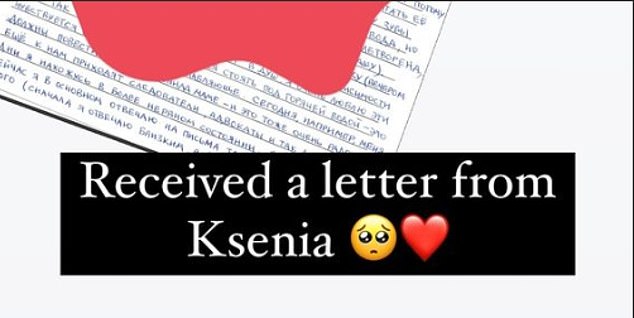

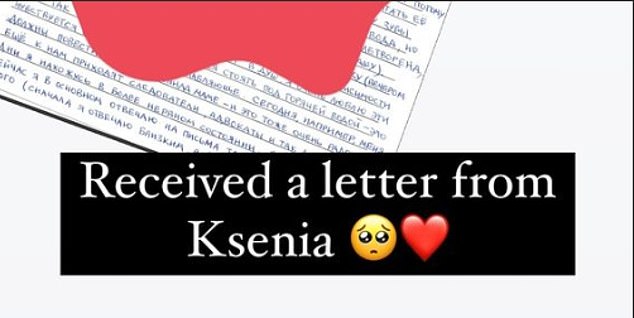

Los Angeles dancer Ksenia Karelina’s boyfriend received a “love letter” from the Russian prison where she is awaiting trial for high treason after donating $50 to a Ukrainian charity.

Boxer Chris Van Heerden revealed he had been planning to propose to the 33-year-old woman before she was arrested and taken blindfolded to a Russian court while visiting her elderly grandparents in January.

His girlfriend is now detained in a cell 1,000 miles east of Moscow in conditions that contrast with her job as a beautician at a spa in Beverly Hills.

“They have to go to bed at 10 and shower once a week, which is painful,” said Van Heerden, 36.

“She said, ‘I have a little window in my cell and I can see the sun, and I know I’m looking at the same sun that you look at when the sun goes down.'”

Chris Van Heerden said Karelina had sent him a “love letter” from her Russian prison cell detailing the terrible conditions in which she is being held.

Karelina is accused of raising funds for a pro-Ukrainian organization; she obtained US citizenship in 2021

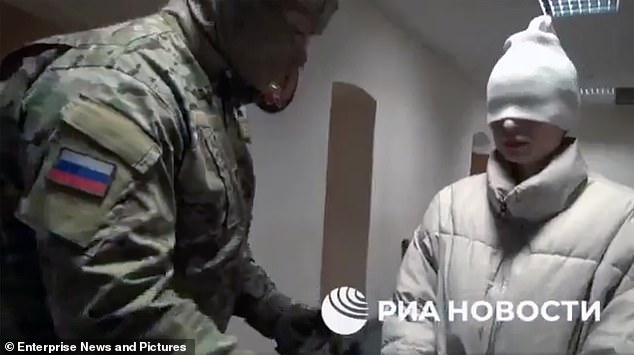

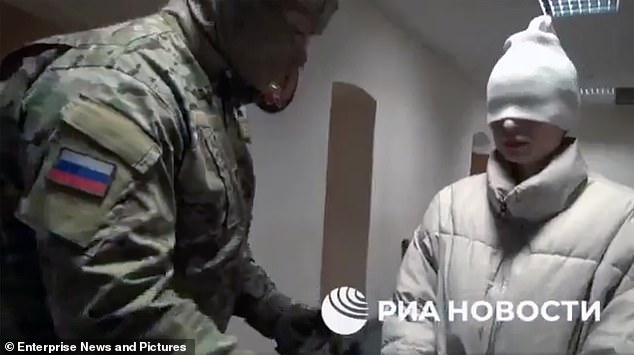

Images of Karelina chained and hooded shocked the world when she was photographed being taken to a Russian court accused of high treason.

Karelina, who has dual Russian-American citizenship, faces up to 20 years in prison for making a small donation to the humanitarian charity Razom on the day Russia invaded Ukraine.

The payment was discovered after his phone was confiscated when he flew into Yekaterinburg’s Koltsovo airport on January 2, planning to visit his 90-year-old grandparents in time for Christmas Day in Russia.

She was arrested after being invited to pick up her phone on January 27, the day Ven Heerden last spoke to her.

“Fifty-one dollars, come on,” he told NBC, “a simple donation because she’s nice.”

‘I was actually thinking about proposing to this woman, so every day is hard.

‘He has an affectionate smile. Always happy, so, so, so generous. Live a full life.’

A detention hearing this week denied her request to be held under house arrest and Russia has refused to grant consular access to US officials as Karelina becomes the latest pawn in a diplomatic war between Washington and Moscow.

“I had no illusions,” Van Heerden said, insisting he would need a “miracle” to escape Russian custody.

Los Angeles dancer and beautician faces up to 20 years in prison if convicted

Ksenia Karelina, 33, a dual Russian-American citizen, was arrested by Vladimir Putin’s Federal Security Service, the FSB, on January 27.

Ksenia Karelina, 33, pictured with her father Pavel, mother Liliya and younger sister, remains detained in Russia on charges of high treason.

The case has further fueled fears that Western citizens with Russian passports are being targeted for arrest in Russia.

On her Facebook page, Karelina says she is from Yekaterinburg and studied ballet at the SP Diaghilev school.

“I broke down because I know Ksenia, she is a sweetheart, she is very soft and I can’t imagine how scared she must be,” she added.

‘I want people to know that Ksenia is a normal person, that’s my job. She is a normal American citizen who made a mistake.

‘I’m in a fight right now totally out of my control, I’m in a fight that I’m not familiar with. “I’m trying my best to do everything I can.”

Yekaterinburg is also the same city where Wall Street Journal journalist Evan Gershkovich was arrested on espionage charges almost 12 months ago.

Karelina was sentenced to 14 days of detention for “petty hooliganism” before being charged with treason.

Russia’s FSB claims that it “proactively raised funds in the interests of one of the Ukrainian organizations, which the Ukrainian Armed Forces subsequently used to purchase tactical medicines, equipment, weapons and ammunition.”

In a statement, Razom CEO Dora Chomiak said the organization is “shocked by Karelina’s arrest.”

“Vladimir Putin has repeatedly demonstrated that he does not consider any sovereign border, foreign nationality or international treaty above his own interests,” Chomiak said.

“His regime attacks civil society activists who defend freedom and democracy.”

Last week, Karelina’s distraught father said he didn’t know how to help her.

Speaking publicly for the first time in an interview with DailyMail.com, Pavel Karelina, 56, said he could not comment on the Russian government’s ongoing case against his daughter, but thanked the public for their support.

‘We can’t really say anything now. We ourselves do not understand what is happening,” said Pavel, general director of a Russian transport equipment company.

‘Please understand. Thanks for your good wishes.’

Karelina’s ex-husband, Evgeny Khavana, revealed last month that his own family lives in fear and cannot speak freely because he believes Russian authorities are “listening to” them.

He said: “We can’t talk, my family can’t say anything,” he added.

Her mother-in-law, Eleanora Sreboski, told DailyMail.com that Ksenia would spend the rest of her life in a Russian prison if the United States did not intervene.

Van Heerden said his girlfriend wavered between motivation one day and hopelessness the next, but was “prepared for what could be the fight of her life.”

She said guards let her out of her cell once a day, but sometimes kept her outside for hours in the frigid Russian winter.

Karelina was still dancing in the last video call between the couple before her arrest.

The South African-born former IBO welterweight champion says he is now in a “fight I’m not familiar with” as he fights to free his girlfriend.

“Ksenia is a sweetheart, she’s very soft and I can’t imagine how scared she must be,” he said.

“I’m in a fight right now totally out of my control, I’m in a fight that I’m not familiar with,” he added.

‘I’m doing my best to do everything I can.

‘I want people to know that Ksenia is a normal person, that’s my job. She is a normal American citizen who made a mistake.

“Ksenia is a sweetheart, she’s so soft and I can’t imagine how scared she must be.”