In 2021, one of Australia’s most wanted fugitives walked into a police station and turned himself in after almost 30 years on the run from authorities.

Darko Desic had been living a quiet life as ‘Dougie’ on Sydney’s northern beaches, but his job as a handyman dried up during the Covid pandemic.

In 1992, Desic was serving time for growing marijuana in a northern New South Wales prison when he decided to escape, amid fears for his safety if he was sent back to his homeland, the former Yugoslavia, upon his release.

But the years on the run left him jobless, moneyless, homeless and an “emotionally broken” man.

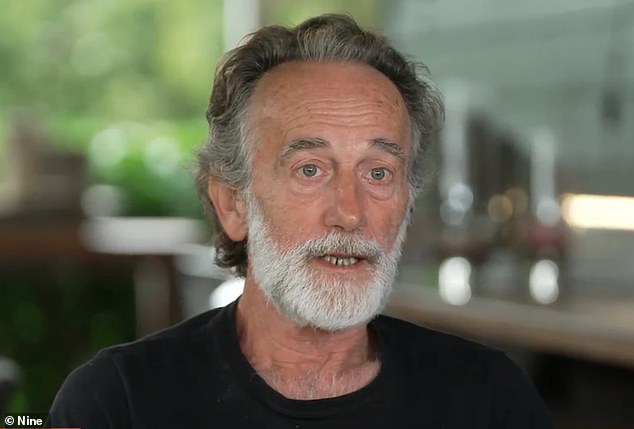

“We reached a point where I no longer had people to trust, like in previous days,” said Desic, now 68 years old. A current issue.

‘I didn’t stay on the beach all the time, I slept on a mattress on a football field. I didn’t feel like continuing anymore. (I thought) that’s it. There is no will and nowhere to go.

Having made up his mind, he entered the Dee Why police station.

“I told him, ‘My name is Darko Desic and I would like to turn myself in. I escaped from Grafton Jail,'” he recalled.

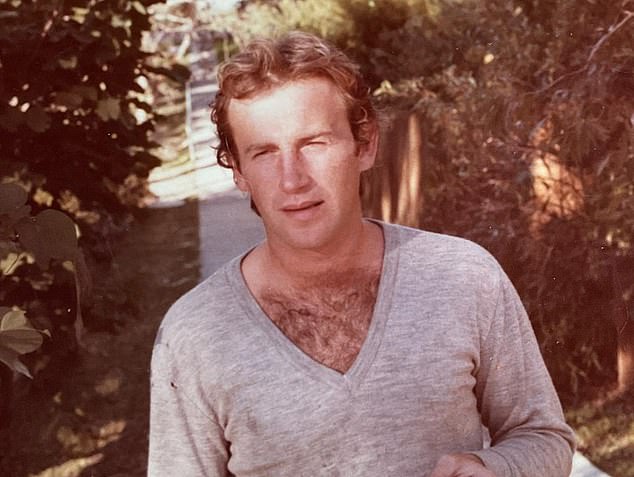

In 2021, 30 years after escaping from prison in New South Wales, one of Australia’s most wanted fugitives, Darko Desic (pictured) walked into a police station and handed himself in.

Darko Desic appears in the photo when he was much younger, before his life of notoriety began.

Desic’s life on the run began in the coastal suburb of Avalon, 38 kilometers north of Sydney’s financial district.

“I lived with surfers, I moved from one place to another, I didn’t have to have identification, no one asked anything,” he said.

The locals didn’t ask the man they called Dougie too many questions, which suited him just fine.

“If there was ever a mention, I think it was once or twice about (being) a legal immigrant,” he said.

He was a qualified engineer, and while he was grateful for the odd jobs he was hired to do, he also wanted to keep his brain busy.

So he taught about computers through books.

“I spent quite a bit of money on books about operating systems, programming languages and computer architecture,” he said.

Desic felt safe in Avalon among his new friends, but he was desperately close when a detective knocked on his door.

“My face must have fallen because he said, ‘Don’t worry, it has nothing to do with you.'”

Although he was free, he always had to be looking over his shoulder, wondering who to trust and what the future held.

“I basically lived like a monk, more or less,” he said.

Then Covid arrived. Although many people lost their jobs, they were able to obtain greater social benefits during the pandemic.

But not Desic. He lost his job and his home and, without access to any government help, made the fateful decision to turn himself in.

He would like to visit Croatia, but above all he wants to become an Australian citizen.

He ended up back behind bars to finish his sentence and served two more months for escaping.

With a roof over his head and three meals a day, he had no intention of trying to escape from prison again.

‘Never. They could have opened the door. “It would never have come out,” he said.

Jail was different the second time too.

‘It was a different generation. Now he was an uncle,’ Desic said with a smile.

However, when his sentence ended, he was immediately transferred to Sydney’s Villawood Detention Center for deportation.

People who knew him on Sydney’s northern beaches, and many who had never met him, put up signs calling for his release and for the government to have mercy on the now elderly man.

‘I was always surprised why. Even today I am surprised by the reason. There’s nothing I’ve done that’s extraordinary,’ he said.

But solicitor Paul McGirr, who took up Desic’s case pro bono, said: “He had served his sentence well and sincerely and had given back to the community without receiving a penny of welfare in any way.”

McGirr said it was a classic Australian tale. It’s a bit of Australian larrikinsim. We were founded on a convict agreement, whether we like it or not.

“At the end of the day, Australians like stories that are a bit dishonest, and we always have.”

Desic finally received the phone call he had been longing for. For the first time in more than three decades, I was truly free. His release certificate is in the photo.

Desic finally received the phone call he had been longing for.

For the first time in more than three decades, I was truly free.

He now lives alone on a farm near Sydney, and a Sydney businessman who supported him from the beginning gave him a job and a house.

But in a way he is still a prisoner, because he cannot prove who he is.

Yugoslavia, the country he left, no longer exists.

Desic tried to get a Croatian passport and got his original Yugoslav birth certificate. But it wasn’t enough.

‘I went to the Croatian consulate. “I don’t have identification documents,” he said.

You need a primary photo ID, such as a driver’s license or photo ID. But Transport NSW told him he can’t get it either because he can’t prove who he is.

He would like to visit Croatia one day, but above all he wants to become an Australian citizen.

‘I feel like an Australian. I don’t speak as such with my accent, but the feeling is different from the way you speak and your accent.’

Desic is eternally grateful to everyone who supported him.

“Their trust in me was valid,” he said.

Desic decided to break his silence because he hopes to “maybe inspire people, to some extent.” To survive.’