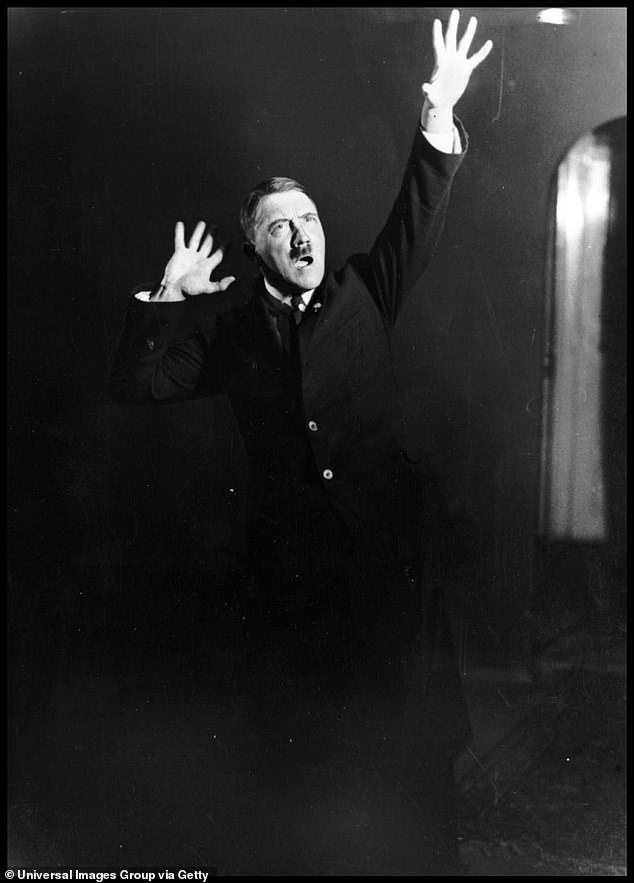

Hitler is hailed by adoring crowds after being appointed chancellor in 1933.

German President Paul von Hindenburg with Chancellor Adolf Hitler after his election victory

However, just six days after that ridiculous caricature, Reich President Field Marshal von Hindenburg would name the little “Bohemian corporal” (as he called him) as his new chancellor. Hindenburg could barely stand it. So how the hell did it happen?

Reading Timothy Ryback’s excellent, forensic account of the complicated events of German politics in the six months leading up to that fateful moment, I found myself wishing that the end result would not happen. I clung to the mistaken opinions of so many commentators of the time: “Hitler is out of the race.” “His reputation is declining.” Even on January 28, 1933, Ryder writes, German newspapers were still predicting a variety of impending coalitions, none of which included Hitler.

But none of those commentators took into account the fundamental fact that we now know to be true: nothing could stop Hitler. Like a toddler throwing a tantrum, he screamed and ranted until he got his way. As tough as steel, setbacks positively revitalized him and, in fact, he played his cards precisely right to get what he wanted: total and dictatorial power.

As he had written in Mein Kampf, recalling his unhappy childhood in Austria, not even his father’s harshest spankings had been able to weaken his resolve. Ryder’s book is a terrifying testimony to the triumph of stubbornness.

“Nein,” Hindenberg said, politely but firmly, to Hitler when this book was opened in August 1932. Hitler had arrived to meet the president, hoping to be named chancellor. Having won 37 percent of the nation’s votes, he insisted that this gave him the right to be the country’s leader.

But Hindenburg told him that he could never entrust the government to a party whose members were so intolerant, undisciplined and violent. Just five days earlier, Hitler’s stormtroopers had broken into the home of communist trade unionist Konrad Pietzuch and murdered him in front of his mother. “But, Herr President of the Reich,” Hitler pleaded, “keep in mind that my people sometimes get a little excited.”

Admitting that the National Socialists were now a party with strong national support, Hindenburg asked Hitler if he would agree to participate in the government. To which Hitler, with equal force, replied: “Nein.” He had no intention of playing second fiddle to anyone.

On quite a few occasions over the next five months, politicians attempted to bribe him or force him to form a coalition government with them. “He would rather besiege a fortress than be a prisoner in one,” was Hitler’s dismissive response.

He insisted that single-party government was the only possible solution to Germany’s innumerable problems. “Dictatorship,” he explained to an American journalist, “is the only viable future for Germany.”

It was true that the German parliamentary system had collapsed in the chaos of too many weak and short-lived coalitions.

Hindenburg increasingly resorted to using his ‘Article 48’ powers to issue dictator-style emergency decrees without parliamentary approval.

At the end of that meeting in August 1932, it was agreed that Hitler would go over to the opposition. The current chancellor, Von Papen, would remain in office. And Hitler promised to make life difficult for both of them. He would paralyze the Reichstag (parliament) and wreak political and social chaos.

This is exactly what he did, hence those new elections in November, in which the Nazis did poorly.

But none of the other parties did well either. Von Papen resigned because he knew he could not bridge partisan divisions and find a way to govern. Apparently, no one could.

Hindenburg appointed Kurt von Schleicher as the new (and ultimately last) chancellor of the Weimar Republic, hoping that he could work with the Nazis to create a viable government. Others fervently hoped that the nationalist business magnate Alfred Hugenberg could form a coalition with the other, slightly more acceptable Nazi, Gregor Strasser. I admit that at the time my head was spinning with every possible political permutation.

By mid-January 1933, constitutional paralysis had occurred. Schleicher became frustrated trying to run the government without a mandate to rule by dictatorial decree. Hindenburg was growing irritated with him and Schleicher, finding himself isolated and in the cold, resigned.

Von Papen, who detested Schleicher, saw his opportunity. He had remained in communication with Hindenburg and suggested forming a new government with Hitler in charge.

“Do you mean to tell me,” said Hindenburg, “that I have the unpleasant task of appointing this Hitler as the next chancellor?” Papen nodded.

Hitler pictured rehearsing a speech in front of the mirror in 1933.

First meeting of the Führer’s cabinet in Berlin, on January 30, 1933, in which Hermann Goering, Vice-Chancellor Franz Von Papen and Economy Minister Alfred Hugenberg participated.

Until the last minute, as they take a Mercedes from their hotel to the Reichstag on January 30, we see Hitler and the power-hungry Hugenberg locked in battle on the stairs, both red with rage, arguing over who was going to be who in The gabinet.

The president resented being kept waiting while the two men fought. Hugenberg only softened and backed down when Hitler promised that after new elections he would listen to all voices and “try to build a large majority.” They went up, entered the president’s office and the agreement was signed. Hitler was the new chancellor. The next day, Hugenberg told a friend, “I just made the biggest mistake of my life.”

You certainly did, Hugenburg, and Hindenburg too. Worn out, they had given way to what Hitler promised would be his “thousand-year Reich.”

Three weeks after the new elections in March 1933, far from “building a large majority,” the Reichstag passed an enabling law establishing Hitler’s government as a dictatorship.

The rest is history.

Purchase: Hitler’s Final Rise to Power by Timothy W. Ryback is now available (Title, £25)