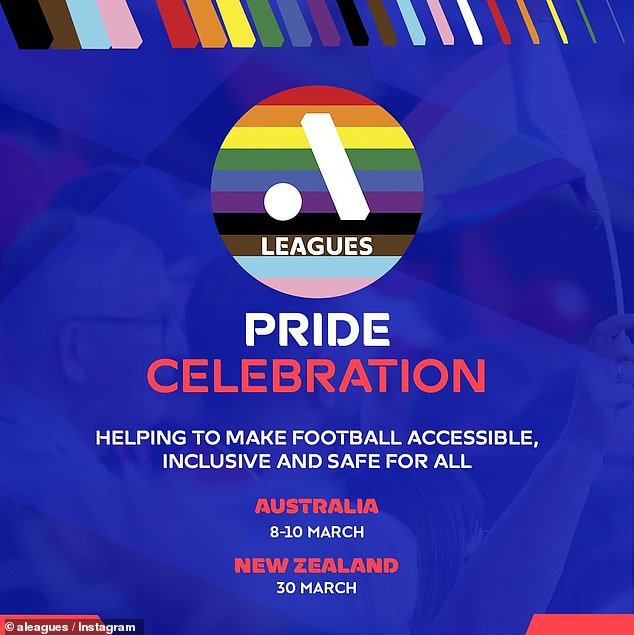

- Pride celebration will take place in March

- A-Leagues pride themselves on embracing diversity

- Some football fans disagree

Countless football fans across Australia are furious following the A-Leagues’ announcement that the Pride Celebration will be reintroduced this season.

In a bid to celebrate inclusivity, the Australian Professional Leagues (APL) have set aside March 8-10 in Australia and March 30 in New Zealand as dates for their fans to embrace sexual diversity.

It follows the A-Leagues in 2023, becoming the first competition in the world to hold men’s and women’s Pride celebrations simultaneously.

A-Leagues Commissioner Nick Garcia called the Pride Celebration another example of how “welcoming and inclusive football is as a sport for everyone in Australia and New Zealand.”

Central Coast Mariners women’s captain Taren King was on the same page and can’t wait for the round to be held widely.

Countless football fans across Australia are up in arms following the A-Leagues’ announcement that the Pride Celebration will take place again this season.

Central Coast Mariners captain Taren King can’t wait for round to be widely celebrated

In 2021, Adelaide United defender Josh Cavallo confirmed that he was gay, as he was fed up with “leading a double life”.

‘I’m very excited for this season’s Pride round. “Last year we saw several clubs make a big effort to show their support for the LGBTQI+ community and I’m looking forward to seeing more clubs take up the initiative this season,” he stated.

“I think it is very important that both clubs and players use their platforms to show our fans that everyone has a place in our game and that all individuals are accepted as they are.”

However, the reaction was very different from fans on social media, who want action to be taken to correct declining attendance and alarming drops in revenue.

One posted on

A third fan chimed in: “Our wonderful match in Australia is a complete disaster and this (brain fart of an idea) won’t help.”

“You should try to gain fans, not lose them.”

2GB radio host Chris O’Keefe on Friday criticized the Australian Football body for its mismanagement of funds in recent years.

‘How have the A-Leagues burned $140 million in less than three years?’ he asked.

It comes after the recent Fairfax report revealed that almost half of the workforce behind the A-Leagues were set to be made redundant.

Additionally, the A-Leagues’ media division, KEEPUP, which is said to have cost at least $30 million to establish and maintain, has collapsed and will close on March 1.

Adelaide United, featuring openly gay star Josh Cavello, and Melbourne Victory will headline the A-Leagues Pride celebration on local shores on March 9.

Coopers Stadium will host the annual Pride Cup, with the women’s match (5pm) as part of a double-header before the men’s match at 7.45pm.