The first drug proven to slow Alzheimer’s disease is being denied to dementia patients unless they pay for a private drug.

Regulators yesterday made two landmark decisions: licensing lecanemab in the UK, but then refusing to give it to NHS patients on cost grounds.

This means those who are eligible in England can only access the drug, which slows cognitive decline by up to six months, if they can afford to pay tens of thousands of pounds a year for private treatment.

Last night, charities warned that the conflicting rulings will cause “uncertainty and confusion” for up to a million dementia sufferers and their families desperate to access treatments.

David Thomas, of Alzheimer’s Research UK, said the decisions meant the “revolutionary” drug would likely be out of reach of “all but the wealthiest individuals”.

Lecanemab (pictured) has been shown to slow the progression of the memory-destroying disease in its early stages. It has been approved today by the drug regulator, the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA).

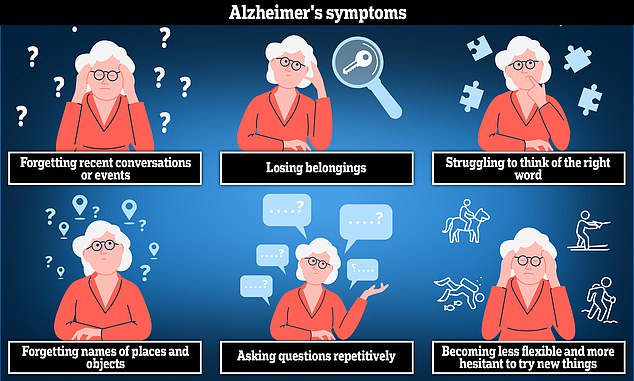

Alzheimer’s disease is the most common cause of dementia. The disease can cause anxiety, confusion and short-term memory loss.

He said: ‘There are people who could benefit from this drug on the NHS right now.

“If there is an authorised medicine that is safe and effective, in the opinion of the regulator, then it should be available to NHS patients, and not just those who can afford to pay.”

He added: “This drug is not a silver bullet, but we should be thinking about how the UK can take advantage of it rather than not providing any access and letting other countries do the legwork – it doesn’t seem right.”

“We have the capacity to provide medicines by infusion on the NHS (this is done in cancer and other disease areas) and we now have the appropriate diagnostics available.”

The annual cost of dementia to the economy is estimated at £42 billion, with lost income and unpaid carer costs dwarfing the costs of treatment. Earlier this year, the Alzheimer’s Society predicted these costs would reach £90 billion over the next 15 years, with families bearing the brunt of providing unpaid care.

But these external costs are not taken into account by regulators, whose role is to assess value for money against other NHS treatments.

The trials found that lecanemab slowed cognitive decline by about a quarter in patients with early Alzheimer’s, leading many to call it a “turning point” in the fight against the disease.

It received the green light from the Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency, the body that decides whether a drug works and is safe.

But the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (Nice) simultaneously announced that the benefits of lecanemab were “too small to justify the significant cost to the NHS”.

Around 70,000 NHS patients in England would have been eligible for it, with an estimated cost of around £30,000 a year per patient to buy and administer it.

But Nice said the cost of biweekly infusions in the hospital, intensive monitoring for rare but serious side effects and the “relatively small benefits it provides to patients” do not offer good value for the taxpayer.

Vanessa Raymont, an honorary consultant psychiatrist at the University of Oxford, said the MHRA’s approval of lecanemab was “groundbreaking”.

He said it was the first drug approved in the UK with “the potential to… have a real impact on the progression of memory decline”.

It is being used in the US and Japan, but the EU regulator has rejected it because of the risk of serious side effects. In their submission to the regulator, the manufacturers presented estimates of the “non-medical” costs of the care.

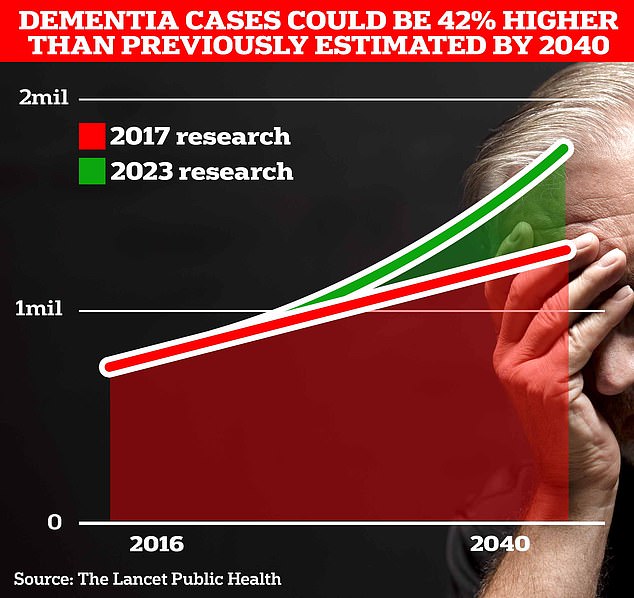

Around 900,000 Britons are currently thought to have the memory-impairing disorder. But scientists at University College London estimate this figure will rise to 1.7 million within two decades as people live longer. This is a 40% increase on the previous forecast in 2017.

The price of the drug has not been publicly announced in the UK. In the US, the treatment costs £20,000 a year, but last month the European Medicines Authority (EMA) rejected it due to concerns about side effects such as “swelling” and “possible bleeding in the brain”.

But the Nice committee, according to the Telegraph, excluded the evidence on the grounds that most of the care had been paid for by families or was provided by them without pay.

Mr Thomas, from Alzheimer’s Research, said: “The failure to include the cost of care in the model is fundamentally unfair. The way these assessments are carried out is simply not fit for purpose.”

Nearly a million people in the UK are living with dementia. Experts said that despite yesterday’s setback, “it is a question of when, not if, new treatments will become available” with more than 160 trials underway around the world.

A Department of Health spokesman said: “It is right that these decisions are made independently. The Government is committed to furthering research and innovation in this area.”