Jimmy Carter was so confident in his unlikely path to the White House that he bet that Americans worn down by Vietnam and Watergate would welcome a new kind of president: a peanut farmer who carried his own suitcases, worried about the heating bill. and told him, more or less, how it was. And for a time, voters welcomed it.

Yet just four years later, after a presidency many considered a failed one, it sometimes seemed as if all that was left of Carter was the smile: the wide, toothy smile that helped elect him in the first place, and then came. being caricatured by countless cartoonists as an emblem of naivety.

But it was Carter’s great fortune to enjoy a post-presidency more than 10 times longer than his term (in March 2019, he became the oldest president in history) and when he died at age 100., he had lived to see the verdict of history softened.

Carter was admitted to home palliative care after a series of hospital stays, the Carter Center confirmed on February 18. His wife, Rosalynn Carter, passed away on November 19, 2023.

yes 39 th The president did not achieve everything he sought in four years in the White House (and he did not); his constant concern for human rights in international affairs, and for energy and the environment as a decisive challenge of our time, can now be considered prophetic. . If, in later years, his unwavering support for Palestinian rights (and his frequent harsh criticism of Israel) attracted many detractors, his brokering of the 1978 Camp David Accords between Israel and Egypt constitutes a milestone of modern diplomacy.

If he was the first president to confront what we now call “Islamic extremism,” he was far from the last. And if he sacrificed his re-election to the superimpotence of the Iranian hostage crisis (and a failed military raid to rescue the captives), his administration’s persistence ultimately saw the 52 diplomats return home safely.

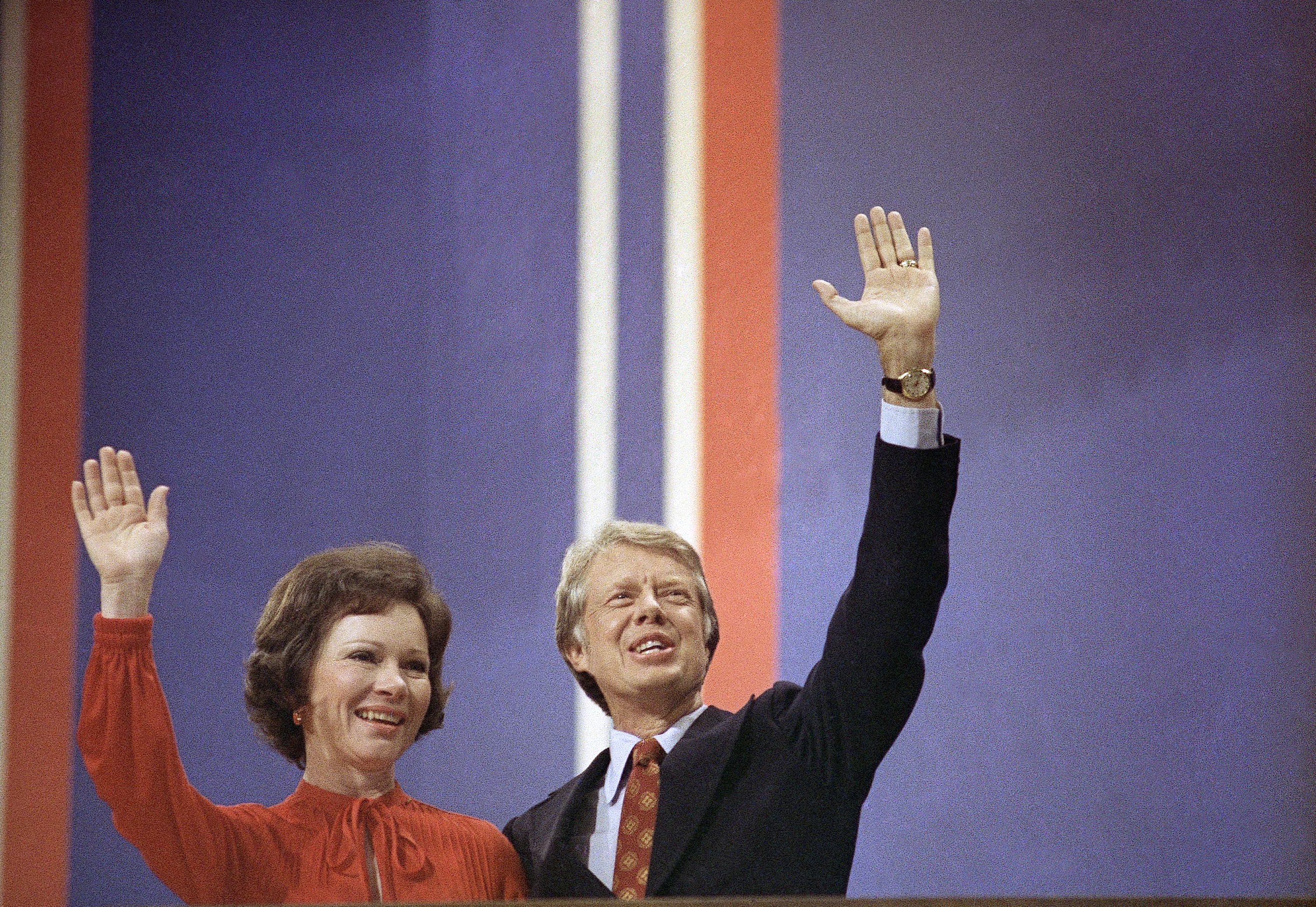

At a time when only six women had served in a president’s Cabinet, Carter had appointed three of them, along with three of the five women who had once served as departmental undersecretaries and 80 percent of them to serve as undersecretaries. There is almost no policy or public image battle that Hillary Clinton or Michelle Obama faced as first lady that Carter’s trusted wife, Rosalynn, didn’t fight first, whether campaigning for mental health or participating in Cabinet meetings. .

James Earl Carter Jr. could be pious (“I will never lie to you,” he promised during his 1976 campaign). He could be petty (his micromanagement of the White House tennis court was roundly mocked). He could be tone-deaf (lecturing his countrymen about a national “crisis of confidence” in a way that only accentuated the problem, and dispensing with some of the pageantry of the presidency that ordinary people really liked and expected).

But he could also be incredibly sincere, in a political culture that almost never rewards that trait (who can forget his confession to Playboy magazine that he had lusted after women, not his wife, and that he had committed adultery many times in his heart). ?). a gift for unlikely friendships, especially with the man he defeated so narrowly and bitterly, Gerald Ford, and with John Wayne, the ultraconservative whose support nevertheless helped him approve the 1977 treaty handing over the Canal. Panama.

He grew up in a house with no indoor plumbing, on a dirt road in rural Georgia, surrounded by poor blacks, and was the only president to ever live in public housing (when he got out of the Navy, when he returned home to get He took over his family peanut business after his father’s death. He was the son of a staunch segregationist and early in his career, until his election as governor of Georgia in 1970, he often honed in on race. in the Chamber of Representatives proclaimed that “the time of discrimination is over” and Time magazine hailed him on its cover as the face of America’s New South.

Carter’s life had a classic Horatio Alger arc. As a teenager, he joined Future Farmers of America and grew, packaged and sold his own acre of peanuts. He fulfilled his dream of being appointed to the United States Naval Academy in Annapolis and became a protégé of Hyman Rickover, the father of the nuclear Navy, in the post-World War II submarine fleet. He married a childhood friend of his sister Ruth and had four children.

His first political position was the quintessential American position: president of his local school board, where in the early 1960s he first spoke in favor of integration. Two terms in the Georgia State Senate and an unsuccessful run for governor in 1966 paved the way for his election as governor in 1970. By late 1972, he was determined to launch a presidential campaign, but the long odds against him were exemplified. . in a 1973 appearance on “What’s My Line,” where none of the celebrity panelists recognized him and only film critic Gene Shalit ultimately guessed that he was governor.

But Carter’s status as an unknown outsider was a clear advantage after Watergate – an advantage that the late RW Apple Jr. of The New York Times understood early – and he quickly became the favorite for the Democratic nomination, winning the election. Iowa caucuses and New Hampshire primaries. In 1976, he published his campaign manifesto-memoir, confidently titled “Why Not the Better?” and the rest is history.

At his inauguration, Carter brought a cool, bracing breeze to Washington, walking from the Capitol to the White House after his swearing-in. But soon he also adopted a stern, scolding tone, ordering that the White House thermostats be set to a frigid 65 degrees (a move he ostentatiously announced in a televised “fireside chat,” wearing a bright-colored cardigan. cinnamon), selling the yacht presidency Redwoodbanning strong alcoholic beverages at White House parties and limiting the performance of “Hail to the Chief” at official events.

Much of the national media and Washington’s chattering class quickly declared the new president a boor, out of his depth and surrounded by an equally uneducated and boorish “Georgia mob.” He responded with stinging disdain to his critics. The same style that had seemed modest and refreshing now seemed prudish and moody, and in essence, couldn’t seem to catch a break. He was saddled with a national economy trapped in “stagflation,” and in June 1978, Stephen Hess of the Brookings Institution was analyzing why his presidency had failed: because it lacked an overarching vision.

In an afterword of excerpts from his White House diaries, published in 2010, Carter would write: “As is clear from my diary, I felt at that time that I had a firm grip on my presidential duties and was presenting a clear picture of what He wanted to succeed in internal and external affairs. The three big themes of my presidency were peace, human rights and the environment (which included energy conservation).” But he added: “However, in retrospect, my elaboration of these issues and my departures from them were not as clear to others as they were to me and my White House staff.”

In 1980, Carter faced a challenge for a new nomination from Senator Ted Kennedy, and then lost the November election to his polar opposite, Ronald Reagan. He was in a bad mood for a while, then bought a $10,000 Lanier word processor, composed the first of the more than two dozen books he would write upon leaving office, and set about establishing his presidential library and the Carter Center in partnership. with Emory University in Atlanta.

Over the following decades, he would build Habitat for Humanity homes, oversee foreign elections, conduct semi-sanctioned (and sometimes unsolicited) diplomacy, and continue to offer various unvarnished assessments of his successors from both parties. When posing in the Oval Office in 2009 with all the living members of the presidential club, shortly after the election of Barack Obama, he could not help but leave a notable physical distance between himself and his southern colleague Bill Clinton, an old enemy whose extramarital affair during The mandate so offended Carter, long the country’s chief Sunday school teacher. (He continued to live out his role: Carter continued teaching Sunday school in Georgia year after year, and later took pictures with everyone who attended.)

Most surveys of professional historians still place Carter in the third quartile of effective presidents (as it happens, on par with his friend Jerry Ford). Carter himself preferred the simple summary of his vice president, Walter Mondale: “We obeyed the law, we told the truth and we kept the peace.”

In the long presidential career, that is not the best boast ever seen. But it’s far from the worst.