A Minnesota goat has tested positive for bird flu, marking the first case of bird flu in domestic livestock in U.S. history.

The kid, which tested positive for the H5N1 strain of highly pathogenic avian influenza, the strain of bird flu that has been spreading since 2022, came from a farm in Stevens County, in the west of the state.

Authorities suspect the goat caught the flu from the infected bird because the animals shared the same space and had access to a common water source.

Dr. Thomas Moore, an infectious disease physician at the University of Kansas, says this marks a “worrying development” because it shows the virus is poised to infect other mammals and even humans.

It is rare for mammals to get bird flu because they have fewer receptors in their upper respiratory tract for the virus to bind to.

The kid, which tested positive for the H5N1 strain of highly pathogenic avian influenza, the strain of bird flu that has been spreading since 2022, came from a farm in Stevens County, in the west of the state.

Authorities suspect the goat caught the flu from the infected bird because the animals shared the same space and had access to a common water source (file image)

All animals have been quarantined and there is an “extremely low” risk to the public, with only those who have had direct contact with the animals being at risk, according to the Minnesota Animal Health Board.

Although there does not appear to be a mutation this time, experts told DailyMail.com that the longer the virus persists undetected in mammals, the more likely it is to mutate.

The farm previously experienced an outbreak of H5N1 among poultry in February, and the birds were quarantined to try to stop the spread.

Health authorities are still investigating how the virus was transmitted and the council said it had quarantined all other species on the farm.

“Fortunately, research to date has shown that mammals appear to be dead-end hosts, meaning they are unlikely to spread HPAI further.”

Animals with weakened immune systems, like kids in this case, are at higher risk of contracting the disease in general.

But Dr Moore told DailyMail.com it was a reminder that at any time bird flu could acquire a mutation that made it transmissible to humans.

He said: “This is obviously a worrying development. Because you don’t know, where does it end? …The virus is constantly replicating and we don’t really know where it will end up.

“I think it’s reasonable to assume that this is the only infected goat.” Especially if you have a documented infection and poultry nearby.

He added: “The fact is that you’re a bit concerned about it is whether it’s transmissible to wild birds in the area who can then carry it. You can apply all the quarantine you want to goats and domestic poultry, but if you suspect wild birds are acting as vectors, it can spread widely.

Dr. Brian Hoefs, state veterinarian, said: “This finding is important because, while spring migration is certainly a higher-risk transmission period for poultry, it highlights the possibility that the virus could infect other animals on multi-species farms.”

No one has become ill after coming into contact with mammals infected with bird flu.

In August 2023, tthere are people in Michigan have been diagnosed with pigs flu after being exposed to infected pigs at county fairs.

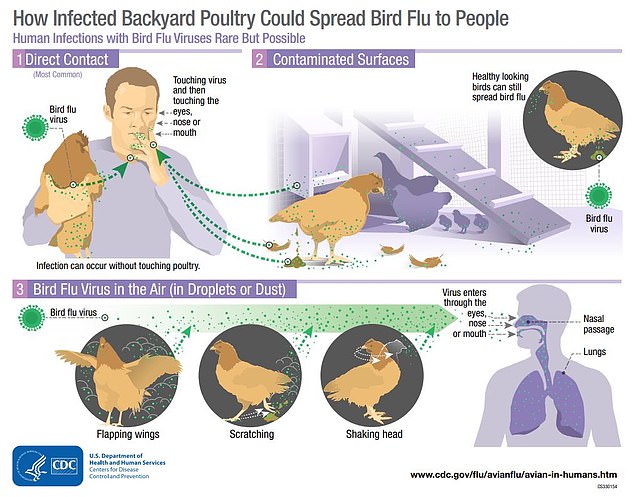

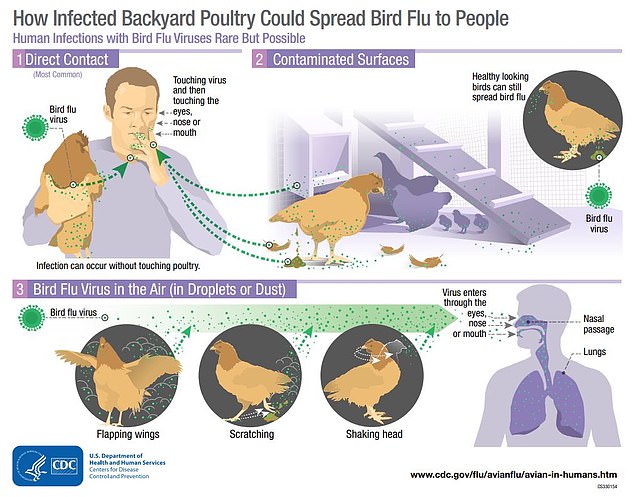

Like all flus, the virus is spread primarily by droplets in the air that are inhaled or enter a person’s mouth, eyes, or nose.

The current avian flu outbreak has been raging for almost two years, affecting every corner of the world, including Antarctica, for the first time.

Experts have warned that the increase in cases in mammals could lead to a recombination event, when two viruses, such as avian flu and seasonal flu, change genetic material to create a new hybrid.

A similar process is believed to have caused the global swine flu crisis in 2009, which infected millions of people across the planet.

For decades, scientists have warned that avian flu is the most likely candidate for triggering the next pandemic.

This could see a deadly strain of bird flu merge with a transmissible seasonal flu.

In the United Kingdom, a December report showed that four samples from infected otters and foxes “showed the presence of a mutation associated with potential benefits for mammalian infection.”

The UKHSA warned that “the rapid and consistent acquisition of the mutation in mammals may imply that this virus has a propensity to cause zoonotic infections”, meaning it could potentially spread to humans.

Yuko Sato, a veterinarian and poultry extension diagnostician at Iowa State University, told DailyMail.com that there appears to be no mutation between the virus received from the goat and that received from the chicken.

“Fortunately, it appears to be just horizontal diffusion,” she said.

But she added: “The biggest risk is probably just that the virus is present in different groups of animals without being detected.

“The longer the virus is around, the more capacity it has to mutate.” As soon as there’s something wrong, I think it was great that (Minnesota farmers) diagnosed it very quickly and investigated it, because the longer it persists, the more there will be of problems.

As for whether that increases the risk of human spread, she said: “I don’t know yet. But this virus appears to be more likely to have that potential than the previous virus from 2015.”

The last case of avian flu in a commercial bird colony in America was in June 2015.

An outbreak of avian flu occurred between December 2014 and June 2015, with more than 200 cases of avian flu among backyard poultry and wild birds.

Avian flu has led to the culling of five million birds in the United States in 2023 in an attempt to prevent an outbreak.

Last year, Dr Sylvie Briand, Director of Epidemic and Pandemic Preparedness and Prevention at WHO, said: “The global H5N1 situation is worrying given the wide spread of the virus among birds in the world and the increase in reported cases in mammals, including humans. ‘

H5N1 was first detected in chickens in Scotland in 1959, and again in China and Hong Kong in 1996. It was first detected in humans in 1997.

Human-to-human transmission of H5N1 is incredibly rare, but not impossible. In 1997, authorities confirmed 18 cases of H5N1 in Hong Kong, some of which were due to human-to-human transmission. The epidemic, however, remained relatively limited. And it has not escalated into a major problem, either locally or globally.

This recent epidemic has caused particular concern. More than 15 million domestic birds and countless wild animals have been struck down by the virus.

There is nothing that can be done to prevent the spread among wild birds, but authorities are working to keep domestic populations away. In the UK, all farmed chickens must now remain indoors.